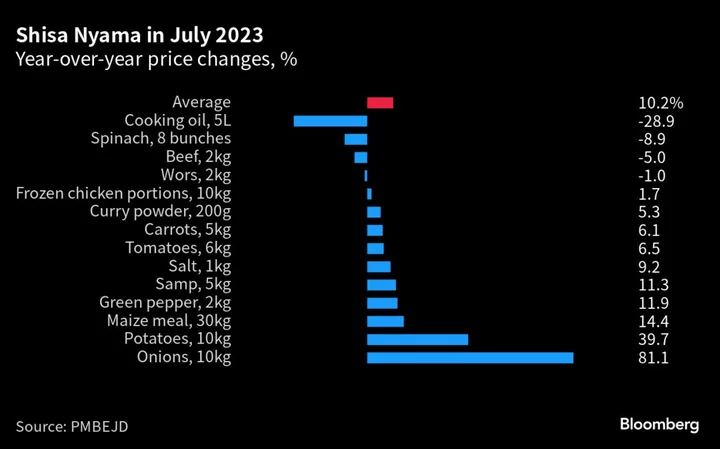

Food prices increased at the slowest pace in at least nine months as the cost of cooking oil plunged, Bloomberg’s Shisa Nyama Index shows, vindicating the central bank’s decision to leave its benchmark rate unchanged after overall inflation slowed.

The cost of a basket of goods in the index, which has been compiled since November and is designed to show the price of a traditional South African backyard barbecue in townships and rural areas, rose 10% in July from a year earlier.

Food prices have remained sticky in many parts of the world because of macroeconomic factors such as weak exchange rates, extreme weather and high energy prices. South Africans have also had to contend with the impact of daily power outages that have raised output costs for food producers.

South African annual food inflation cooled to 11.1% in June from 12% a month earlier, while overall price growth eased to 5.4% from 6.3%, data from the government statistics agency show. That led the central bank to pause its longest phase of monetary-policy tightening since 2006 on July 20, when it left its benchmark borrowing rate at 8.25%.

Read More: South Africa MPC Holds Rates, Warns Inflation Still a Threat

Crunching data from the Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice and Dignity group, Bloomberg’s index tracks the prices of some of the key ingredients in a shisa nyama — potatoes, cooking oil, corn meal, onions, carrots, tomatoes, frozen chicken portions, beef and wors — a type of sausage made from a variety of ground meat offcuts.

More expensive onions and potatoes were the biggest contributors to the year-on-year increase in the Shisa Nyama Index, with the cost of 10 kilograms (22 pounds) of the vegetables soaring 81% and 40% respectively. The price of cooking oil slumped 29%, while the cost of beef declined by 5% and spinach by 9%.

Beauty Dube, a food vendor in Diepsloot, a township north of Johannesburg sells a four-pack of onions and potatoes for 10 rand (54 US cents) each.

“Prices haven’t increased since I started working here in 2021,” Dube said in an interview. “When the supplier increases prices, we reduce the number of items in a pack and I have had to decrease for potatoes and onions mostly” to retain clients, she said.

To compile its survey, the PMBEJD’s data collectors track the prices of 44 food items on the shelves of 47 supermarkets and 32 butcheries that target the low-income market in the greater areas of Johannesburg, Durban, Cape Town, Pietermaritzburg, Springbok in the far northwest and the far northeastern town of Mtubatuba.

This story was produced with the assistance of Bloomberg Automation.

--With assistance from Mike Cohen and Arijit Ghosh.

(Updates with change in meat, vegetable prices in sixth paragraph.)