China’s lapse into deflation is emerging as the latest risk for its struggling stock market, denting investor optimism over a much-anticipated earnings rebound.

The CSI 300 Index just capped its worst week since March after a drop in consumer and producer prices added to signs of deterioration in the economy. The benchmark of onshore Chinese shares has now erased more than half of the gains spurred by the Politburo’s policy vows in late July. Hopes that earnings will offer fresh catalysts are giving way to fears that companies may lose pricing power.

While few expect China to experience the decades-long deflationary spell that has haunted Japan, Beijing’s reluctance to deploy forceful stimulus in the face of weak consumption and a property market slump can keep prices muted for longer. Without a healthy dose of inflation, which generally helps buoy corporate revenue and profits, the stock market risks being stuck in the doldrums.

“Lack of inflation means lack of pricing power,” said Mohammed Zaidi, investment director at Nikko Asset Management. “Investors should re-calibrate their earnings expectations for slower growth.”

China’s economy has shown increasing strains in recent weeks, with a sharp deterioration in July imports underscoring how domestic demand remains sluggish despite Beijing’s efforts to restore confidence. The nation’s banks extended the smallest amount of monthly loans since 2009, data showed on Friday, adding to signs that recovery in the world’s second-largest economy is faltering.

That suggests a turnaround in earnings may take longer than thought, with early readings of the second-quarter results already having painted a bleak picture.

Some companies have already been forced to reduce prices to survive against the weak macro backdrop. Analysts warn that businesses may fall into a vicious cycle should consumers choose to defer purchases on expectations of more price cuts, prompting companies to sacrifice profits to woo buyers.

Forward earnings estimates for firms on the MSCI China Index are edging lower again in August after rising for the first month this year in July, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

“There is a risk of corporate earnings being revised downward,” said Wilfred Sit, chief investment officer at Hang Seng Investment Management. “What we need to see now is whether the government is able to come up with some kind of effective policies to boost the economy.”

The CSI 300 Index fell more than 3% this week, while a gauge of Chinese shares listed in Hong Kong posted a second week of losses. Both underperformed the broader MSCI Asia Pacific Index.

Foreign investors, who snapped up onshore Chinese stocks for two weeks amid the optimism spurred by the Politburo meeting, sold each day this week, withdrawing a net 25.5 billion yuan ($3.5 billion) in all. That was the most for any week since October.

For some investors like William Fong, though, the deflationary threat is less of a concern.

“Some people may feel a bit worried, but for us, we actually think it will give policymakers more room to boost the economy,” said Fong, head of Hong Kong China equities at Baring Asset Management Asia Ltd. “If they want to cut the interest rates, if they want to cut reserve requirement ratio, they can do it.”

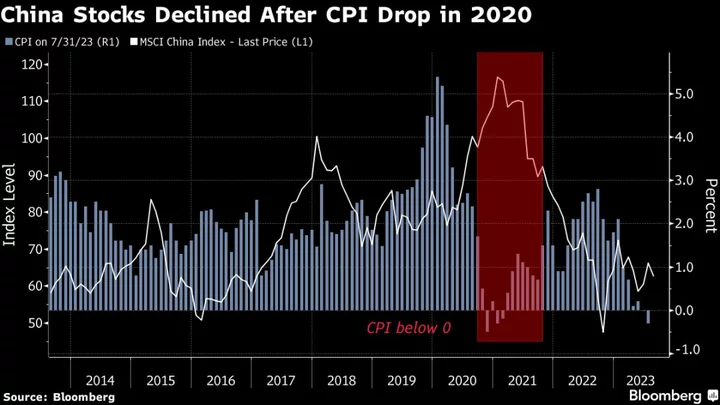

It’s also not the first time that China has experienced deflation. Consumer and producer prices fell in tandem in 2009 and 2020. Stock performances back then have been mixed — the MSCI China Index rebounded during the earlier bout of deflation, but entered a downward spiral shortly after the latter period.

But there are reasons to be more worried now. Incremental incentives to boost spending have so far been insufficient to excite consumers and businesses scarred by years of Covid restrictions.

Authorities also don’t have the fiscal firepower to stimulate the economy. Nor are they willing to aggressively cut interest rates lest it will further increase leverage or add pressure on the already-weak yuan.

READ: China’s Reluctance on Stimulus Will Cap 2023 Growth

Another complication is that China is grappling with deflation at a time when most parts of the world are still tackling stubbornly high inflation. The divergence in monetary policy, which is weighing on the yuan, is a problem for many MSCI China Index members, which do business in the Chinese currency but have shares trading in US dollars.

“The deflation phenomenon needs a more concerted approach” but policymakers are preoccupied with managing the property market crisis and worried about further divergence with US rates, said Aninda Mitra, head of Asia macro and investment strategy at BNY Mellon Investment Management. “But doing nothing is steadily unwinding what little sentiment boost they managed to perk up in late July.”

--With assistance from Ishika Mookerjee.