The debt-limit deal would rein in spending on some federal government services but barely dents the roughly $20 trillion in combined budget deficits projected over the next decade.

The agreement between President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy reached Saturday won’t dramatically shift the nation’s finances because it mostly takes a slice — out of a slice — of the budget known as discretionary spending.

It could be days before the Congressional Budget Office sifts through the ledgers to offer a politically neutral tally of the impact, and then months before the deal’s outline leads to final decisions on funding for individual agencies and programs. But the deal, on which the House intends to vote Wednesday, provides a glimpse of what is to come.

Here’s what is taking shape so far:

Budget Caps

The agreement caps non-defense discretionary spending at just below current levels. Those accounts are a relatively small part of the total budget but include funding for the environment, scientific research, the Department of Justice and more. At a time of 5% annual inflation that means there’s not enough money next year to sustain the same federal government services outside national security areas.

Even in defense, there would likely have to be some selective trims, since the 3.3% increase that the White House and Republican negotiators settled on, and which Biden put in his annual budget request, is also less than the inflation rate.

Both defense and non-defense would then get a 1% increase in 2025, again well below inflation. Republicans had pushed for a decade of tight 1% increases, but the White House refused.

Entitlement Programs

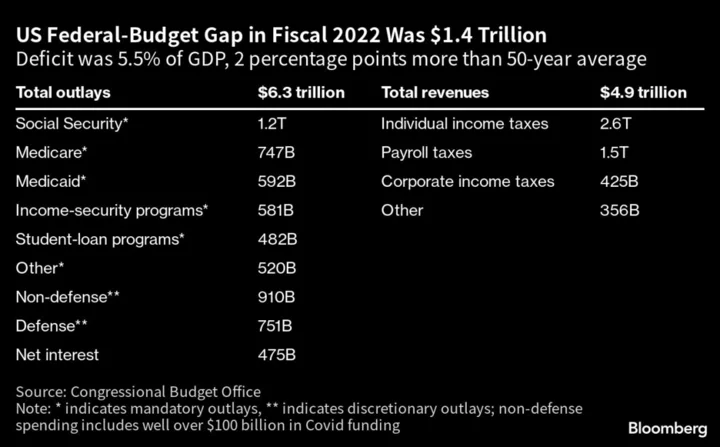

The deal doesn’t touch most of the fast-growing entitlement programs like Medicare, Social Security or Medicaid, which represent the bulk of the budget — as seen in the chart below showing the breakdown for fiscal year 2022.

The deal would also impose new restrictions for the Agriculture Department’s food stamp program — or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program — for 50- to 54-year-olds with no job or dependents. But the Biden administration won agreement for exceptions making it easier to qualify for veterans, homeless people and young adults just emerging from foster care. That is likely to add about the same number of people as leave the food assistance program, a White House official said.

Student loan borrowers, meanwhile, will have to start paying their loans again 60 days after the bill is signed, ending the pandemic-era pause. But the bill does not rescind Biden’s broader student loan relief now being challenged in the Supreme Court.

IRS, Covid

Biden’s team agreed to trim $21 billion over a decade from IRS enforcement and $28 billion from prior COVID spending, which the White House says will help hold domestic agencies to a virtual spending freeze next year. That represents a compromise as House Republicans sought to cancel all unobligated Covid relief spending and most of the $80 billion allocated to the IRS in Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act.

The deal struck would avert a default that was seen as potentially catastrophic for the US economy, but it will only modestly trim overall spending and borrowing. CBO had projected before the deal $6.4 trillion in spending and a $1.57 trillion deficit next year, and it appears the US is still on track to easily spend more than $6 trillion next year.

The final tally of winners and losers won’t be known until Congress completes the annual appropriations process later this year. And the deal includes a new plan to cut spending across the board by 1% if Congress fails to enact regular appropriations bills, meaning that nearly every agency would be affected, especially as costs continue to rise because of inflation.

But Marc Goldwein at Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget says the deal could reduce inflationary pressures by dampening economic growth.

“Let’s say it reduces deficits by $75 billion the first year - that’s about 0.3% of the economy which could reduce inflationary pressure by a quarter point,” he said.

--With assistance from Erik Wasson and Ana Monteiro.

Author: Steven T. Dennis and Laura Davison