Arthur “Art” Gonzales didn’t appreciate how nuanced his job was until he couldn’t go to work.

In June 2020, with Covid-19 raging, a wildfire sparked up in Tonto National Forest, just north of Phoenix. A fire behavior analyst by trade, Gonzales was asked to predict the blaze’s path and pace from his home in Williams, Arizona — roughly 100 miles away. He pored over weather reports, satellite photos and videos from firefighters on the scene. But they gave him little sense of local wind speeds, nor could he ask ranchers nearby how dry the area had been lately, or how many invasive weeds were choking its gullies (the type of climate anomaly that exacerbated the devastating fire in Maui).

“I was just refreshing my computer and watching this huge column of smoke grow,” Gonzales says. “The fire had everything going for it. It completed the triangle — fuel, weather and topography.”

Eventually, Gonzales advised the sheriff to evacuate Tonto Basin, a town of about 1,700 people in the fire’s path. That’s never an easy order, he says, but it’s an increasingly common one as migration into rural swaths of the American West intersects with climate change and drought. The US Forest Service estimates some 72,000 US communities are now at risk of wildfire.

“It’s hard to think of a community anymore that’s not at risk,” Gonzales says. “If all we ever did was go out and put a fire out, that would be one thing … but when you bring in that human element, it makes this so much more challenging.”

Over the past decade, just about every aspect of analyzing wildfire behavior has grown more challenging. Climate change and the volatile weather it conflagrates are kicking up larger, faster and less predictable wildfires, leaving firefighters and analysts like Gonzales facing blazes bigger and stranger than any they’ve encountered before. In a job that rewards experience and institutional knowledge above all else, even that acumen is starting to fall short.

“It seems like every fire I go on now is outside of the norm,” Gonzales says. “We’re going to fires every year that may not have happened before.”

A longer fire season

Federal and state governments in the US employ about 224 fire behavior analysts, who are generally spread across the country with some geographic overlap. At the federal level, salaries range from $69,000 to $128,000, though overtime is standard when analysts are working 12- to 16-hour days on an active fire. Sometimes there’s also hazard pay.

Every fire behavior analyst has been busy over the past decade, but Gonzales — tucked between Las Vegas and Phoenix — is effectively on the climate front lines. A natural desert, the region is getting hotter and drier faster than much of the US.

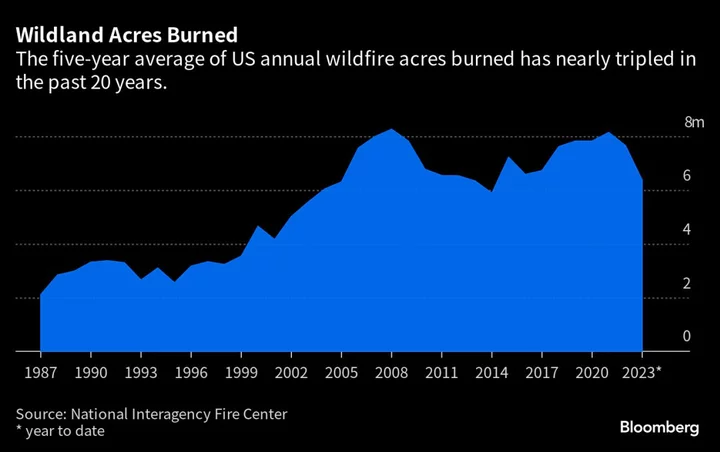

This year’s relatively slow US fire season was an anomaly: Over the past five years, an average of 7.65 million US acres were consumed by wildfire annually. That’s roughly equivalent to the state of Maryland burning every year, and 52% higher than the tally 20 years ago, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. In three of the past 10 years, more than 10 million acres burned in US wildfires, a threshold that hadn’t been passed in the prior three decades.

Science offers some explanations. Human-caused climate change is responsible for more than two thirds of the drying in the American West over the past 30 years, according to a 2021 study backed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. There’s also ample research linking hotter, drier conditions to larger and more intense wildfires.

As North America’s fire season expands from the summer into both fall and spring, it’s eating into the shoulder seasons that agencies typically used for groundwork to preclude future fires. Crews have less time to proactively clear brush and burn dangerous acreage. They also have less time to rest and recover, which exacerbates mental health issues and professional turnover.

“What was once limited to certain months now encompasses an entire ‘fire year,’” Jeffrey Rupert, director of the federal Office of Wildland Fire, told Congress in June. “This increasingly complex wildland fire environment requires a professional workforce that is positioned to meet these needs year-round.”

The firefighting playbook

Like many in the senior ranks of a wildfire career, Gonzales, now 47, started as hotshot — catch-all terminology for low-level grunts who work closest to a blaze and cut trees, whack away brush and burn areas in advance. An Arizona native, Gonzales entered the field in 1995 after attending a community college job fair at 18 years old, eager for outdoor adventure.

Hotshotting was dangerous work, but also fairly predictable: Wildfires would spark up in late spring and simmer down in the fall as cooler temperatures and precipitation snuffed them out. Over time, Gonzales built a mental catalog of how fires behave in certain situations. Wildfires, for example, travel faster uphill, as they essentially pre-heat vegetation in their path. They thrive on wind, often creating their own weather systems. And their progress varies greatly based on local trees and vegetation.

When Gonzales gets to a fire, he immediately starts building a computer model of where it’s likely to travel and how fast, generating a report known as a “fire behavior narrative.” From there, he folds in weather forecasts and historical patterns, plus observations from the field and information from locals. Occasionally, he’ll hop in a helicopter to get a closer look.

As wildfire behavior evolves, though, Gonzales’s mental library feels increasingly out of date. The American West is more populated than it used to be, its winds are more intense and its vegetation — fire fuel — is more dry and exotic. Gonzales’s models are only as good as the information he feeds them; these days he doesn’t always know just how dry the weeds are, for example, or whether they’re an invasive variety more susceptible to burning. Software used to forecast fires is likewise coming up against less predictable fire behavior.

“Sometimes we’ve got to push models to the extreme,” Gonzales says, “We’re getting outputs that someone 10 or 20 years ago would say, ‘There’s no way. It’s not going to get this big. It’s not going to get this hot.’”

Gonzales’ first year in the field, the largest fire he encountered covered 300 acres. This past June, he deployed to a fire in Alberta (along with crews from as far away as New Zealand) that covered roughly 2 million acres, double the size of Rhode Island.

The scale of firefighting operations is expanding in lockstep. These days, Gonzales is often one of several analysts assigned to a blaze, briefing layers of commanders who are themselves directing armies of firefighters from different agencies, states and even countries. As the fires get angrier, Gonzales finds himself spending more time liaising with community leaders, utilities, highway departments and other agencies impacted by them.

He says the work is both professionally stressful and personally — existentially — dispiriting. Gonzales spends most of his free time in the woods, and it pains him to see them ravaged. “The last several years, it’s been so active; it’s all-consuming,” he says. “It’s disheartening to see us lose complete ecosystems. But what really weighs on me is the pace at which we’re seeing these larger fires.”

“A massive safety issue”

The stress of the job, plus its relatively low pay, has sparked something of a labor crisis in US wildfire fighting. That’s in part because a system that worked decently when wildfires were seasonal and predictable is struggling to adapt to a world in which they aren’t. Federal agencies, which have the purview to combat fire most broadly, are already losing professionals to safer and more stable jobs, including better-paying state positions. Over the past three years, almost half of full-time US federal wildland firefighters have left their jobs.

The turnover would no doubt be higher if it wasn’t for a recent 20% pay bump, though that sweetener will expire next month without congressional action. If pay raises aren’t made permanent, the National Federation of Federal Employees estimates between 30% and 50% of federal wildland firefighters will resign.

“Honestly, the seasonal jobs tend to go a bit better, because a lot of college kids are interested,” says Cardell Johnson, director of the natural resources and environment team at the Government Accountability Office. “They go back to the semester having earned $10,000 in a summer.”

In a bit of a vicious cycle, the turnover is making for greener crews, just as climate change is supercharging fires. It’s a “massive safety issue,” says Tim Casperson, a former wildfire fighter who covers the trade in his newsletter, The Hot Shot Wake Up. “It’s like throwing a first-year infantry person in with special forces in Afghanistan.”

For Gonzales, being a tenured fire behavior analyst now means deploying further afield and staying longer on any given blaze. Last year, he spent 70 days in the field on five separate fires, more than almost any other analyst in the country. This summer was less busy, but he spent 20 days of it on a monster fire in Canada.

In September, Gonzales finally got home, dropped his pack, shouldered another one and headed back into the forest — this time one that wasn’t burning. He tried to lure elk within range of his bow and arrows, but there was a huge acorn crop this year, so the animals were more interested in eating than mating. When the elk didn’t show, he used his binoculars to scan for birds.

The respite was short. The mellow fire season in the lower 48 has created perfect conditions for prescribed burns and other proactive mitigation this fall. And for now, there are plenty of idle firefighters available — an increasingly rare luxury. “Nobody pushes pause, where you can go away for two or three weeks,” Gonzales says. “There’s hardly a time anymore when nothing is going on.”