For about two decades, a meat plant in the northwest German town of Vörden has helped produce a bear-shaped cold cut known as Bärchenwurst, beloved by children across the country. But rising production costs and waning demand for pork — even in a nation that once had some of the highest per capita consumption rates — forced the factory’s operator to declare a few weeks ago that it would shut down.

The announcement reflects the embattled state of Germany’s pork industry, which is struggling with a huge drop-off in demand, the aftermath of African Swine Fever, and a raft of economic challenges and domestic animal welfare provisions that have made it especially difficult to raise pigs.

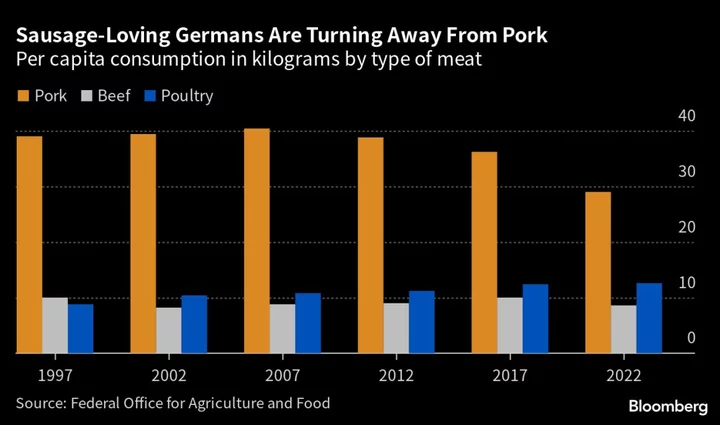

As consumers go, so does industry. While the average German ate some 40 kilograms of pork per year in 2007, that dropped to 29 kilograms in 2022 — even as beef and chicken consumption remained more or less steady. The country’s pig population shrunk by nearly a fifth in the two years leading up to last November, as did the number of pig farms. The Family Butchers, which owns the Vörden plant and is Germany’s second-largest sausage maker, is only the latest to end up under the knife.

Alongside disappearing demand, Eckhart Neun, a butcher from the town of Gedern, about an hour northeast of Frankfurt, explained that soaring energy, fertilizer and feed prices are also putting pressure on smaller businesses like his. “It’s like dominoes, one thing leads to another,” said Neun, who is also vice president of the German Butchers Association.

Pork is losing its luster in various parts of the world, but the trend is especially pronounced in Europe. EU pork consumption is expected to drop to the lowest level in more than two decades this year and within two years production will shrink by roughly a tenth. Producers in the US are also grappling with shrinking profits, waning demand, rising costs and more regulation. Even in China, which accounts for more than half of the world’s pork consumption, the meat is falling out of favor with a rising middle class that views beef as a healthier option, according to McKinsey research.

Still, the situation in Germany stands out, as pork producers are weathering a perfect storm of tough economic trends, broader demographic and cultural shifts, and the aftermath of public health crises that decimated both production and demand.

According to Frank Greshake of the North Rhine-Westphalia Chamber of Agriculture, the federal state with the highest number of pig farms, Germans are generally choosing less meat-intensive diets. The number of people in Germany identifying as vegetarian has grown since 2020, and according to a 2022 nutrition report by the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 44% say they follow a “flexitarian” diet that limits meat consumption.

Health concerns are one reason for the shift: the World Health Organization has warned that eating processed meats like sausages and ham can be carcinogenic. Environmental concerns are another. The ecological costs of raising and eating meat have been a particular focus of Germany’s Green Party, which joined the ruling coalition in 2021.

In addition, Muslims, many of whom do not eat pork for religious reasons, are now estimated to make up nearly 7% of Germany’s population.

But it’s not only people who shun pork out of principle that are weighing on demand — food preferences appear to be changing along generational lines. Younger Germans favor pizza, doner kebabs and burgers over sausages, according to a YouGov survey conducted for news agency DPA last December. And while pork-heavy traditional German food is still the top-ranked cuisine for people above the age of 35, younger adults and women across age groups would rather opt for Italian.

In 2020, the outbreak of African Swine Fever prompted China to block pork imports from Germany, sending producers into a tailspin. Prior to the ban, which is still in place, China was the most important export destination for German pig farmers, who supplied overseas consumers with cuts such as feet, tails and ears. The Covid-19 pandemic also dealt a blow.

But it was last year’s soaring energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that hit German pig farmers especially hard. Piglets, unlike cows, need to have their stalls heated in the winter, which is one reason why pork producers were disproportionately hit by the crisis.

Government efforts to tighten rules around animal welfare is another aggravating factor. For farmers, such regulation can require costly investment in features like outdoor access for animals and more spacious stalls. With fewer people seeking out schnitzel, however, it’s difficult for meat producers to pass these higher costs along to consumers. Moreover, with many farmers nearing retirement age and struggling to find successors, plenty don’t see the point.

“If you’re 55 years old — probably the age of your average pig farmer — you’re no longer going to build” new infrastructure, said Greshake of the North Rhine-Westphalia Chamber of Agriculture. “And in recent years we’ve had massive amounts of new obligations,” he added.

Even farmers who are willing and able to invest in better conditions for animals are still facing difficulties covering their costs, according to Sven Häuser, division manager of livestock farming and on-farm operations at the German Agricultural Society. “We see again and again that the public is just incredibly price-sensitive,” he said. “They say that they are willing to pay more if the animal is better off, but when we talk about inflation of more 10% for food and really every euro has to be counted, then people understandably pay more attention to sales and grab cheaper meat.”

Wolfgang Kühnl, the co-owner of The Family Butchers, lamented the effects that all this could have on the industry. “In ten years,” he said in an interview with Handelsblatt, “the sausage market will probably have shrunk by a third. Of the more than 100 manufacturers, many will give up or be swallowed.”

This has kicked off a conversation among Germany’s pork producers about future-proofing the industry. While scientists tinker with options such as lab-grown meat, old-school sausage-makers are already embracing alternatives. Production of plant-based meats surged 73% between 2019 and 2022, according to Germany’s statistics office. Rügenwalder Mühle Carl Müller GmbH & Co. KG, a large German sausage maker with a nearly two-century-old history, launched its first plant-based products in 2014, and by 2021 it earned more from those than from conventional meat products.

Claudia Hausschild, head of Rügenwalder’s corporate communications and sustainability management, said that this move has better positioned the company to weather the shift away from meat.

“We don’t want to proselytize to anyone or tell them what to eat,” she said. “At the same time, however, we also see that how long we will offer our meat products lies to a certain extent with the consumers.”

--With assistance from Hallie Gu.