Ireland’s imminent budget announcement may succeed in turning a fiscal position that impresses everybody into a policy announcement pleasing no-one.

The country is on track to achieve one of the only surpluses in any euro-area country member this year and next, driving competing calls on Finance Minister Michael McGrath and Minister for Public Expenditure Paschal Donohoe to spend big.

That pressure, forcing tough choices between pre-election giveaways and much-needed investment, is intensifying before the 2024 budget is unveiled on Tuesday in Dublin as they confront a slowing economy that narrows their room for maneuver.

The public finances boast a budget surplus over €10 billion ($10.5 billion) thanks mostly to corporate tax receipts from the major multinationals based in Ireland.

The boon is such that the government is setting up a sovereign wealth fund similar to the one Norway has to hoard its oil wealth. But the country is also badly in need of investment in creaking infrastructure suffering from years of underfunding.

With reports of fraught discussions and a flurry of final negotiations, ministers are lobbying for additional funding for respective departments, while many voters are hoping for aid to help ease the burden of persistently high inflation.

“I think we are going to see a budget that is deemed to be a little generous — and probably leave many economists very annoyed — but equally will leave most in various factions who are asking for very significant increases equally disappointed,” said Austin Hughes, an independent economist tracking Ireland.

Ireland stands out from its EU peers, most of whom are still nursing budget deficits as they cope with the lingering fiscal fallout from the pandemic.

In May, the European Commission predicted Ireland and Cyprus would be the bloc’s only members — out of 20 — to enjoy a fiscal surplus in 2023, and also in 2024. While though those numbers will be soon superseded by new budget estimates currently being unveiled across the region.

Ireland’s debt as a percentage of gross domestic product is only 40% — a full 100 percentage points lower than Italy.

The government is keen to use some of its extra cash to win support before an election in the next year or so, just as the opposition Sinn Fein party consistently leads opinion polls.

The central bank has warned the government risks keeping inflation higher for longer, while the budgetary watchdog — the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council — has urged ministers to avoid “past mistakes” and shirk from the temptation of spending increases or tax cuts.

Loretta O’Sullivan, EY Ireland’s chief economist, cautions that there is still a case to offer “one off” aid measures to citizens still confronting the inflation shock.

Speaking at an EU Summit in Spain, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar confirmed that the budget will include supports, particularly around energy.

“Electricity prices have fallen, but they’re still substantially higher than they would have been two winters ago,” he said. “We understand that as a government, and we have the money to help people with those bills, and we will.”

McGrath, the finance minister, previously warned a meeting of his Fianna Fail party that it won’t be possible “to do everything” in the budget.

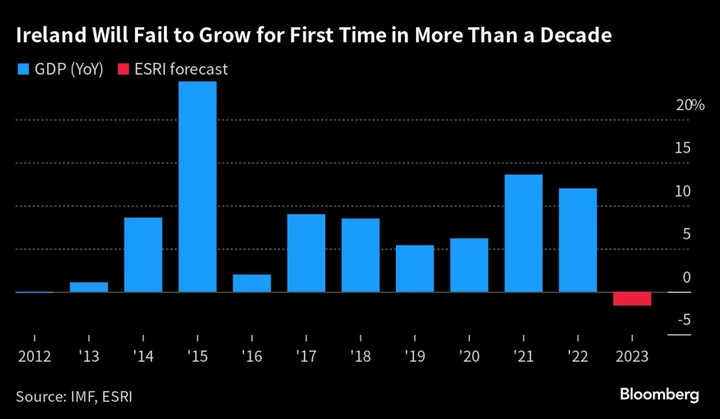

What’s not helping him is a slowing economy. This week, the country’s Economic and Social Research Institute forecast a contraction in the final months of this year, while Exchequer figures showed a drop in corporation tax receipts.

O’Sullivan at EY is sanguine about that.

“We’ve had an exceptional performance,” she said. The economy “is growing, but over the coming years, we expect the growth to be more moderate than we’ve had in the past couple of years.”