A concrete skeleton looming over Hamburg’s harbor was supposed to be the crown jewel of a historic revitalization project, but on a rainy day this week, cranes and forklifts stood still as uncertainty deepened around the fate of its developer’s finances.

Instead of serving as a modern sentinel for the German port city, the Elbtower has become a monument to the excess of Rene Benko, the embattled mogul who pushed through the office tower even as other developers backed away from risky high-rises.

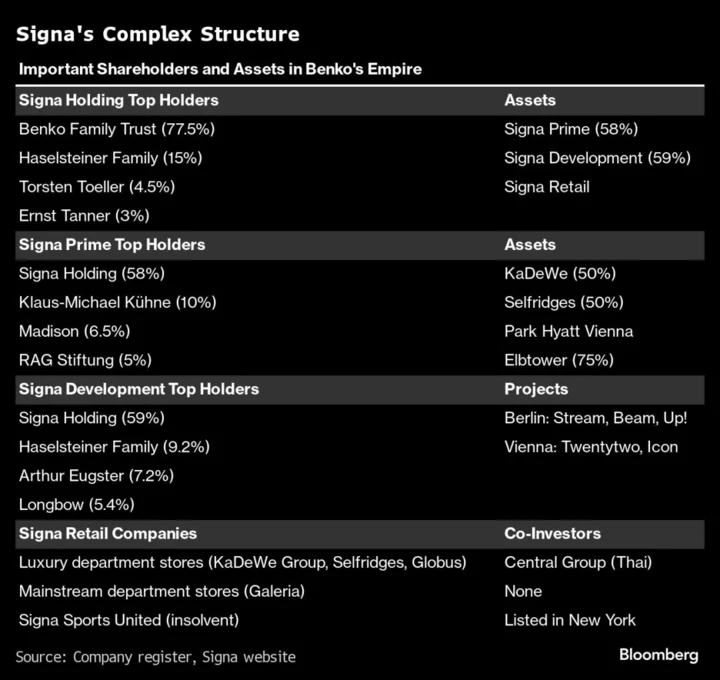

After making his name building a star-studded portfolio that includes partial ownership in New York’s Chrysler building, Selfridges in London and KaDeWe in Berlin, Benko’s €23 billion ($25 billion) empire is now being laid low by a toxic combination of falling valuations, rising financing costs and a lack of liquidity.

Benko announced on Wednesday that he handed over control of his Signa Holding GmbH to a restructuring expert. He pledged to support the turnaround effort and his family trust will remain the largest shareholder, retaining some leverage over other investors.

Located in HafenCity, the Elbtower is the most visible sign of the self-made property tycoon’s implosion. As a book end to the iconic Elbphilharmonie concert hall, it’s supposed to be the keystone of Europe’s biggest inner-city development project, connecting Hamburg’s downtown to the old port. But it’s not the only prime site left in Signa’s hands, nor even the only one in Hamburg.

In the heart of the city, visitors arriving at the main train station were once drawn to the shopping district by two big department stores. Both were part of the Galeria Karstadt Group and were shuttered in 2020 as part of pandemic-induced restructuring. One has been empty ever since, while the other has been turned into an art space by the city.

Rolf Krieger, a gallerist who rents part of the fourth floor in the converted store, is happy he found a new location after Signa terminated his lease last year to redevelop the Gänsemarktpassage — located a few blocks away in the city center.

“It would be a shame if yet another building in such a great location were to stay empty,” he said.

Such scenes may become increasingly common across Germany, as the collapse of Benko’s department store holdings leave gaps in central shopping areas in cities including the struggling steel town of Duisburg, the historic port city of Lübeck and Cottbus, a lignite mining center in the former communist east.

Part of Benko’s strategy was to buy troubled retail chains, portraying the group as a savior. Rather than stores, the main prize was the central locations, which could be redeveloped. During the Covid era, his group took in subsidies to keep the businesses going, but many collapsed soon after the handouts ran out. On top of missing tax revenue, German taxpayers lost €590 million from unpaid Covid-era emergency loans. A similar collapse took place in Austria following Signa’s involvement in the Kika and Leiner furniture chains.

Still, half-finished developments like the Elbtower could present even bigger headaches than empty shops because millions in additional investment are needed before the sites can be usable.

Designed by architect David Chipperfield’s firm to resemble an ocean wave crashing against a barrier and rising into the sky, the Elbtower was supposed to be 245 meters (800 feet) tall, but only reached about 100 meters before construction halted. The project — 25%-owned by asset manager Commerz Real — was slated to open by 2026 and feature a light display that would react to the weather.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz championed the project while he was mayor of Germany’s second-largest city. At the unveiling of the plans in 2018, he called the tower “a self-confident, elegant and beautiful building.” The city’s current administration has threatened to take control of the site if work doesn’t resume soon.

Failing to meet contractual milestones could lead to penalties and trigger repurchase rights for the city, said Karen Pein, Hamburg’s Senator for Urban Development and Housing in a statement on Monday. Her office declined to comment on a time line for any decisions.

Signa’s partners are waiting for work to start again, but have little insight. “Our expectation remains that Signa will fulfill its contractual obligations and that construction activities will resume quickly,” HafenCity said in a statement to Bloomberg.

“There is currently no timetable,” Lupp, the Elbtower’s construction contractor, said by e-mail. “As things stand today, we do not expect construction work to resume in the coming week.”

High-rises are particularly problematic for urban planners. Their huge operating costs and their large footprints make them difficult to convert to other uses. While the Elbtower is also meant to include restaurants, gyms and art galleries, the bulk of the 100,000 square meters of space is intended for offices. But the pandemic and rising interest rates have hit that segment hard.

Read More: Europe’s Aging Banking Towers Hit Hardest by Post-Pandemic Reset

Still, the project might simply be too big to fail for the city. Jan-Oliver Siebrand, head of sustainability and mobility at Hamburg’s chamber of commerce, assumes that construction will be resumed sooner or later: “It’s a temporal, not a structural problem,” he said.

While other Signa projects have also been stalled in Berlin and elsewhere, Hamburg is particularly exposed. A few days before the Elbtower project was stopped, Signa suspended work at the Gänsemarktpassage on Jungfernstieg, one of Hamburg’s main high-end shopping streets.

A former department store at the site was torn down at the beginning of the year to give way for offices and luxury apartments. Signa now says construction will only resume once it finds enough renters.

While Benko, who began his ascent as a teenager by converting attic spaces in the Alpine city of Innsbruck into apartments, had a reputation for getting things done via a mix of strong-arm tactics and Austrian charm, his ongoing struggles may make that more difficult.

The landmark building adjacent to the Gänsemarkt construction site is also owned by Signa, and news that the tenants had to move out by next spring came as a shock to Grüne’s, a pawn shop that had been renting space on the second floor for 20 years.

“In the same letter, the new owners introduced themselves and terminated my lease,” said Berit Schröder-Maas, who manages Grüne’s Hamburg branches. She has since found a new location and is happy to move away from the building site next door and a landlord “who treats tenants with such disregard.”

--With assistance from Marton Eder and Boris Groendahl.