The United Auto Workers’s historic standoff with Detroit’s three carmaking giants is centered on an age-old tension: The union says corporate greed is keeping workers from earning fair wages, while Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co. and Stellantis NV say they can’t afford union demands.

While both arguments have some merit, one fact stands out: The 10 individuals who’ve served as chief executive officers of the companies since 2010 have collected more than $1 billion of compensation. Meanwhile, wages of US auto workers — unionized or not — have declined around 17% in that time frame.

This reality underpins the strike now entering its fifth week that’s playing out against the backdrop of growing income inequality and rising executive compensation. “We went backward in wages in the last 15 years,” UAW President Shawn Fain told reporters last month. “Hell, most of our members can’t even afford to buy what we make.”

The $1 billion total that Detroit carmaker CEOs have taken home includes salaries, bonuses, the value of stock awards, fringe benefits and special payouts linked to retirement or corporate transactions. A spokesperson for Stellantis noted that recent mergers resulted in large one-time pay packages for the previous CEOs.

The median worker at GM and Ford earned $80,034 and $74,691 in 2022, respectively. Stellantis, which is based in the Netherlands, paid its average employee €64,328 ($67,800) last year. At both GM and Ford, that puts CEO-to-worker pay ratios higher than the average among the biggest publicly traded US firms, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Stellantis said that it has distributed more than €2 billion in profit-sharing to employees under the current CEO Carlos Tavares.

In filings, each of the companies say that most CEO awards are tied to performance targets. If results worsen, payouts shrink. GM CEO Mary Barra said as much in a recent interview, noting that 92% of her pay is based on performance of the company.

Each of the current CEOs, however, gets an annual salary of at least $1.7 million, regardless of performance.

While the amounts make for good picket-line material, they’re not unique. Corporate boards across industries have for decades doled out bigger and bigger packages to CEOs, leading to a growing divergence between how corporations in the US and beyond have rewarded workers relative to their top bosses.

Real Wages Really Are Down

Wages are one of the major sticking points in union negotiations. The UAW initially asked for 40% hikes and wants to emerge from its strikes with at least 30% raises, people familiar with the matter told Bloomberg. So far, Ford says its offer of a 23% raise is as high as it can go, while GM and Stellantis have been reluctant to offer much more than roughly 20% increases.

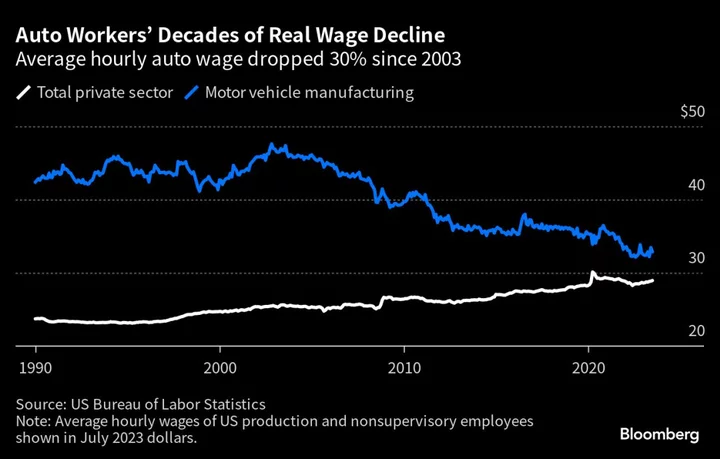

There’s good reason for the ask: Since 2003, the average hourly wage for US auto workers has declined about 30%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Among the factors contributing to this trend was the rise of non-unionized car production in the US and the UAW agreeing in 2007 to lower wages for new hires at Detroit Three plants.

While Fain has described what some of his members make as “poverty wages,” those employed in vehicle manufacturing still make more than the average private-sector worker — albeit by a narrowing gap. UAW members also make more than non-unionized workers in the sector.

GM’s CEO Barra has said the company’s labor costs are already $22 an hour more than electric-vehicle leader Tesla, and that this competitive disadvantage would only grow as a result of the UAW’s asks.

$242 Billion Pension Risk

Fain has made it part of his mission to undo concessions agreed to during the Great Recession. Among the benefits sacrificed were pensions — any worker hired prior to 2008 has one; anyone who’s joined since doesn’t.

Legions of companies across industries have scrapped or frozen pension plans because they’re costly. One study found that companies save 13.5% on long-term employee payroll costs when they freeze defined pension benefits.

Since 2005, GM has cut its retirement obligations by almost 70%, according to Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Steve Man. Ford has trimmed its pension liabilities by almost half in that same time frame.

If GM and Ford were to meet the union’s asks, their pension liabilities would double to $242 billion, Man estimates.

Rather than bring back pensions, the automakers are willing to increase company contributions to 401(k) benefit plans. GM, for example, has offered to boost its unconditional company contribution to 8%, from 6.4%, while Stellantis is offering a 6% contribution, plus a 50% match for employees who contribute up to 6%.

These plans seem to be a bit better than average. Employers offer a wide range of retirement benefits, said Dan Doonan, executive director of the National Institute on Retirement Security, with some offering nothing at all. Generally, though, a 401(k) match in the range of 4% to 5% is pretty typical, he said. Among Fidelity Investment plans, the average employer match is 4.8%.

Fewer Jobs to Go Around

As the industry transitions to EVs — a shift that will be funded in part by billions in government subsidies — the union wants some guarantees for worker job security.

In the last 20 years, GM, Ford and Stellantis and its predecessors have closed or spun off at least 65 plants, according to the union. The fear is that as EV production and demand picks up, more plants making gas cars and trucks — and the engines and transmissions that power them — will shut.

The automakers, for their part, point to factories they’re opening up rather than shutting down. Ford is building its first new US auto-assembly plant since 1969 in Tennessee. Stellantis opened a Jeep factory — the city’s first assembly plant in decades — in Detroit a few years ago.

The companies also are spending billions along with joint-venture partners on battery plants that the UAW wants to organize. So far, just one of those factories — run by GM and South Korea’s LG Energy Solution — is operating, and it currently pays its newly unionized workers about $20 an hour, which is about one-third less than the automakers’ top wage.

Last week, the UAW spared the car companies from strike expansion after GM agreed to bring battery plant workers into the fold of the union.

The UAW’s aim is to leverage that victory into organizing more factories making EVs and batteries, including those run by Tesla. But reversing the declining fortune of the US auto worker will be a tall order.

--With assistance from Gabrielle Coppola, Keith Naughton, Jo Constantz and Chloe Whiteaker.

(Corrects spelling of UAW president’s name in third paragraph.)