Anyone who spends time following American politics is bound to encounter reports about polling.

Done right, it can be valuable to figure out what's motivating voters and which candidates are resonating. Done wrong, it's misleading and counterproductive.

That's why for this newsletter I end up talking a lot to Jennifer Agiesta, CNN's director of polling and election analytics, about which surveys meet CNN's standards and how I can use them correctly.

With the 2024 election just around the corner, it seemed like a good time to ask for her tips on what to look out for and avoid as the industry adapts to the changing ways Americans live and communicate. Our conversation, conducted by email, is below.

Has polling missed the mark recently?

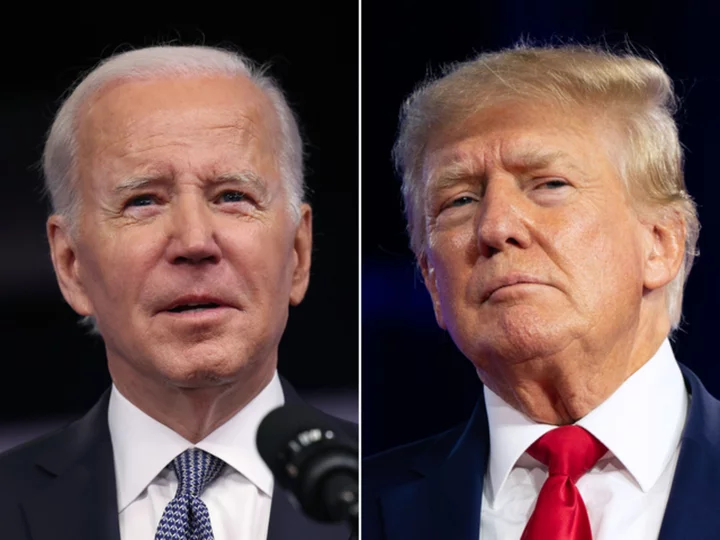

WOLF: My impression is that polling seemed to miss the rise of Donald Trump in 2016 and then missed the power of Democrats at the national level in 2022. What's the truth?

AGIESTA: In both 2022 and 2016, I would say that polling -- when you lump it all together -- had a mixed track record. Methodologically sound polling -- assessed separately from the whole slew of polls out there -- did better.

In 2022 especially, many polls actually had an excellent year: National generic ballot polling on the House of Representatives from high-quality pollsters found a close race with a slight Republican edge, which is exactly what happened, and in state polls, those that were methodologically sound had a great track record in competitive races.

Our CNN state polls in five key Senate battlegrounds, for example, had an average error of less than a point when comparing our candidate estimates to the final vote tally, and across five contested gubernatorial races we had an average error of less than a point and a half.

But there were quite a few partisan-tinged polls that tilted some of the poll averages and perhaps skewed the story of what the "polls" were showing.

In 2016, you probably remember the big takeaway that the national polls were actually quite accurate and the bigger issues happened in state polling.

Some of that was because more methodologically sound work was happening at the national level, and many state polls were not adjusting ("weighting" is the survey research term for this type of adjustment) polls for the education level of their respondents.

Those with more formal education are more likely to take polls, and with an electorate newly divided by education in the Trump era, those polls that didn't adjust for it tended to overrepresent those with college degrees who were less likely to back Donald Trump.

You add to that evidence of late shifts in the race and extremely close contests and a good amount of that polling in key states did not paint an accurate picture (the polling industry's assessment of the 2016 issues is here). Most state polling now does adjust for education.

What does CNN do to ensure its polls are sound?

WOLF: How, generally, does CNN conduct its polling?

AGIESTA: CNN has recently made changes to the way we conduct our polling to be more in line with the way people communicate today, using several different methodologies depending on the type of work we're doing.

A few times a year, we conduct surveys with 1,500 to 2,000 respondents who are sampled from a list of residential addresses in the United States. We initially contact those respondents through a mailing, which invites them to take the survey either online or by phone, depending on their preference and at their convenience, and then we follow up with an additional reminder mailing and some phone outreach to people in the sample who are members of groups that tend to be a bit harder to reach.

These polls stay in the field for almost a month. This process allows us to get higher response rates and to obtain a methodologically sound estimate of some baseline political measures for which there aren't independent, national benchmarks such as partisanship and ideology.

We also conduct polling that samples from a panel of people who have signed up to take surveys, but who were initially recruited using scientific sampling methods, which helps to protect against some of the biases that can be present in panels where anyone can sign up.

Our panel-based polls can be conducted online, by phone or by text message depending on how quickly we're trying to field and how complicated the subject matter is.

How to know when to trust a poll

WOLF: What are the signs you look for in a good poll and what are some of the polling red flags?

AGIESTA: It can be really hard for people who aren't well-versed in survey methodology to tell the difference between polls that are worth their attention and those that are not.

Pollsters are using many different methodologies to collect data, and there isn't one right way to do a good poll.

But there are a few key indicators to look for, with the first being transparency. If you can't find information about the basics of a poll -- who paid for it, what questions were asked (the full wording, not just the short description someone put in a graphic), how surveys were collected, how many people were surveyed, etc. -- then chances are it's not a very good poll.

Most reputable pollsters will gladly share that kind of information, and it's a pretty standard practice within the industry to do so.

Second, consider the source, much as you would with any other piece of information.

Gallup and Pew, for example, are known for their methodological expertise and long histories of independent, thoughtful research. Chances are pretty good that most anything they release is going to be based in solid science.

Likewise, most academic survey centers and many pollsters from independent media are taking the right steps to be methodologically sound.

But a pollster with no track record and fuzzy details on methodology, I'd probably pass.

I would also say to take campaign polling with a grain of salt. Campaigns generally only release polls when it serves their interest, so I'd be wary of those numbers.

In the same vein, market research that's publicly released that seems to prove the need for a specific product or service -- a mattress company releasing a poll that says Americans aren't getting great sleep, for example -- maybe don't take that one too seriously either.

Polling the primaries is especially hard

WOLF: The coming primary season offers its own set of challenges because there are polls focused on specific early contest states like Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina. Do you have any advice regarding these early contest polls in particular?

AGIESTA: Polling primary electorates is notoriously difficult. It's more difficult to identify likely voters, because they tend to be fairly low turnout contests, the rules on who can and can't participate are different from state to state, and the quality of voter lists that pollsters may use for sampling varies by state.

On top of that, as the election gets closer, the field of candidates and the contours of the race may change just before a contest happens -- remember how the Democratic field shrank dramatically in the two days between the South Carolina primary and Super Tuesday in 2020 as an example.

So when you're looking at primary polling, it is very important to remember that polls are snapshots in time and not necessarily great predictors of future events.

Beware the horse-race numbers

WOLF: Most of what general consumers like me want to see from a poll is which candidate is ahead. But I've heard you caution against focusing on the horse-race aspect of polling. Why?

AGIESTA: There are several reasons for that caution.

First is that polling of any kind has an error margin due to sampling. Even the most accurate poll has the possibility of some noise built into it because any sample will not be a perfect measure of the larger pool it's drawn from.

Because of that, any race that's closer than something like a 5-point margin will mostly just look like a close race in polls.

The value of polling in that situation is twofold: What it can tell you about why a race is close or what advantages each candidate has, and once you have multiple polls with similar methodologies, you can start to get a sense of how a race is trending.

Polling is great for measuring which issues are more important to voters, how enthusiastic different segments of the electorate are, and what people think about the candidates in terms of their personal traits or job performance. Those measures can tell you a lot about the state of a race that you can't get solely from a horse-race measure.

How to figure out who is ahead in a race

WOLF: What is the best way to track who is ahead or behind in an election?

AGIESTA: When you're looking at trends over time, there are a few tactics that can help to make sense of disparate data.

The best option is following the trend line within a single poll. If a pollster maintains the same methodology, the way a race moves or doesn't in that poll's trend line can tell you a lot about how it's shaping up.

That is sometimes hard to find though, as not every pollster conducts multiple surveys of the same race.

Another good way to measure change over time is to lean on an average of polls, though, as we learned in 2022, those averages can vary pretty widely depending on how they're handling things like multiple polls from the same pollster or whether they are including polls with a partisan lean.

Polling is not just conducted by phone

WOLF: I don't have a landline and I don't answer my phone for strange numbers. What makes us think polling is reaching a wide enough range of people?

AGIESTA: Many polls these days are conducted using methods other than phone.

Looking over the 13 different pollsters who released surveys that meet CNN's standards for reporting in May or June on Joe Biden's approval rating, only six conducted their surveys entirely by phone. And those phone pollsters are calling far more cellphones than landlines.

The most important thing for any poll, regardless of how it's conducted, is that it reaches people who are representative of those who are not answering the poll, and so far, it appears that right mix is achievable through multiple possible methodologies.

The people pollsters have trouble reaching

WOLF: Are there specific groups of people that pollsters acknowledge they have trouble reaching? What is being done to fix it?

AGIESTA: There are several demographic groups that pollsters know are frequently harder to reach than others -- younger people, those with less formal education, Black and Hispanic Americans are among the most notable -- and the prevailing theory of why 2020 election polling went awry is that some Republicans were less likely to participate in surveys than others.

Pollsters have several techniques to combat this.

Some pollsters who draw on online panels where they know the demographic and political traits of people who might participate in advance will account for this in their sampling plans.

Phone pollsters can do something similar when they use a sample drawn from a voter list that has some of that information connected to a voter's contact information.

And if a pollster really wants to dig deep on a hard-to-reach group, they can conduct an oversample to intentionally reach a larger number of people from that group to improve the statistical power of their estimates within that group.

What's next?

WOLF: What is the next big challenge facing pollsters?

AGIESTA: Well, the next election is always a good contender for the next big challenge for pollsters!

But I think the big challenge looming over all of that is making sure that we're finding the right ways to reach people and keep them engaged in research. The industry's leaders are thinking through the right ways to use tools such as text messaging, social media and AI while still producing representative, replicable work.

Elections are the attention-grabbing part of survey research, but pollsters measure attitudes and behaviors around so many parts of everyday life that our understanding of society would really suffer if survey methods fail to keep up with the way people communicate. I'm excited to see it continue to evolve.