Global leaders are racing to salvage an international deal to allow Ukraine’s grain shipments by sea before it expires in less than two weeks.

They face a key problem: the pact, already extended three times, is nearly defunct.

The nation’s Black Sea ports, bustling with ships last autumn, are almost empty as the joint center tasked with approving them buckles in dysfunction. The few vessels left are being inspected at a trickle. Russian officials continue to rail against the pact’s extension, while Kyiv accuses Moscow of trying to sabotage it.

“It feels different this time,” said Tariel Khajishvili, director at shipping agent Novik LLC in Odesa. Vessel traffic at the key grain hub of Chornomorsk is “completely dead.”

The United Nations and Turkey brokered the grain initiative a year ago to allow a safe route for exports following Russia’s invasion. Since then, the agreement has shepherded almost 33 million tons of crops to global markets, helping to lower food prices and bolstering a sector vital to one of the world’s top grain producers.

It’s up for renewal again July 17, with the European Union, US and UN pushing for an extension. The negotiations take place against the backdrop of Ukraine’s counteroffensive, aided by Western governments, against Russian opposition. The presidents of Ukraine and Turkey are set to meet in Istanbul on Friday to discuss prolonging the pact.

Russia’s foreign ministry this week said there are “no grounds” to continue the pact, citing five obstacles to its own food exports it wants removed. Advocates contend that allowing it to lapse could raise costs for Ukrainian farmers and stifle what the UN calls a “lifeline for global food security.”

“We’re going to see some parts of Ukraine decreasing production for 2024 if nothing changes,” said Kateryna Rybachenko, vice chair of the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club. The country’s grain output is already shrinking under the weight of war, and its exports are set to fall to a decade low. The tumult has prevented farmers from making forward sales of this year’s harvest, she added.

Fading Progress

The export deal whittled down the massive stockpiles that Ukraine amassed after Russia’s invasion halted virtually all seaborne trade. Coupled with crops sold via the EU, Ukraine’s grain exports in the 2022-23 season held even with the one before, ferried across Asia, Africa and Europe.

That progress is fading as the next harvest gets underway: Fewer than two ships a day were cleared in early June, well below export capacity. Moscow has blocked one of the three open ports, and no new ships have been approved since June 26, even as the Ukraine port authority shows nearly 30 registered by the other three sides.

“The deal appears obsolete,” Rabobank analysts including Carlos Mera and Michael Magdovitz said in a report. “Once new crop supplies arrive, seaport access will be critical for Ukrainian agriculture and the global balance sheet.”

In an effort to save the agreement, EU and UN officials are considering giving concessions to a sanctioned Russian bank. Even then, the Russian ministry rejected the compromise, saying it’s unworkable.

Read more: Russia Is Tightening its Grip on the World’s Wheat Supply

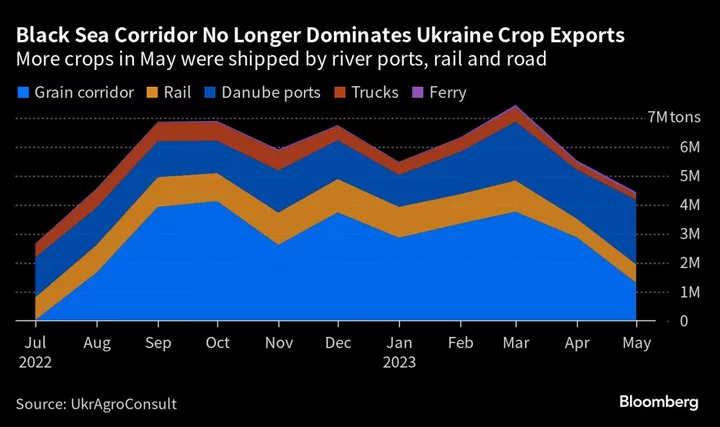

A shutdown would push more crops toward Ukraine’s Danube river ports, plus rail and road transit via the EU border. Those routes have been an economic lifeline: The tonnage now surpasses the volumes moved through the Black Sea corridor, and the government aims for further increases.

It’s also come at a price. Poland banned grain imports from Ukraine due to the effect of a glut on its local farmers. Other governments in eastern Europe have also imposed restrictions.

For Ukrainian exporters, the biggest challenge is cost, which increases as grain is hauled over longer distances and on different-sized rail tracks. “With the cost of logistics which we have now, with the market price we have now, all kinds of grains bring losses,” said Olena Vorona, chief operations officer at agribusiness Agrotrade Group.

Some see a brighter side if the corridor falls through: Black Sea shipments could accelerate should Ukraine opt to keep ports open, unencumbered by the vessel inspections mandated by the deal, said Andrey Novoselov, analyst at Barva Invest.

Kernel Holding SA, the country’s top sunflower-oil exporter, said it’s ready to keep cargoes flowing if the military and infrastructure ministry approve. Ukraine’s government last month created a $547 million insurance fund to compensate companies with vessels going to its Black Sea ports if the export agreement collapses.

It’s not clear whether shipping companies would want to traverse a war zone without the backing of an international agreement. Two Turkish officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, said future Ukrainian shipments look unlikely if the pact ends.

“The problem is which shipowners would be willing to take the risk,” said Khajishvili at Novik in Odesa.

--With assistance from Selcan Hacaoglu, Volodymyr Verbyany, Daryna Krasnolutska and Kateryna Choursina.

Author: Megan Durisin and Áine Quinn