Soaring corporate profits are a big part of the inflation problem, and keeping interest rates high is the best way to rein them in, according to Bloomberg’s latest poll of professional and retail investors.

Some 90% of 288 respondents in a Markets Live Pulse survey said companies on both sides of the Atlantic have been raising prices in excess of their own costs since the pandemic began in 2020. Almost four out of five said that tight monetary policy is the right way to tackle profit-led inflation.

One of the worst bouts of inflation in decades has spurred a search for explanations – with broken supply chains, big-spending governments and rising wages all shouldering some of the blame. But the surge in corporate markups is another potential cause that deserves attention, and is now getting it.

Read more: Isabella Weber Explains the Big Rethink on What Causes Inflation

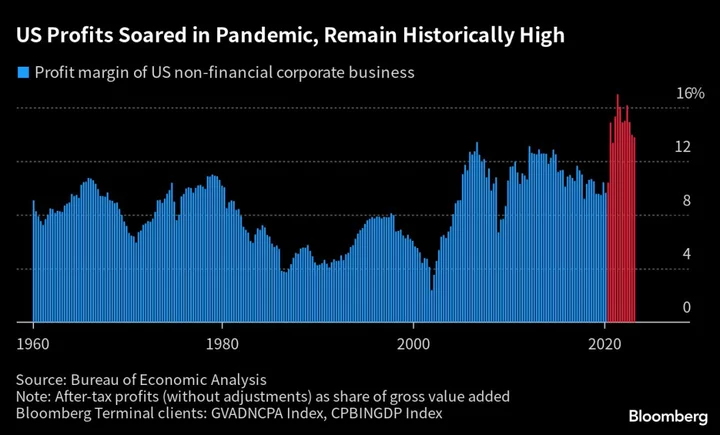

Margins soared in the initial pandemic years, and have defied convention by remaining historically high since then. That raises two key questions: Are fatter profits helping to entrench inflation, and if so, what should be done about it? It’s part of a wider debate about whether different kinds of price pressures need different tools to address them, instead of the one-size-fits-all response of higher interest rates.

MLIV Pulse survey participants largely took the view that monetary tightening by central banks is the appropriate response to profit-driven price rises. About one-quarter disagreed, offering alternative solutions including the use of corporate tax rates against price gougers, and tougher anti-monopoly rules.

The retail sector has seen the most opportunistic pricing during the pandemic, some 67% of respondents said. The energy industry came a distant second, with about one-sixth of votes. Those findings may reflect the fact that people buy basic consumption goods more often than bigger-ticket items, so they’re likelier to notice when the prices jump – an idea known as “collision frequency.’’

The unique circumstances of the pandemic – severe supply constraints, followed by an unprecedented burst of stimulus-fueled demand – lie behind the widening of profit margins, which hit 70-year highs in the US.

That’s unlikely to prove permanent, according to most survey respondents, who expect margins in the aggregate will recede to where they were before Covid – although the majority was only a slim one, at 53%.

Standard economic theory holds that profit margins are “mean-reverting’’ – in other words, they tend to be pulled back to normal levels. It’s supposed to work like this: An industry with high profits should attract new entrants, with increased competition forcing margins lower.

But reality has rudely refused to conform. Margins were already elevated before the pandemic, and they’re now even more so.

Various theories have sought to explain why this happened. Isabella Weber, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, argues that much of the US’s recent inflation is “sellers’ inflation,’’ stemming from the ability of dominant firms to exploit their monopolistic position in order to raise prices. Weber notes that “bottlenecks can create temporary monopoly power which can render it safe to hike prices not only to protect but to increase profits.’’

Paul Donovan, chief global economist at UBS AG, refers to this as “profit-led inflation’’ – companies using the cover of broad-based price increases to raise their own prices more than they have to -- and more colloquially the idea has become known as “greedflation.’’

However it’s labeled, if firms have been taking advantage of monopolies to raise their margins, they will be loath to lower them by much. Who wants to award themselves a pay cut right after getting a raise?

Margins are beginning to fall from their highs as firms rebalance the price-versus-volume trade-off, but they remain significantly higher than in the pre-Covid years.

This could well continue to favor some equities. When asked what type of stock stands to benefit the most from profit-led inflation, almost three-quarters of respondents opted for firms with strong pricing power. The logic there is that until a rising backlash against monopolies or oligopolies gets properly underway, it makes sense to own the companies which can exploit the inflationary backdrop the most.

Ultimately “greedflation’’ is not likely to lead to prolonged sticky inflation, according to a majority of survey respondents.

Only 10% said it will take more than five years for the headline rate of US consumer-price inflation to return to a stable average around 2%. More than half reckon inflation will return to 2% levels within two years – in line with the market view, based on the current two-year breakeven rate of about 2.1%.

So what can be done specifically to stem profit-led inflation? The 24% of survey respondents who don’t believe tighter monetary policy is the answer came up with some thoughtful alternatives.

Among the frequent suggestions were better enforcement of antitrust laws around mergers, along with other efforts to stimulate more competition. There was support for higher corporate taxes, potentially including windfall charges in areas where price-gouging is identified. “Tax them to oblivion’’ was one blunt recommendation.

Inflation breeds resentment by exacerbating inequality. Once pandemic savings are depleted that resentment has the potential to mushroom, and firms’ profit honeymoon will likely face a much more challenging and regulated future. In that case, tighter monetary policy could be the least of their worries.

MLIV Pulse is a weekly survey of Bloomberg News readers on the terminal and online, conducted by Bloomberg’s Markets Live team, which also runs an MLIV Blog on the terminal. Simon White is a macro strategist who writes for the MLIV blog and also has his own MacroScope column, a wide-angled take on the most important macro and market topics, rising above the short-term noise to get the big picture. To subscribe to the MacroScope column, click here.

Tune in to MLIV at 2:45pm New York time on Wednesday June 14 for an Instant MLIV Pulse survey on the terminal after the Federal Reserve rate decision.