Jeremy Fogel was a California state court judge in the early 1990s when an attorney asked him to lunch at a country club in Palo Alto. It was tradition, the lawyer explained, to extend an invitation to new arrivals.

Fogel declined. In an interview, he said that throughout his career — he was nominated to the federal bench by former President Bill Clinton — he tried to avoid situations that might give the impression he was being offered something because of his position, even if the rules allowed it.

“The thing that mattered most was that you were fair, the substance of fairness and being as impartial and conscientious as you could be,” said the 73-year-old Fogel, who testified before the Senate earlier this year in favor of ethics reforms for the US Supreme Court. “But I think appearances are important, too.”

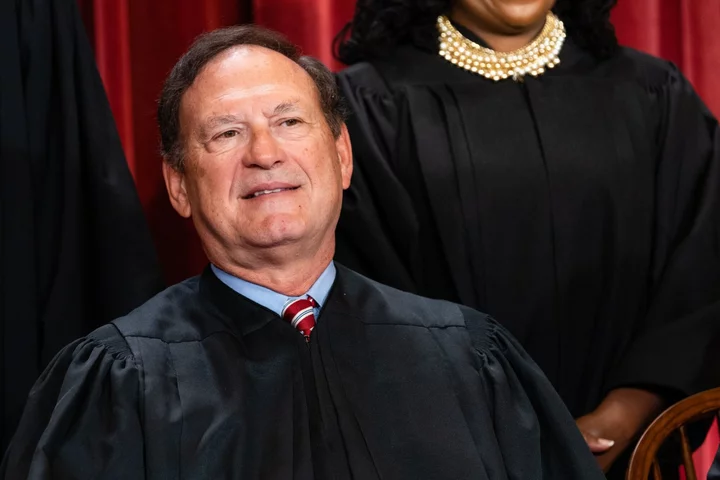

Recent controversies over perks accepted by Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito have raised questions not only about the justices’ conduct off the bench and what they disclose to the public, but also about how the judiciary broadly enforces ethics.

Fogel, who stepped down from the bench in 2018, and seven current federal judges, Republican and Democratic appointees, shared their insights into how the judiciary operates as well as their own experiences with ethics issues. They declined to comment on reports about Thomas and Alito, but most still requested anonymity given the sensitivity of addressing any situation related to the high court.

A judiciary spokesperson declined an interview request to discuss ethics compliance processes.

Golf, NBA Tickets

Some judges described taking a hard line against accepting anything of value unless it came from family or close friends – splitting the check for lunch or dinner, saying no to a golf outing with lawyers, and turning down free tickets to an NBA game. Other judges weren’t as strict, but said that before accepting a gift, even from a friend, they’d consider if it was something they could reciprocate later.

Judges said they usually found the rules clear on what to report, what gifts to refuse, and when to step down from a case. Judiciary staff and fellow judges are available to offer informal guidance, and most said that they consult the judiciary’s advisory opinions and other guidelines addressing examples of ethical quandaries.

But the judges admit there’s gray area as well. Setting aside clear conflicts of interest — like owning stock in a company appearing before them — the judges said they have discretion to decide how to comply with another core ethical principle: avoiding the “appearance” of impropriety.

One district judge, a Republican appointee, said a key factor was the nature of a relationship. The judge said they would take a trip with a friend from college or law school, but would question the motive of someone they didn’t know and whether they’d get the same offer if they weren’t a judge.

The judge said they were out for Sunday lunch with family some years ago at a Chinese restaurant and learned that another customer, a local attorney, had covered the check. While the bill likely cost no more than $75 and the lawyer didn’t have a pending case before the judge, the jurist still insisted on paying the bill.

Private Planes

Judges are allowed to accept gifts and to associate with lawyers and others who might have future business before the court. With some exceptions, they must report gifts worth more than $415 and reimbursed travel expenses. But several judges said they took a cautious approach to head off the possibility of having to recuse from cases. They noted that unlike the justices, they’re bound by a code of conduct and subject to disciplinary action.

Chief Justice John Roberts has said the justices consult the code of conduct that applies to other judges, but the high court has resisted calls to officially adopt it. Federal laws require the justices and lower court judges to file annual financial reports and to step aside from cases where their “impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”

In a report this week, ProPublica detailed an Alaska trip that Alito took in 2008, including flying on hedge fund manager Paul Singer’s private plane. The story quoted ethics experts questioning Alito’s decision not to report the trip and not to recuse from later cases involving Singer’s fund.

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, Alito said he believed the trip was “hospitality” that he wasn’t required to report at the time. The judiciary recently tightened reporting rules concerning private jet travel and free commercial lodging. Alito wrote that he wasn’t aware of Singer’s involvement in any litigation, and even if he had, he didn’t think their limited relationship would require stepping aside.

Private plane rides have cropped up in financial disclosures before. Justice Thomas reported several such trips in his reports decades ago, documents show. The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and retired Justice Stephen Breyer reported accepting free travel.

One appellate judge, a Democratic appointee, said they didn’t report a trip on a private plane several years ago. The judge said that because the ride was provided in connection with a meeting at a university where they were a trustee, they didn’t think it qualified as a gift. The university would have covered the expenses regardless, but no money changed hands, so the judge said it didn’t seem to be reportable reimbursed travel either.

In response to earlier reporting by ProPublica about undisclosed trips Thomas took with Texas billionaire Harlan Crow, Thomas released a statement saying the two men were close friends and it was personal hospitality. He said he hadn’t reported the travel on Crow’s plane and yacht after seeking advice from “colleagues and others in the judiciary.”

ProPublica’s latest story noted that a federal appeals judge in Washington, Judge A. Raymond Randolph, was on the 2008 trip with Alito, and had taken a similar excursion before. Randolph, who didn’t return a request for comment, told ProPublica that he’d contacted the judiciary’s financial disclosure office and was told by a staff member that he didn’t need to report that type of trip.

Like Randolph, several judges interviewed for this story said they had called the financial disclosure committee with questions about what to report or contacted a separate committee about ethical uncertainties.

Judge Harris Hartz, who was appointed by President George W. Bush to the 10th US Circuit Court of Appeals, said he once called the disclosure committee when he wasn’t sure how to report payments from an easement on land he owned. A staff member said there didn’t appear to be a place for it. When the judge explained that he wanted to disclose, the staffer advised him to add a note, which he did.

Hartz said in an interview that in his experience, the staff and judges on the disclosure committee do comprehensive reviews of financial reports – judges get notified about errors or missing information – and he had confidence in the system.

“The judges I know, and I know a lot of them, they’re not corrupt,” he said. “That doesn’t mean they don’t make mistakes on these forms.”