Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey pushed back against market bets on interest rate reductions, saying that officials need to carry on fighting inflation for now.

Bailey reiterated that monetary policy will need to be restrictive for an extended period in comments that appeared to be more cautious about the possibility of lower rates than those made by BOE’s Chief Economist Huw Pill earlier in the week.

“It’s really too early to be talking about cutting rates,” Bailey said Wednesday in response to questions at an event in Ireland. “The market of course will reach a view. It has to reach a view on the future path of interest rates, I understand that. But we’re very clear, we’re not talking about that.”

The governor’s messaging did little to change market expectations. Traders on Tuesday moved to price in more reductions in the BOE’s benchmark lending rate next year after Pill hinted the central bank was open to cutting rates by the middle of 2024, in line with market wagers. Traders are anticipating around 75 basis points of decreases for the first time, up from just 30 basis points last month.

Bailey pointed out difficulties the BOE has in reining in Britain’s inflation rate, which remains the highest in the Group of Seven. He noted that the UK’s potential growth rate has fallen sharply from over 2% during most of his career to “a bit over 1%” since the pandemic, which indicates the limits the economy can grow without pushing up prices.

That remark chimed with a separate report from the National Institute of Social and Economic Research, which on Wednesday warned that the UK faces a “decade in the doldrums” unless the government boosts public investment. The economic think tank predicted anemic growth and deepening regional inequalities, calling on Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to back a revival of investment over pre-election tax giveaways.

Britain’s low growth rate, Bailey said, “complicates the setting of monetary policy.” He blamed those woes on an aging population, weak productivity and a withdrawal of workers from the labor force.

NIESR said public investment needs to rise to 3% of GDP per year to address an economic malaise that means that low to middle income households are undergoing seven years of falling living standards. It predicted lackluster growth of just 0.6% in 2023 and 0.5% in 2024 ahead of the autumn fiscal statement from Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt.

“The lack of public investment is a large part of the UK’s slow growth story,” said Stephen Millard, deputy director for macroeconomic modeling. “That’s what they should be doing. We don’t want to see a pre-election tax giveaway.”

The think tank said that slow growth is partly due to higher interest rates to tackle inflation. Bailey warned they may settle at higher levels.

On the topic of the neutral interest rate — or where rates would need to be to hold inflation steady at the target of 2% — Bailey said the considerations for the long-run and short-run were pointing in opposite directions.

In the long-term, an aging population suggested we are “going back to low rates,” he said. This conflicts with arguments from some other economists, who argue an older population will push up rates. In the short-term, however, a tight labor market and a mismatch between job vacancies and the workers available for the roles pointed the opposite way, Bailey said.

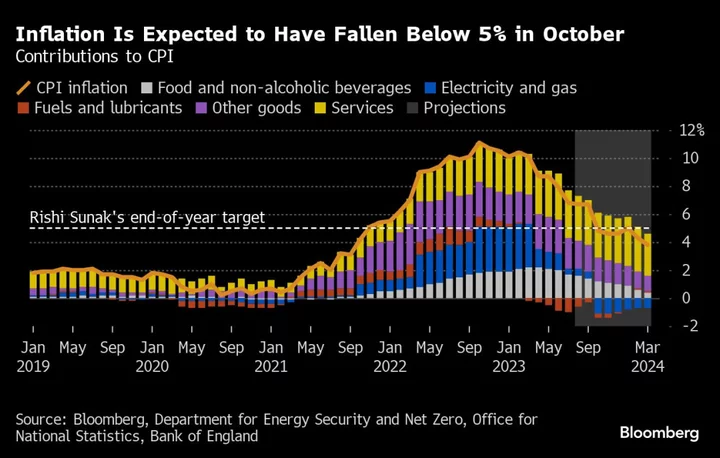

Bailey reiterated remarks he and Pill have made in recent days anticipating a sharp drop in inflation when the latest figures are published next week and that it’s likely to drop back to the 2% target within two years. That thought has prompted investors to bet that the BOE will soon shift its focus away from inflation and toward supporting an economy that some analysts think already may be in a recession.

Bailey dampened those hopes, repeating that policy makers aren’t yet talking about rate cuts because of risks that inflation will persist.

The governor said the first half of the fight against inflation had been about the unwinding of large shocks to the economy, with energy prices slipping from high levels and supply chain frictions easing. But the second half of the battle, he said, will require monetary policy to remain “restrictive” for long enough to wrench expectations for soaring prices out of the minds of consumers.

Repeating wording from the minutes of the BOE’s Monetary Policy Committee meeting this month, Bailey said, “What we’re saying is policy is going to have to be restrictive for an extended period to see the second half out, which is where policy is going to have to do the work to bring inflation back to 2%.”

--With assistance from Andrew Atkinson, Philip Aldrick and Irina Anghel.

(Updates with comment, market reaction and NIESR remarks.)