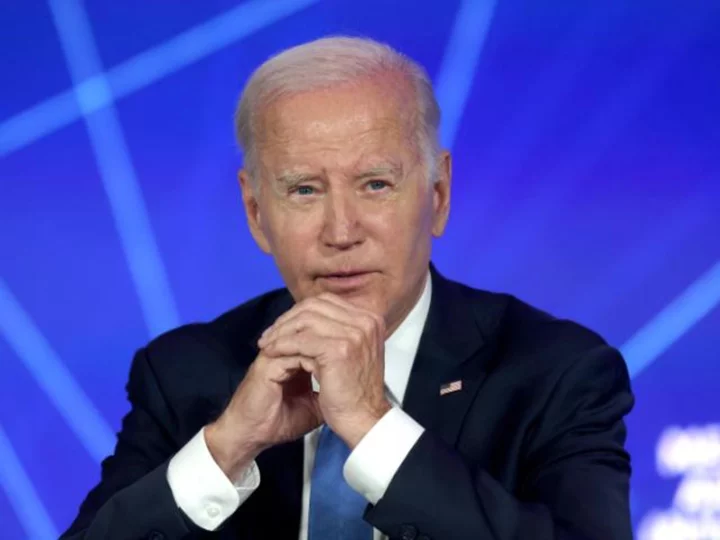

As President Joe Biden was walking from the White House residence to a briefing on the unfolding crisis in Russia, not much was certain.

It wasn't obvious, for example, how a column of Wagner group mercenaries rapidly advancing toward Moscow might affect the war in Ukraine. Nor was it clear whether Russian troops under the command of President Vladimir Putin had the will to fight them.

One thing, however, did seem apparent: whatever was happening on the M-4 highway in southern Russia had the potential to change the course of what has become a presidency-defining conflict.

Never in the sixteen months since Russia invaded Ukraine has Putin's grip on power appeared as unsteady as it did this weekend. For Biden, the moment was a reminder of how unpredictable the crisis remains, even as American officials pore over intelligence for signs that Putin's power is slipping.

Now, Biden and his team are working to make sense of the past days' events and determine what is next. The abrupt agreement brokered by Belarus to end the crisis has hardly given American officials confidence that the situation is entirely defused. If anything, it could reinforce existing doubts inside Russia about Putin's leadership, according to US officials.

"There are certainly more questions than we have answers to, at least right now. I think we'll get to the bottom of some of these but it will take months, if not years," said Steve Hall, a former CIA chief of Russia Operations.

"We know for sure now that Vladimir Putin personally, and as the leader of Russia and Russia writ large, is in a much weaker position than they were 36 hours ago," Hall said. "This is, of course, a great benefit to the Ukrainians. But I think Putin has to be diminished. There's no way he can be looked at again as a monolithic leader who controls everything inside of Russia. That's simply not the case anymore and it's obvious to everybody in the world."

Officials have long viewed the response to the war in Ukraine — specifically the remarkable show of western unity it prompted — as one of Biden's most important achievements, one they believe demonstrates a mastery of foreign policy that could serve him well in next year's election.

Yet a Ukrainian counteroffensive remains halting, and it's unclear how willing Republicans in Congress will be to approve more Ukraine aid going forward. A newly-vulnerable Putin, sitting atop the world's largest arsenal of nuclear weapons, adds fresh volatility to the mix.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken told CNN's Dana Bash on "State of the Union" Sunday: "It's too soon to tell exactly where this is going to go. And I suspect that this is a moving picture, and we haven't seen the last act yet."

"But we can say this: First of all, what we've seen is extraordinary. And I think you've seen cracks emerge that weren't there before," he added.

Officials watching events unfold late Friday and Saturday wondered how a threatened, boxed-in Putin would respond. In Biden's briefing Saturday -- convened in a small room near the White House mess hall because the Situation Room is being renovated -- officials said there were no indications Russia's nuclear posture had changed.

From Camp David, where Biden traveled shortly after, the president has been meeting with officials behind closed doors to assess what exactly happened — and what comes next.

A primary objective has been denying Putin a pretext for accusing the west of wanting him dead.

In a phone call with French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, Biden emphasized the imperative in not lending any credibility to expected claims from Putin of western interference.

The message, according to people familiar with the call, was to keep the temperature low and allow whatever was happening on the ground in Russia to play out. As Biden has told his team for months, his goal is to prevent "World War III."

A similar message went out from Washington to American embassies, who were told, if asked by their host governments, to convey "the United States has no intention of involving itself in this matter." Otherwise, the diplomatic outposts were instructed to "not pro-actively engage host government officials" on the matter, according to a person familiar with the message.

A message was also sent to the Russian government from the administration reinforcing that the US would not get involved, according to people familiar with the matter.

Biden, of course, has never been shy in his criticism of Putin. He labeled him a war criminal well before the US government made its own determination. He accused him of "genocide" in apparently unscripted remarks while standing in front of tractors in Iowa.

And at the end of a speech in Poland last year, Biden made an implicit call for regime change, saying, "For God's sake, this man cannot remain in power." His aides later sought to tamp down those comments.

Yet for all the bluster, an actual scenario where Putin no longer rules Russia has not been at the forefront of US intelligence or military planning in the 16 months since he invaded Ukraine. While aides have long debated in private the actual strength of Putin's grip on power, the prospects of ousting him have never been viewed as high, even as his "special military operation" in Ukraine has floundered badly.

If anything, the events in Russia this weekend demonstrate Putin's miscalculations in invading Ukraine in the first place, according to Democratic Rep. Elissa Slotkin of Michigan, who is a former CIA analyst.

"Putin decided to invade the entire country of Ukraine, a crazy thing to do, because he thought he could out-wait us. That American resolve, NATO resolve, our allies, we'd just get tired and bored and he could wait us out, we wouldn't want to fight a war, we wouldn't be engaged, we wouldn't stay united," Slotkin said. "A year and a half later, he's the one who's wobbling, he's the one who's exposed, he's the one who's got real problems amongst his ranks, because we've managed to keep a global coalition together to push back on him."

What White House officials had been watching closely was the internal power struggle between the Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin and the Russian Ministry of Defense. In January, the White House cited downgraded intelligence showing Wagner was becoming a "rival power center to the Russian military and other Russian militaries."

Officials suggested at the time that Prigozhin was working to advance his own interests in Ukraine instead of the broader Russian objectives.

Since then, White House and other US national security aides have been highly attuned to what one official said was an "ongoing battle" between Prigozhin and the Russian ministry of defense.

By the third week of June, US intelligence officials were confident enough in their belief that Prigozhin was planning a major challenge to Russia's military leadership that they briefed congressional leaders on the findings.

Yet the speed with which the situation escalated prompted a certain degree of scrambling. Biden's national security adviser Jake Sullivan had planned to travel this weekend to Copenhagen for talks on Ukraine, but remained stateside, joining Biden aboard Marine One for the flight to Camp David. Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley also called off planned travel overseas to attend to the situation.

At least for Biden, though, the weekend's plans remained mostly intact. He was only about an hour late for his departure to Camp David. He flew to the mountainside retreat in the Catoctin mountains with his son Hunter and Hunter's son Beau.