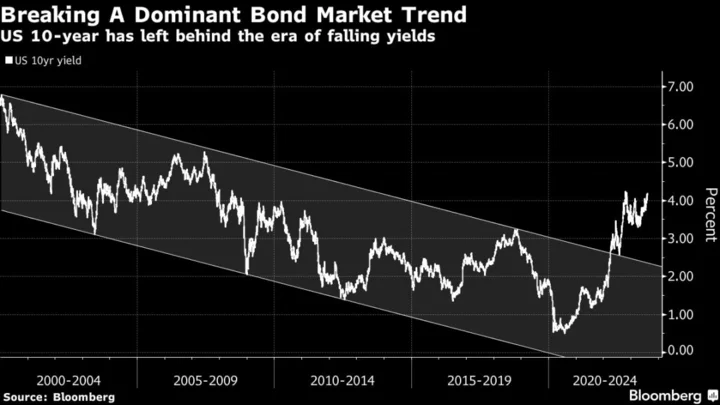

All around the world, bond traders are finally coming to the sobering realization that the rock-bottom yields of recent history might be gone for good.

The surprisingly resilient US economy, ballooning debt and deficits, and escalating concerns that the Federal Reserve will hold interest rates high are driving yields on the longest-dated Treasuries back to the highest levels in over a decade.

That’s prompted a rethink of what “normal” in the Treasury market will look like. At Bank of America Corp., strategists are warning investors to brace for the return of the “5% world” that prevailed before the global financial crisis ushered in a long era of near-zero US rates. And BlackRock Inc. and Pacific Investment Management Co. say inflation could remain stubbornly above the Fed’s target, leaving room for long-term yields to push even higher.

“There is a remarkable repricing higher in longer-term rates,” said Jean Boivin, a former Bank of Canada official who now heads the BlackRock Investment Institute.

“The market is coming more to the view that there is going to be long-term inflation pressures despite recent progress,” he said. “Macro uncertainty is going to remain the story for the next few years, and that requires greater compensation to own long-dated bonds.”

It’s a sharp break for markets that last year started positioning for a recession that would push the Fed to ease monetary policy, raising hopes for a sharp rebound from a brutal 2022 that sent Treasuries to the deepest losses since at least the early 1970s.

While higher rates will soften the blow by boosting bondholders’ interest payments, they also threaten to weigh on everything from consumer spending and home sales to the prices of high-flying tech stocks. What’s more, they will increase the US government’s financing costs, worsening the deficits that are already forcing it to borrow some $1 trillion this quarter to cover the gap.

The selloff since last week has hit those long bonds the hardest and wiped out the broader Treasury market’s gains this year, putting it on pace for the third straight annual loss. It has also pulled down stock prices, which rallied strongly until this month on expectations about the Fed’s path.

It’s possible the latest turn will prove off base, and some Wall Street forecasters are still calling for an economic contraction that would put downward pressure on consumer prices.

Moreover, inflation expectations have remained moored this year as the pace slowed sharply from last year’s highs, a sign the market is anticipating it will eventually draw back near the Fed’s 2% target. The personal consumption expenditures index, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, rose at a 3% pace in June. That’s down from as much as 7% a year earlier.

But many now expect a soft landing that would leave inflation the dominant risk. That was underscored this week by the release of the Federal Open Market Committee’s meeting minutes from July, when officials expressed concern that more rate hikes may still be needed. They also indicated the Fed may keep paring its bond holdings even when they decide to ease rates to make policy less restrictive, threatening to keep another drag on the bond market.

That helped to push Treasury yields up for a sixth straight day Thursday, with those on benchmark 10-year notes climbing as high as 4.33%. That’s just shy of the October peak, which was the highest since 2007. Thirty-year yields hit 4.42%, a 12-year high.

Broader economic shifts are also driving speculation that the low rates — and inflation — of the post-crisis period were an anomaly. Among them: demographics that may push up wages as aging workers retire; a shift away from globalization; and drives to combat global warning by shifting away from fossil fuels.

“If inflation is going to be sticky and high, I don’t want to own long-term bonds,” said Kathryn Kaminski, chief research strategist and portfolio manager at AlphaSimplex Group.

“People are going to need more term premium to own long-term bonds,” she said, referring to the higher payments investors normally demand for the risk of parting with their money for longer.

Even with the recent rise in yields, though, no such premium has returned. In fact, it remains negative as long-term rates hold below short-term ones — an inversion of the yield curve that’s usually seen as a harbinger of a recession. But that gap has started to narrow, cutting a New York Fed measure of the term premium to around minus 0.56% from nearly 1% in mid-July.

That upward pressure has also been exacerbated by US federal spending, which is creating a flood of new debt sales to plug the deficit even as the economy remains at — or near — full employment. At the same time, the Bank of Japan’s decision to finally allow 10-year yields there to push higher will likely cut Japanese demand for US Treasuries.

BlackRock’s Boivin says there’s major shift underway at the world’s central banks. For years, he said, they kept interest rates well below the rate that’s considered neutral to spur their economies and ward off the risk of deflation.

“This has been flipped now,” he said. “So even if the long-term neutral rate is not changed, central banks will hold policy above that neutral rate to stave off inflationary pressure.”