From the tiny office he shares with five staff, Dutch lawmaker Pieter Omtzigt is planning to transform the Netherlands’s economic relationship with Europe.

The EU risks turning into a “union of debt,” the 49-year-old warned in an interview with Bloomberg. He advocates a bloc-wide return to the stricter, pre-corona rules on members’ debt and deficit ratios, and would like his country to have an opt-out from joint European Union programs.

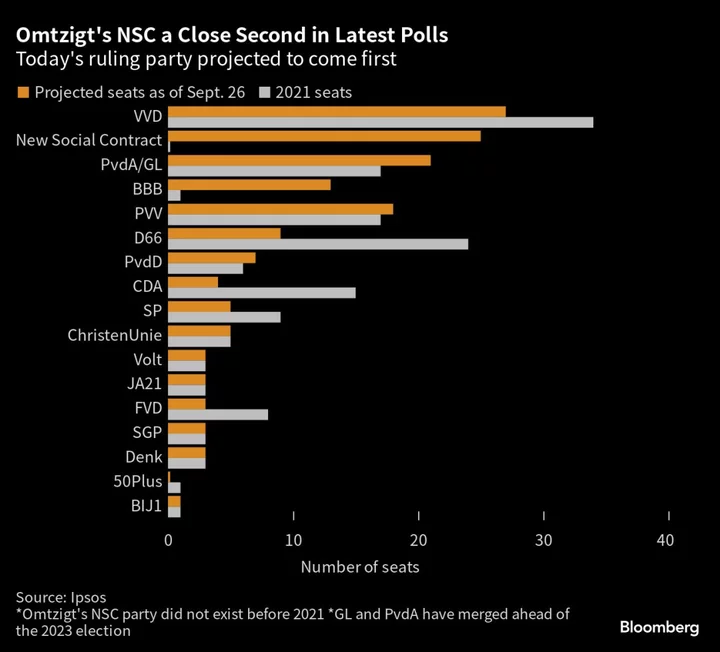

If voting intentions for next month’s Dutch elections hold, fellow parties, EU members and investors will need to take him seriously. Though Omtzigt’s New Social Contract Party is barely two months old, it has spent much of that time placed first in the polls.

A parliamentarian for two decades, Omtzigt won renown in recent years as a thorn in the side of Mark Rutte, who’s resigning after the elections though remains in office as caretaker prime minister. Omtzigt was instrumental in uncovering the child-benefits scandal that collapsed Rutte’s third government at the end of 2020.

When a few months later the prime minister narrowly survived a vote of no confidence, it had been triggered by accusations that he secretly tried to sideline the outspoken lawmaker.

In the interview, Omtzigt took aim at the way Rutte’s cabinet had eased its approach to shared European spending, which he vowed to rein in.

“I am concerned about the accumulation of debt in various places,” he said. “Building up debt is easy, but reducing debt is not.”

“The corona fund is one of a number of things I would have preferred not to happen,” Omtzigt said from his office — its cramped confines reflecting how, after breaking away from the Christian-democrat CDA, he runs a one-man show.

Polls suggest he will soon occupy a more generous piece of real estate. The most recent Ipsos survey had his NSC slipping to close second in a 17-horse race, projecting 25 seats after the Nov. 22 vote, in a fractured parliament whose biggest party today has 26. By contrast, the party that once counted him a member is shown losing 11 of its seats to take four.

When Omtzigt formed his new party in August, its announcement came with the caveat that he had no interest in standing to be prime minister. In the Dutch system, the process of negotiating a government can take months and the head of the first-placed party doesn’t necessarily nab the top job.

Pressed again by Bloomberg, he chose his words more carefully: “We currently have no prime ministerial candidate,” he said of his party. “We’ll take things step by step.”

Having held roles in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, Omtzigt said he’s in favor of European cooperation but doesn’t support an ever-closer union. “The union is always taking on new tasks,” he said.

The ones he assumes himself tend to involve enforcing the rule of law. As special rapporteur on the killing of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, he helped expose a web of back-room dealing that resulted in the resignation of the Maltese prime minister, and is in charge of monitoring judicial freedoms and human rights in Poland.

Omtzigt named minimum-wage decisions as an area that should be left to individual member states, and criticized European Central Bank bond purchases as akin to the sort of monetary financing that is banned in the EU’s foundational treaties.

Though Omtzigt rejects the label euroskeptic, he has been skeptical of the euro. From opposition in 2017 he spearheaded a bill asking the government’s top advisory board to examine how well it was working, despite widespread support for the single currency in the Netherlands.

“I find it interesting that we are still not mature enough in Europe or in the Netherlands so when you criticize a plan from Brussels you are immediately a euroskeptic” he said. “Why should we immediately say yes to any plan from the European Commission? I don’t understand that.”

Of a putative opt-out to European programs, he emphasized that he didn’t think one country ought to have power to veto the decisions of others: “But if you want to do it together, you can do it without us.”

--With assistance from April Roach.