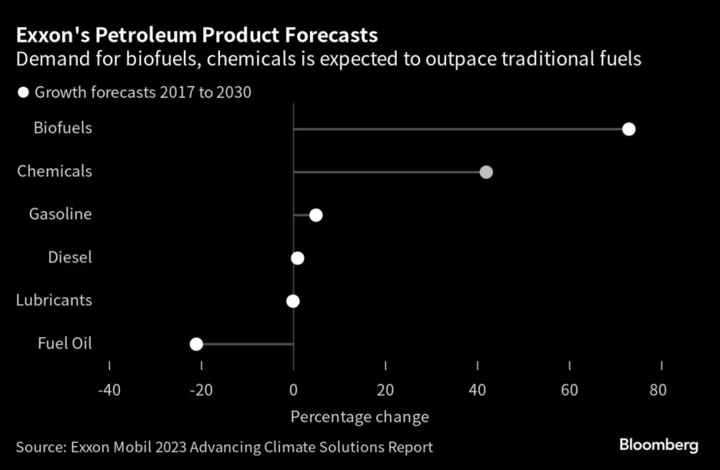

Exxon Mobil Corp., which operates one of the world’s biggest oil-refining networks, is trying to be more responsive to changing consumer demands as the energy transition gathers pace. The changes it’s considering include potentially replacing some gasoline production with chemicals.

The oil giant has long pursued a strategy of upgrading refineries to expand production and make higher-value products from crude oil such as lubricants and plastic feedstock. But it now sees those projects potentially helping the company to move away from traditional fuels, demand for which is likely to wane in coming decades.

The strategy, discussed by this week by executives at a presentation to investors and media, shows how even Exxon, one of the leading proponents of fossil fuels, is being forced to reckon with a future in which electric vehicles significantly eat into gasoline consumption.

Exxon has already reduced production of fuel oil and high-sulfur petroleum at refineries in Singapore and the UK. Over time, it’s open to cutting output of gasoline, the focus of the company’s refining business since Henry Ford introduced the Model T nearly 100 years ago. The goal is to produce more chemicals, found in everything from paint to plastic, for which there are few low-carbon alternatives.

“We’re planning on modifying some of that yield from gasoline to distillate and chemicals feed,” Jack Williams, Exxon senior vice president, said Wednesday at the company’s office in Spring, Texas. “We’ve got projects that we know we would do to take those steps.”

Exxon gets most of its earnings from oil and natural gas production but refining has always been in its corporate DNA, right back to its original incarnation as part of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, which was established in the 19th century.

Refining allows Exxon to earn money right along the fossil fuel supply chain, from the wellhead to the gas tank. But with traditional fuels such as gasoline under threat from EVs, refineries worldwide are being forced to adapt quickly. Some European plants shut down during the pandemic, while others in the US switched to biodiesel.

Read More: Exxon Eyes $10 Billion Earnings Lift in Fuels, Chemicals by 2027

Exxon wants to take a more nuanced approach by upgrading facilities to switch in and out of products depending on demand. To give an example, an Exxon refinery in Singapore used to produce fuel oil that sold for $10 per barrel below the price of Brent crude, but after a recent upgrade, the facility produces lubricant base stocks that sell for $50 above Brent.

Exxon has upgraded and added to its refineries at Fawley in the UK and Beaumont in Texas to produce more diesel, which is used for heavy-duty transportation and is less vulnerable to competition from electric vehicles.

“You just have more variables now due to the energy transition,” said Jay Saunders, a natural resources fund managers at Jennison Associates, which has $186 billion under management. “Having a high-quality refining asset with flexibility will be very important.”

Exxon’s refining and chemicals footprint is at least double that of its Big Oil competitors, potentially making it more vulnerable to a speedy energy transition, and especially the growth of electric vehicles. But executives believe the potential for reconfigurations is far greater than that of its peers, providing an opportunity to profit in a low-carbon future.

“This really allows us to pivot as demand evolves,” said Karen McKee, President of Exxon’s Product Solutions division.

Biodiesel is particularly attractive to Exxon because reconfiguring its existing refineries costs about half as much as building a new plant, said Neil Hansen, senior vice president of product solutions. Demand for biodiesel, which is manufactured from vegetable oil or recycled restaurant grease, is expected to quadruple to 9 million barrels a day by 2050, he said.

Exxon is halfway through an eight-year plan to overhaul its fuels and chemicals division, which also involves cutting costs, improving operational performance and selling assets that don’t make the grade. Exxon will operate just 13 refineries worldwide by the end of 2023 after selling five in the past four years to focus on the biggest and lowest-cost operations.

Chemicals will be key to the strategy’s success. Exxon sees demand growth for its high-performance chemicals at about 7% a year, contrasting sharply with gasoline, which is expected to peak globally by the end of the decade. To keep up with this demand, Exxon plans to build a new dedicated chemical plant every four to seven years, Williams said.

The company’s refineries provide an additional means to make chemicals, but they will focus on responding to consumer preference rather than making a big bet on any particular product, Williams said.

“We’re not going to do it while the demand is still there,” he said. “We’re going to it at a time when the demand trends are clear and customers don’t need that gasoline.”