When officials from 11 countries across Asia-Pacific and the Americas sat down in Detroit on Friday to discuss deepening and expanding their trade bloc, one country was conspicuously absent: the United States.

That deal — the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership — was once championed by Washington then abandoned as the political winds shifted. Instead, President Joe Biden has been pushing a new plan for trade engagement with the region.

Read more: Understanding IPEF and How It Counters China’s Clout

Biden’s new plan has a different name, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. It’s a piece of the larger puzzle of partnerships Washington assembled to counter Beijing, including security pacts such as the Quad, with Japan, Australia and India, and several bilateral trade and defense agreements, including with South Korea.

Members of the overlapping blocs are meeting this week on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, which the US is hosting for the first time since 2011, culminating with a leaders meeting in November.

The US absence from the meeting about the old trade deal Friday on US soil is a reminder of the missed opportunity, said Bill Reinsch, a former Commerce Department official in the Clinton administration and now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“It does send a signal,” Reinsch said. “It’s a reminder to the US that this important other thing is happening, and we’re not at the table.”

The old deal was promoted and negotiated under the administrations of both George W. Bush and Barack Obama as a way for the US to set the terms of trade in the Asia-Pacific region and push back on what it saw as an increasingly assertive China.

That ambition came to an end in the first days of the Trump administration, which took a more protectionist view. And Biden’s decision not to return highlights the political reality that free-trade pacts have drawn bipartisan opposition — aside from the US Mexico Canada Agreement that replaced an existing pact.

Meanwhile, an even bigger trade bloc has formed under China’s leadership, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. RCEP, as it’s known, advances Beijing-designed standards and other non-tariff policies, further shifting the center of gravity away from the US.

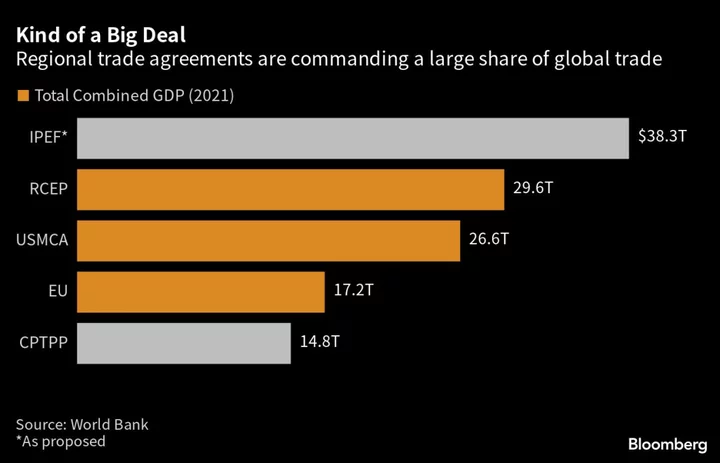

While Biden’s new trade initiative is bigger by one key metric — its countries combined economies total about $38 trillion, compared with nearly $15 trillion for the old deal — one of the key differences is tariffs. IPEF, as it’s known, is avoiding the thorny topic of lower tariffs, instead focusing on other issues such as labor laws, environmental protection and anti-corruption practices.

Critics of the current US approach say it’s hard to commit to the new US initiative if it isn’t offering greater access to its market of 330 million consumers.

Meanwhile, several members of the old bloc are open about their desire for the US to return.

“It’s openly known that we’d all welcome the US at any time that is chooses to come back in,” New Zealand Trade Minister Damien O’Connor said Thursday.

Peru Trade Minister Juan Carlos Mathews said that the existing agreement offers “an extremely broad spectrum of opportunities for any economy, including an economy as powerful as the US.”

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has repeatedly urged the US to come back to the existing deal, including on a trip to Washington in January. So has the US Chamber of Commerce, the largest American business lobby.

The UK is set to become its 12th member after its inclusion was approved in March. Five other governments have applied to join, including Taiwan and China.

Part of the White House’s rejection of the existing Pacific deal is the administration’s “worker centered” trade policy that looks critically at past agreements. While they opened markets for US exports, they also exposed the America to imports from around the world that Democratic allies in the US organized labor movement blame for the loss of hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs.

And support from the Republican Party, which historically backed such deals, practically evaporated amid the popularity of Trump’s trade wars.

The US-led group will hold talks on Saturday and is expected to announce an agreement on supply chain coordination, Bloomberg News reported last week.

Officials involved in the existing Pacific deal said that the plans for their meeting are based on having so many ministers already gathered in the same place, and that similar meetings have happened in other countries when they hosted APEC.

“The schedule has been put together that way,” said Mary Ng, trade minister of Canada. “And absolutely there’s room for both,”