Digging up the metals that go into power grids and electric cars is crucial to the energy transition. While the mining industry has plenty of reserves to tap, it faces a worrying shortage of young workers needed to get materials out of the ground.

In regions like Canada and the US, enrollment or graduation from university courses related to mining engineering slipped in recent years. The dilemma adds to the challenges miners face as they scramble to boost output of everything from copper and nickel to cobalt and lithium, just as many nations view supplies as a matter of national security and users rush to secure metal.

Fewer students want to be geologists or engineers, partly due to mining’s negative image regarding pollution, human rights and gender equality. That’s leaving the industry with an aging workforce and forcing it to recruit from outside the traditional university talent pool, such as through apprenticeship programs and internal training.

“There’s been a bit of a lost decade in people going through university in mining courses — that’s proving to really come to crunch point now,” said Alison Allen, deputy managing director at UK-based mining consultancy Wardell Armstrong. “There are too few graduates filling needs.”

The waning interest is clear in some of the world’s key mining jurisdictions. At the Colorado School of Mines, total enrollment in mining, geophysical and geological engineering undergraduate degree courses last year was down about 35% from almost a decade ago. In Canada, mining and mineral engineering graduates dropped by a third between 2016 and 2020, according to Statistics Canada data.

It’s a similar story at the UK’s prestigious Camborne School of Mines, traditionally an important feeder school for the global industry. The number earning degrees from its undergraduate mining engineering course fell in recent years, with new intakes halted in 2020. The school this year announced new programs for mining employees.

UK mining faces a big challenge to meet its needs, according to Rhys Morgan, an engineering and education director at the Royal Academy of Engineering. Some 80% of the 1,250 mining engineers registered with the UK’s Engineering Council are over 50, and 40% are at least 60, he said.

There are already major labor shortages in American mining, leading to significant cost increases, Walter Copan, a vice president at the Colorado School of Mines, said in June.

Attracting Talent

Efforts to tackle graduate shortages include new routes into work and in-house training. For example, Wardell Armstrong says the industry has opened apprenticeship positions to help fill some technician and junior roles.

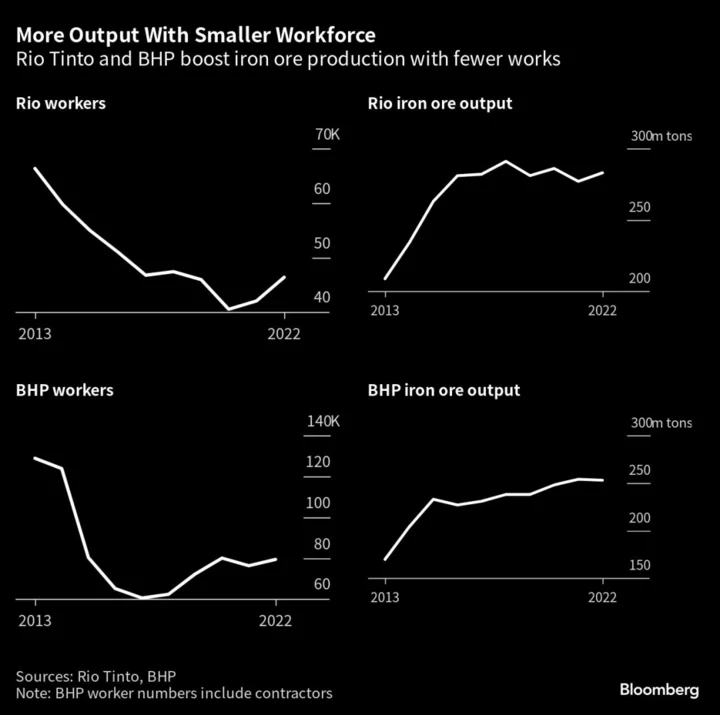

Coping with fewer workers isn’t new. More efficient output means heavyweights BHP Group and Rio Tinto Group are producing much more iron ore than a decade ago — with a lot fewer workers. AI and automation may further reduce the sector’s reliance on skilled labor, and Rio’s tech graduate roles rose 15% this year.

There’s also a need for more non-engineering jobs, particularly with sustainability and social issues increasingly in the spotlight. Anglo American Plc says its focus is shifting to include graduates with degrees in social and environmental sciences and data analytics.

Plus, companies can get greater access to better interest rates and finance if they can prove their ESG standing, Wardell Armstrong’s Allen said.

Job Prospects

The drop in mining graduates means that those who do choose to go into the industry have a chance of a lucrative career.

“I was bluntly told that if I have a master’s at CSM, I could walk into a job,” said Michael Dinata, who’s finishing a master’s course at the Camborne School of Mines after studying politics. Yet he’s found some people are surprised at his choice, given the stigma surrounding mining.

“I found that ironic, because the entire infrastructure of technology is built on metal,” he said.

Enticing more students could be crucial to avoiding a potential shortage of new geologists and engineers in the coming years and decades. Legislation was introduced in the US this year that would provide grants to help mining schools tackle declining enrollment.

“There is a very challenging market competing for engineering skills,” the Royal Academy of Engineering’s Morgan said. “A fresh supply of new talent is critical to mine the materials that will enable the successful transition to electrification to meet net-zero ambitions.”