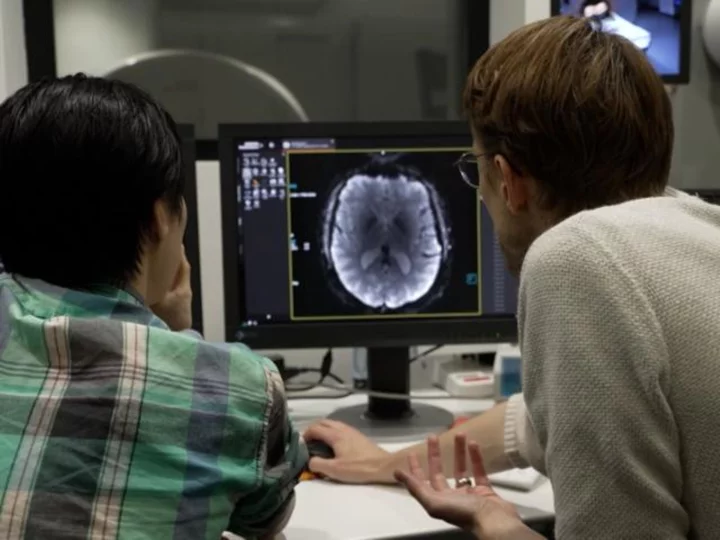

On a recent Sunday morning, I found myself in a pair of ill-fitting scrubs, lying flat on my back in the claustrophobic confines of an fMRI machine at a research facility in Austin, Texas. "The things I do for television," I thought.

Anyone who has had an MRI or fMRI scan will tell you how noisy it is — electric currents swirl creating a powerful magnetic field that produces detailed scans of your brain. On this occasion, however, I could barely hear the loud cranking of the mechanical magnets, I was given a pair of specialized earphones that began playing segments from The Wizard of Oz audiobook.

Why?

Neuroscientists at the University of Texas in Austin have figured out a way to translate scans of brain activity into words using the very same artificial intelligence technology that powers the groundbreaking chatbot ChatGPT.

The breakthrough could revolutionize how people who have lost the ability to speak can communicate. It's just one pioneering application of AI developed in recent months as the technology continues to advance and looks set to touch every part of our lives and our society.

"So, we don't like to use the term mind reading," Alexander Huth, assistant professor of neuroscience and computer science at the University of Texas at Austin, told me. "We think it conjures up things that we're actually not capable of."

Huth volunteered to be a research subject for this study, spending upward of 20 hours in the confines of an fMRI machine listening to audio clips while the machine snapped detailed pictures of his brain.

An artificial intelligence model analyzed his brain and the audio he was listening to and, over time, was eventually able to predict the words he was hearing just by watching his brain.

The researchers used the San Francisco-based startup OpenAI's first language model, GPT-1, that was developed with a massive database of books and websites. By analyzing all this data, the model learned how sentences are constructed — essentially how humans talk and think.

The researchers trained the AI to analyze the activity of Huth and other volunteers' brains while they listened to specific words. Eventually the AI learned enough that it could predict what Huth and others were listening to or watching just by monitoring their brain activity.

I spent less than a half-hour in the machine and, as expected, the AI wasn't able to decode that I had been listening to a portion of The Wizard of Oz audiobook that described Dorothy making her way along the yellow brick road.

Huth listened to the same audio but because the AI model had been trained on his brain it was accurately able to predict parts of the audio he was listening to.

While the technology is still in its infancy and shows great promise, the limitations might be a source of relief to some. AI can't easily read our minds, yet.

"The real potential application of this is in helping people who are unable to communicate," Huth explained.

He and other researchers at UT Austin believe the innovative technology could be used in the future by people with "locked-in" syndrome, stroke victims and others whose brains are functioning but are unable to speak.

"Ours is the first demonstration that we can get this level of accuracy without brain surgery. So we think that this is kind of step one along this road to actually helping people who are unable to speak without them needing to get neurosurgery," he said.

While breakthrough medical advances are no doubt good news and potentially life-changing for patients struggling with debilitating ailments, it also raises questions about how the technology could be applied in controversial settings.

Could it be used to extract a confession from a prisoner? Or to expose our deepest, darkest secrets?

The short answer, Huth and his colleagues say, is no — not at the moment.

For starters, brain scans need to occur in an fMRI machine, the AI technology needs to be trained on an individual's brain for many hours, and, according to the Texas researchers, subjects need to give their consent. If a person actively resists listening to audio or thinks about something else the brain scans will not be a success.

"We think that everyone's brain data should be kept private," said Jerry Tang, the lead author on a paper published earlier this month detailing his team's findings. "Our brains are kind of one of the final frontiers of our privacy."

Tang explained, "obviously there are concerns that brain decoding technology could be used in dangerous ways." Brain decoding is the term the researchers prefer to use instead of mind reading.

"I feel like mind reading conjures up this idea of getting at the little thoughts that you don't want to let slip, little like reactions to things. And I don't think there's any suggestion that we can really do that with this kind of approach," Huth explained. "What we can get is the big ideas that you're thinking about. The story that somebody is telling you, if you're trying to tell a story inside your head, we can kind of get at that as well."

Last week, the makers of generative AI systems, including OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, descended on Capitol Hill to testify before a Senate committee over lawmakers' concerns of the risks posed by the powerful technology. Altman warned that the development of AI without guardrails could "cause significant harm to the world" and urged lawmakers to implement regulations to address concerns.

Echoing the AI warning, Tang told CNN that lawmakers need to take "mental privacy" seriously to protect "brain data" — our thoughts — two of the more dystopian terms I've heard in the era of AI.

While the technology at the moment only works in very limited cases, that might not always be the case.

"It's important not to get a false sense of security and think that things will be this way forever," Tang warned. "Technology can improve and that could change how well we can decode and change whether decoders require a person's cooperation."