African leaders called for wide-ranging debt relief and a flood of climate finance to help the continent boost its electricity generation from renewable sources almost sixfold by 2030.

In a declaration signed by leaders at the inaugural Africa Climate Summit in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, they called for the tenor of sovereign loans to be extended, debt pauses when climate disasters strike and a 10-year grace period on interest payments. Those measures would go some way to allowing some of the world’s most vulnerable countries to bolster their climate resilience and develop their economies, according to the document.

The declaration, the leaders said, will serve as a basis for the continent’s common position going into the United Nations’ global climate summit, COP28, in Dubai later this year.

There is need “for a comprehensive and systemic response to the incipient debt crisis outside of default frameworks to create the fiscal space that all developing countries need to finance development and climate action,” the leaders said in the so-called Nairobi Declaration on Wednesday.

Africa, the world’s least developed continent, has barely contributed to the greenhouse gas emissions that are driving climate change, but its nations are among the hardest hit by cyclones, droughts and floods. That, coupled with a debt burden exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, is hindering economic growth.

“We are aware of the unjust configuration of multilateral institutional frameworks that perpetually place African nations on the back-foot,” Kenyan President William Ruto said in a closing speech to delegates. “As a continent, we have developed our common position which encapsulates our ambitions for socioeconomic transformation and our climate action agenda.”

Earlier, Ruto said that climate finance pledges of $23 billion had been made at the conference. Fifteen African heads of state attended, according to information from the organizers. Antonio Guterres, the United Nations’ secretary-general, and Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, were also present.

In addition to the declaration, the African leaders called for global taxes on financial transactions and carbon emissions to fund climate resilience projects as well as stressing that more tax from operations on the continent should go to its governments, rather than be paid elsewhere.

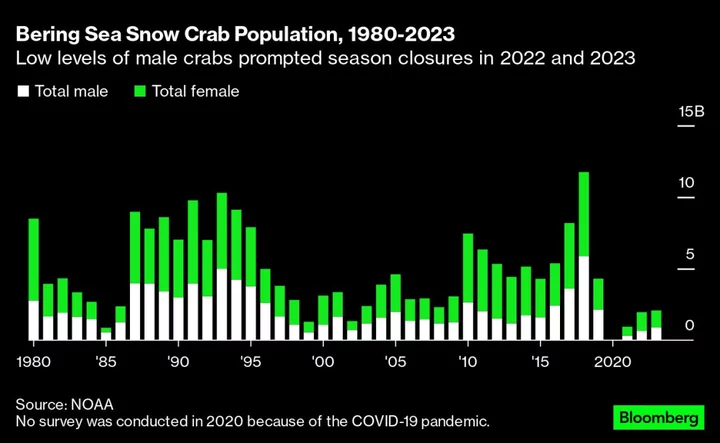

The continent set a target for boosting power generation from renewable energy to at least 300 gigawatts by 2030, from 56 gigawatts in 2022, and made plans to reform carbon markets in order to generate more revenue.

The document rowed back on language in an earlier draft seen by Bloomberg that placed more emphasis on the continent’s potential contribution to fighting global warming by developing carbon friendly industries, such as green hydrogen.

While Africa has abundant solar, wind and hydropower potential and is being touted as a future source of green hydrogen, almost half of Africa’s population, or 600 million people, lack access to electricity. Only 2% of global investment in renewable energy goes to Africa, the leaders said.

There was little mention in the document of reining in Africa’s own fossil fuel industries, which many leaders argue are essential for economic development. Nigeria and Angola are major oil producers and Senegal and Mozambique are on course to produce significant amounts of natural gas. South Africa relies on coal for more than 80% of its power.

(Updates with comments from Kenyan president in sixth, seventh paragraphs)