Susan Eckert teaches advanced placement biology at Montclair High School in Montclair, New Jersey. Her room sits on the second floor, right next to the lower level's heat-absorbing black tar roof. On hot days, Eckert cracks the windows in her classroom early, then closes them and the blinds as the sun starts to bear down. By the afternoon, though, nothing stops the heat. Eckert has bought five fans for her classroom, which she said registered 90F (32C) on the thermostat this week.

“I watched the weather for a week before school started, when I saw this heat wave coming,” she said. “I was just filled with dread, because it's such a hard way to start school.”

That is, to the extent school can start. On Sept. 5, just 15 hours before the academic year was set to kick off, Montclair’s superintendent announced an abbreviated first day due to “excessively high temperatures.” The decision, based on National Weather Service data, was made in consultation with the district nurse and doctor, the town health office and staff at each of Montclair's 11 schools. It would later be expanded to half-days for the first three days of the school year, each of them reaching the mid-90s.

Montclair is famous for being the childhood home of moonwalker Buzz Aldrin, being the adulthood home of the late Yankees legend Yogi Berra and being worthy of ridicule for its improbable population of journalists, including me.

[Pause for ridicule.]

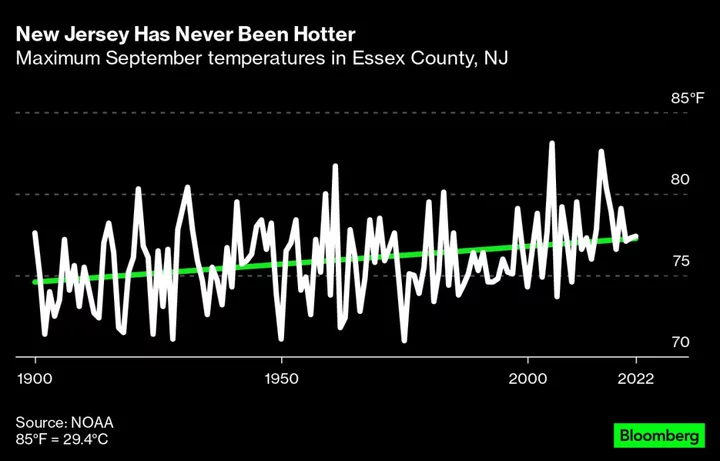

But Montclair is also an unassuming harbinger of the challenges ahead for educators in the era of climate change. The town’s schools are 96 years old, on average; all but one need new air conditioning systems. The average local temperature, meanwhile, has risen 4F since Montclair’s first five schools were built. The daily maximum temperature average for September is up 2.7F.

Research nonprofit Climate Central, whose Climate Shift Index provides a real-time estimate of the effect of fossil-fuel and other emissions on the day’s temperature, can even pin down the degree to which climate change is cooking Essex County, where Montclair is located (Climate Central’s reading is taken in nearby Newark). On four days between Aug. 30 and Sept. 7, the heat was made at least three times more likely by climate change. On Sept. 6 and Sept. 7, the index showed that climate change made the heat four times more likely, making it an outlier even among areas facing heat waves.

Montclair’s situation is far from unique. Dozens of Philadelphia schools abbreviated their schedules this week when forecasts called for temperatures of 85F and higher, in accordance with the district’s Extreme Heat Emergency Response Procedures. Districts in New England, the mid-Atlantic, the Midwest and Texas shortened schedules or canceled school.

And that’s in the world’s richest country, where many towns can vote to install air conditioning in classrooms. India, Mexico and the Philippines, where AC penetration is much lower than in the US, have also canceled classes this year. Iran shut down public life entirely for two days in August, as the air was forecast to reach 122F.

Solving climate change is hard. Preventing heat-related health problems, or deaths, is less so: Air conditioning saves lives. The most recent State of Our Schools update, a report released every five years by three organizations, found the US is under-investing in school infrastructure by $85 billion a year, nearly double the 2016 figure. More than 40% of schools need new or updated heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

In August, Downers Grove, a village near Chicago, delayed the start of its school year by two days because 11 of its 13 schools lack AC. Superintendent Kevin Russell described it as the first time the district had delayed the start of school or canceled school due to heat. For now, the district’s schools rely on a Heat Relief plan that includes rotating classes through limited air-conditioned spaces, keeping fans on, providing water, adjusting outdoor activities and dimming unused lights. A better fix is coming, though: Last year, voters approved a $179 million referendum to modernize the district’s HVAC systems and fund other improvements.

As temperatures continue to rise with fossil-fuel emissions, the urgency is becoming more acute. The Center for Climate Integrity estimates that 13,700 public schools in the US that didn’t need cooling in 1970 will either have or need it by 2025. Ten states, including Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey and Ohio, each face more than $1 billion in costs to cool schools. The analysis found that schools typically install cooling systems when the number of days hotter than 80F reaches 32 a year. Since 1970, the number of schools estimated to pass that threshold has risen by 40%.

There are signs of progress. A state bill in California would order up a master plan for climate-safe schools. In Arlington, Massachusetts, one high school earned poor marks from a New England oversight organization — then the district embarked on a plan to rebuild it.

School districts are also a major issuer in the municipal bond market, tapping investors to raise funds for new construction and renovations. So far this year, public school districts have sold about $44.8 billion worth of debt for both new projects and refinancings, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That's roughly 13% more than was sold over the same period last year, bucking a broader decline in municipal bond issuance, the data show.

Almost half of that debt has come from Texas-based districts where a booming population has underscored the need for more schools.

Last year, Montclair voted to take on a $188 million bond for schools, 40% of which will go to HVAC upgrades that are expected to come online in the next few years. “Climate adaptation will need to be a primary concern” as the design and construction program moves ahead, said David Cantor, the district’s executive director for communications and community engagement.

In the meantime, there are fans. An official from the Montclair High School parent-teacher association this week loaded up a car with a dozen box fans for delivery to classrooms in the most dire need, as students spent their first hours of a new school year trying to learn and think in high heat. “Everyone's fanning themselves,” Eckert said. “It's just very hard to keep their attention, understandably. And the energy in the room is just flat.”

--With assistance from Danielle Moran.