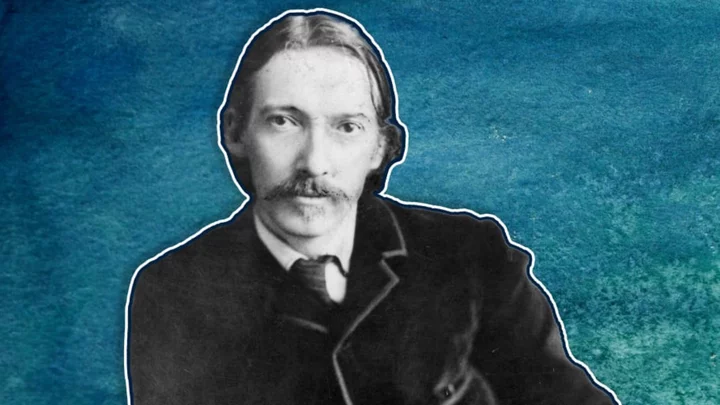

Along with Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson is one of Scotland’s foremost writers. His most popular novels—the swashbuckling Treasure Island and the Gothic Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—cemented his place among the literary greats. A 2018 analysis revealed that he is the seventh most adapted author in the world, and according to UNESCO, he is also the 26th most translated author. Here are a few facts about Robert Louis Stevenson—whose life, like his most famous stories, was full of both adventure and misfortune.

1. Robert Louis Stevenson suffered from lifelong chronic lung illnesses.

Robert Louis Stevenson was born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson in Edinburgh, Scotland, on November 13, 1850 (he got rid of Balfour and changed Lewis to Louis when he was a young adult). He inherited a susceptibility to respiratory problems from his mother, Margaret Isabella Balfour, and throughout his life was plagued with chest infections that left him thin and frail. His symptoms were characteristic of tuberculosis—he had a bad cough, fever, and difficulty breathing, and spat up blood—but there were no tests for the condition at the time, so some experts have suggested that he may have suffered from a rarer disease with similar symptoms, like bronchiectasis or Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome.

Stevenson’s ill health meant that he was in and out of formal education as a child, and he was taught by private tutors during particularly bad bouts of sickness. During this time he grew particularly close to his nurse Allison Cunningham, known as “Cummy.” According to the Robert Louis Stevenson Museum, “Cummy would regularly read to him from the Old Testament, Catechisms, and Bunyan’s [The Pilgrim's Progress]. This somewhat isolated childhood led to the development of a healthy imagination through which dreams of being a writer developed.”

2. Stevenson’s family expected him to become a lighthouse designer.

Stevenson came from a family of engineers who had designed the majority of Scotland’s lighthouses, and he was expected to join the family business. In 1867, he began studying engineering at the University of Edinburgh—but he had no enthusiasm for the subject, later writing that “I had already my own private determination to be an author.”

He told his parents in 1871, but together they agreed that he would return to university to study law in case he couldn’t support himself financially as an author. Stevenson completed his degree in 1875, but had no intention of practicing law.

Although Stevenson chose literature over lighthouses, his travels around Scotland with his father Thomas to inspect the structures may have provided inspiration for his writing. It has been suggested that Treasure Island’s Skeleton Island was either based off of Fidra in the Firth of Forth or Unst in the Shetland Islands.

3. His literary career began with essays, travel writing, and short stories.

Technically, Stevenson’s first published book, The Pentland Rising (1866), was historical non-fiction. Stevenson was just a teenager when his father paid for the printing of 100 copies of the slim volume. (His father then also purchased almost every copy because he feared that people would criticize it.)

As an adult, Stevenson’s first published works were personal essays—the first, “An Old Scotch Gardener,” appeared in Edinburgh University Magazine in 1871—short stories, and literary and historical essays. His first full-length books were travelogues: An Inland Voyage, which detailed his canoe trip down the Oise River in Belgium and France, hit shelves in 1878; Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, which describes his hike in France with a stubborn donkey named Modestine, was published a year later.

4. Stevenson (sort of) wrote Outlander’s opening credits song.

In addition to novels, short stories, and travelogues, Stevenson also wrote poetry, plays, and music. One of his most famous songs is “The Skye Boat Song,” a traditional Scottish folk tune for which he wrote new lyrics.

The song was originally composed in the late 18th century by William Ross and titled “Cuachag nan Craobh” (“The Cuckoo in the Grove”). A century later, Sir Harold Boulton wrote new lyrics that described the escape of Bonnie Prince Charlie to the Isle of Skye after being defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. Stevenson thought that Boulton’s lyrics were “unworthy,” his wife once explained, and so he wrote his own on the same subject, which were “more in harmony with the plaintive tune.”

Stevenson’s version plays over the opening credits for the TV adaptation of Outlander; Bear McCreary composes different versions of the song for each season. Stevenson’s words are used almost exactly—the only change is “lad” (which refers to Bonnie Prince Charlie) to “lass” (which refers to main character Claire).

5. Stevenson fell in love with a married older woman and embarked on a near-fatal transatlantic journey to marry her.

While in France in 1876, Stevenson met and fell in love with Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne, an American who was a decade his senior and married (although estranged from her husband) with children. She returned to California in 1878, and one year later Stevenson set off from Greenock, near Glasgow, on an arduous journey to marry her.

Stevenson’s experience of traveling across the Atlantic by ship and America by train led to two travelogues, 1892’s Across the Plains and The Amateur Emigrant, posthumously published in 1895. Although the journey was creatively enriching, his transportation’s unhygienic conditions led to a deterioration of his already fragile health. His second class accommodation aboard the ship—one level up from steerage—was cramped, fetid, and dirty, and he found the train to be similar. “I am told I looked like a man at death’s door,” he wrote in Across the Plains, “so much had this long journey shaken me.”

Soon after arriving in Monterey, where Fanny was staying, Stevenson decided to go camping in the hope that the fresh air would restore his health while he waited for her to get divorced. But he fell gravely ill while at a goat ranch in the Carmel Valley. He was rescued by the farmers and then moved to a house—now a Robert Louis Stevenson museum—in Monterey to fully recuperate. When Fanny relocated back to her home in Oakland not long after, Stevenson moved to San Francisco, before another bought of illness drove him into Fanny’s care. Stevenson later described himself on their wedding day, May 19, 1880, as “a mere complication of cough and bones.”

6. Due to his ill health, Stevenson sought out warmer climates and eventually settled in Samoa.

Stevenson, Fanny, and Fanny’s son, Lloyd, spent most of the 1880s chasing warm weather and clean air across Europe to ease Stevenson’s respiratory problems. It was during these years that the author wrote his most popular novels, sometimes while taking medicinal cocaine. After briefly living in America again, the family embarked on an extended South Seas sailing excursion in 1888, visiting places such as French Polynesia and Hawaii (where they befriended King Kalākaua).

As 1889 was drawing to a close, they decided to settle in Samoa (although they sailed to places like Australia and New Zealand while their house was being built). Stevenson was given the name Tusitala (“the teller of tales”) and learned Samoan, even initially publishing “The Bottle Imp” (1891) in the language. Vailima, the Stevensons’ home on Upolu (the second largest Samoan island), has now been turned into a museum.

7. Stevenson wrote against colonization in Samoa.

Living in Samoa had a huge influence on Stevenson’s literary output, causing him to turn his pen to anti-imperialist commentary in A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa (1892), the fictional novellas The Beach of Falesá (serialized in 1892 as Uma) and The Ebb Tide (1894), as well as in several letters to the Times in London. “I see that romantic surroundings are the worst surroundings possible for a romantic writer,” fellow author Oscar Wilde harshly declared—butaccording to scholar Anna Faktorovich, “Stevenson’s history of Samoa was a significant historical reference and theoretical work for later anticolonial writers” who “can frequently be quoted as having learned from and admired some of Stevenson’s works.”

8. Stevenson died at the age of 44—but it wasn’t because of his damaged lungs.

Just a few years after putting roots down in Samoa, Stevenson died—but surprisingly, his failing lungs weren’t the culprit. On December 3, 1894, Stevenson was helping Fanny make mayonnaise for dinner. “I began to mix the mayonnaise; he dropping the oil with a steady hand, drop by drop,” Fanny wrote in a letter to a friend. “Suddenly, he set down the bottle, knelt by the table, leaning his head against it.” The 44-year-old author had suffered a brain hemorrhage and died a few hours later.

Stevenson was buried near the summit of Mount Vaea; the epitaph on his grave is one of his own poems, “Requiem.”

9. RLS Day celebrates the author on his birthday each year …

RLS Day was created in 2011 to celebrate the Scottish author. Each year on November 13 (and the surrounding days), a variety of events—including talks by experts, walking tours, the donning of his characteristic mustache, and pirate-themed treasure hunts—are hosted in Stevenson’s hometown of Edinburgh. Of course, Stevenson’s life and legacy had been celebrated long before the creation of RLS Day. In 1994, for example, a commemorative £1 note that featured an image of Stevenson was released to mark the centenary of his death.

10. … But he actually gave his birthday away.

Three years before he died, Stevenson gave his birthday to a 12-year-old girl. Annie Ide, who moved to Samoa when her father was appointed presidential commissioner, was born on December 25 and understandably resented Christmas Day for stealing her spotlight. Stevenson decided to give Annie his November 13 birthday, even creating a faux legal document to outline the terms. It stated that he transferred all of his birthday privileges to her, including the “eating of rich meats and receipt of gifts.”

This article was originally published on www.mentalfloss.com as 10 Fascinating Facts About Robert Louis Stevenson.