Washington’s hostile political factions quickly took up Fitch Ratings’ downgrade of US government debt as a new weapon of political combat — highlighting in part why the firm stripped the US of its top-tier credit rating.

Democrats and Republicans on Wednesday traded blame for the downgrade, with a group of hard-right conservatives promising to dig in during a looming spending fight that could shut down the federal government as soon as Oct. 1.

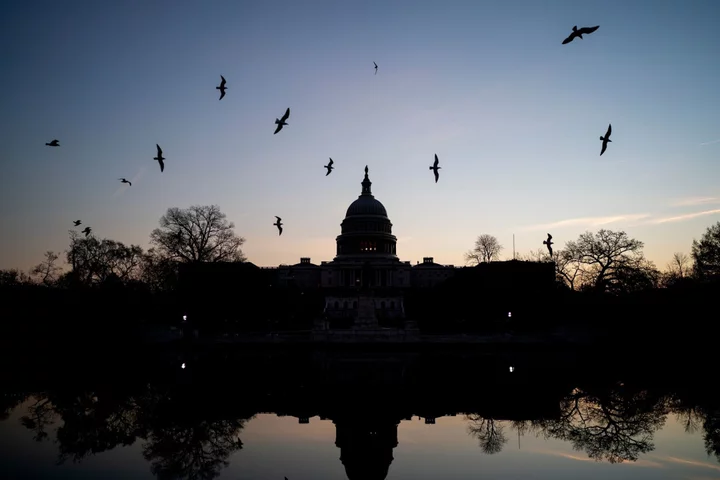

The bitter recriminations echoed the concerns raised by Fitch in announcing its decision after the close of financial markets on Tuesday. In a statement, Fitch cited an “erosion of governance relative to ‘AA’ and ‘AAA’ rated peers over the last two decades that has manifested in repeated debt limit standoffs and last-minute resolutions.”

President Joe Biden, who has spent the summer promoting his “Bidenomics” agenda as the US economy shows surprising strength, was privately frustrated over the Fitch decision and expressed irritation to his team, according to people familiar with the matter who requested anonymity to describe private conversations.

Biden learned about the decision Monday and discussed it with aides the following day. When news broke Tuesday evening, he left for dinner at a nearby seafood restaurant and a screening of Oppenheimer, a movie about the atomic bomb, leaving aides to help shape the response.

Progress on jobs, real wages and bringing down inflation — all heading in the right direction — typically matter more to voters than a Wall Street credit grader’s score. Still, any indicator pointing to shortfalls in stewardship of the economy could damage public perceptions of Biden as he seeks reelection.

Bloomberg Economics: Markets to Fitch - We Know. US Debt Primer

The president didn’t comment Wednesday when asked about Fitch’s decision during a bike ride near Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, where he is vacationing with family.

Republicans blamed the decision on Biden’s policies, saying spending on domestic programs is fueling the national debt. The right-wing House Freedom Caucus portrayed it as further reason to demand lower spending levels during the coming shutdown fight.

“It’s time to end Washington’s addiction to spending, and we have an opportunity to begin that during the appropriations process,” the group of Republican lawmakers said Wednesday in response to the downgrade.

Markets mostly shrugged off the downgrade, with Treasury yields initially falling in Asian futures markets after its announcement. On Wednesday, bond investors pushed up Treasury yields, spooked by plans for a flood of government-debt issuance and data suggesting US companies added more jobs than expected in July.

Read more: Fitch Downgrade No Shock as Treasury Coupon Auctions Increase

Biden’s team blamed Donald Trump for the ratings cut, calling it a reaction to the former president’s reckless actions in office, including efforts to overturn the 2020 election. Administration officials said Fitch’s staff in discussions ahead of the announcement repeatedly cited concerns about the effect of the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the US Capitol on Washington’s ability to govern.

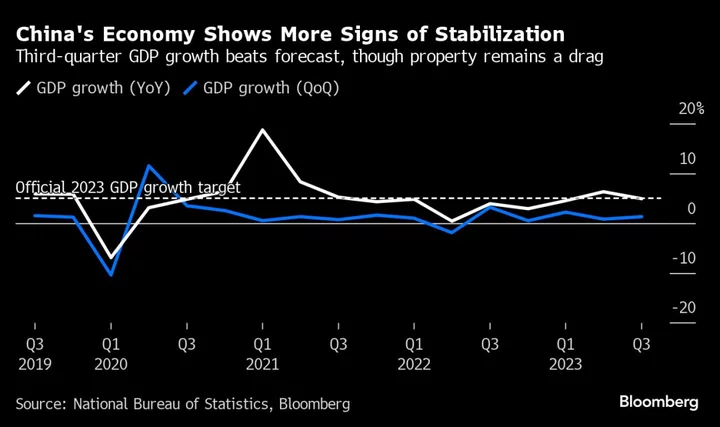

US officials also questioned the timing of Fitch’s decision, which came months after policymakers averted a debt default and more than two years since the insurrection. Gross domestic product growth, a strong jobs market and cooling inflation has caused many economists to pull back on recession predictions.

Read more: Fitch Move Spotlights US Debt Risk as Recession Fear Fades

Yet the downgrade implicitly suggests Fitch sees a good chance Trump wins back the White House in next year’s election, a seismic event that would inflame partisan divisions.

“Fitch seems to be punishing the cleanup crew, when the guy who wrecked the room is long gone,” White House Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Jared Bernstein said Wednesday on CNBC.

Taken together, the partisan rancor unleashed in the response to the ratings cut puts a grand bargain over long-term fiscal issues — already a pipe dream — even further out of reach.

“It will amplify an already polarized conversation — domestically and to a lesser extent, internationally,” said Mohamed El-Erian, chief economic adviser at Allianz SE and a Bloomberg Opinion columnist.

The Fitch downgrade was more about politics than the soundness of the US economy, said Ian Shepherdson, chief economist of Pantheon Macroeconomics.

“This is not an argument that the US won’t be able to make payments,” he said. “The point they’re making is more about governance issues. It’s the potential risk that you’ll get your payments late.”

Congress has shown little interest in tackling federal revenue levels, or righting long-term funding imbalances for Social Security and Medicare.

While Fitch’s decision has thus far had minimal impact on the short-term cost of borrowing for the US government, it will likely inflame the fight over government funding levels for next fiscal year.

Conservative Representative Chip Roy blasted “swamp and corporate cronies” for the downgrade and said he would fight a “rubber-stamping of the debt.”

Read More: Fitch’s US Credit Downgrade Sparks Criticism Along With Unease

The House and Senate are taking conflicting paths in setting discretionary spending levels despite an agreement between Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy to set an $1.59 trillion cap for fiscal 2024, cutting $12 billion from the current fiscal year, as part of deal to suspend the debt limit.

Bowing to pressure from conservatives, McCarthy has crafted spending bills with a top line of $1.47 trillion. To reach those cuts while appeasing moderates, leadership is using a series of budget gimmicks to bring down spending levels. Hard-line conservatives say they will not support that tactic and McCarthy was forced to pull an agriculture spending bill from the floor last week amid the dispute.

But in the Senate, there is bipartisan agreement to use budget moves to bring the effective spending level to $1.68 trillion, an $89 billion increase above the cap. It will be difficult for the chambers to bridge the divide, given pressure from conservatives.

“I worry it is going to inflame the chances of a shutdown and prove Fitch right,” said Marc Goldwein of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a watchdog group.

--With assistance from Christopher Condon and Katia Dmitrieva.

Author: Jordan Fabian, Erik Wasson and Jennifer Jacobs