As night fell in Marrakech earlier this month, Christine Lagarde was there, busy talking to a colleague from back in Frankfurt.

For about an hour one evening until 9 p.m., as cool air wafted through the Moroccan city, the European Central Bank president sat under the stars with Bank of France Governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau, perched near a carpet exhibit at the International Monetary Fund’s meetings.

Click here for a German version of this story. Subscribe to our daily German newsletter.

Whether or not they discussed the close-run Sept. 14 decision to raise interest rates — one he was unenthusiastic about — isn’t clear, but the encounter itself is typical of her one-on-one approach to engaging with her 25 Governing Council peers. Investing such time and energy, after four exhausting years in office, will remain critical as her reign enters a tense phase.

The public message Lagarde communicated the next day was gloomy, warning that rate hikes are tightening financial conditions “like it has never happened before” — and that she and colleagues are juggling several such “balls in the air.”

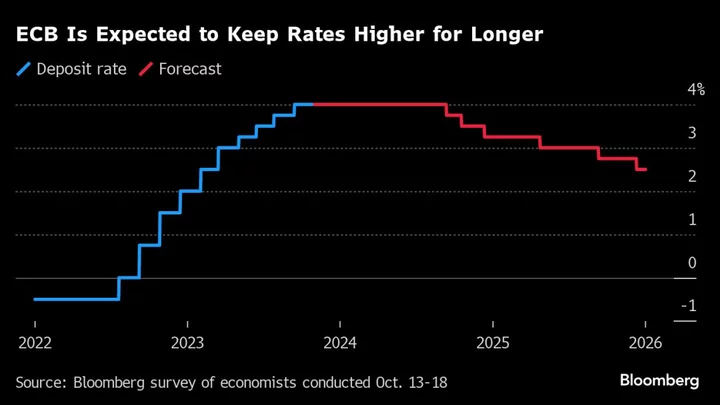

The ECB confirmed on Thursday that after an unprecedented campaign to raise borrowing costs, it plans to maintain the squeeze on the euro area for an extended period.

With inflation too high, output shrinking or barely growing, a fiscal squeeze looming, key elections due, and wars raging nearby, the confluence of political and economic cycles puts the president at the fore of scrutiny on the central bank.

Holding to the high-for-longer mantra of global policy, Lagarde will need to shift the gears of an unwieldy institution from activism to alertness. Meanwhile she knows the independent ECB is fair game for politicians — having served as finance minister in a government that tried to interfere with it.

“Leading a central bank and a finance ministry each present their own unique challenges,” US Treasury Secretary and former Federal Reserve chief Janet Yellen told Bloomberg, adding that she’s “honored” to call Lagarde a friend and colleague. “Neither job is easy, particularly in the midst of a global pandemic and the resulting economic dislocation, or a financial crisis that spills across borders.”

Insights into how Lagarde will navigate public challenges and corral restless colleagues were shared by multiple officials, many speaking on condition of anonymity because ECB deliberations are confidential.

Most agreed that the president, at the halfway mark of her term, faces a fraught time even after years of fighting crises and inflation. That’s on top of climate change, reordering supply chains and an aging society.

Keeping her peers focused is likely to fully occupy Lagarde. While she has achieved more public discipline than her predecessor Mario Draghi — whose style of doing things his own way alienated those with different views — it’s hard going.

The president has managed that by putting herself at the nexus of dialog between officials, regularly speaking to them individually — by phone, over coffee, visiting a museum together or even playing golf.

“Lagarde strives to have consensus, and she’s willing to spend quite some time brokering it,” said Governing Council member Yannis Stournaras.

Officials cite her charm in such moments, punctuated by smiles, hugs and listening. It works well, but it takes effort.

Those discussions let her take the mood, ensuring the decision proposals she and her chief economist, Philip Lane, prepare in close cooperation are reflecting what can realistically be agreed.

In ECB meetings, Lagarde actively encourages colleagues to pay attention. But officials also cite occasions when her style can grate: She once told them to stop looking at phones, and on another recent occasion, collected up devices to prevent leaks.

Overall, there’s recognition that her approach exudes authority while ensuring everyone gets their say. She has also instilled more team spirit into a group whose grumbling about Draghi in 2019 was barely contained.

The hard-fought outcome of the ECB’s September meeting was the first under Lagarde to draw comparisons with then, underscoring how her work will be cut out to keep order.

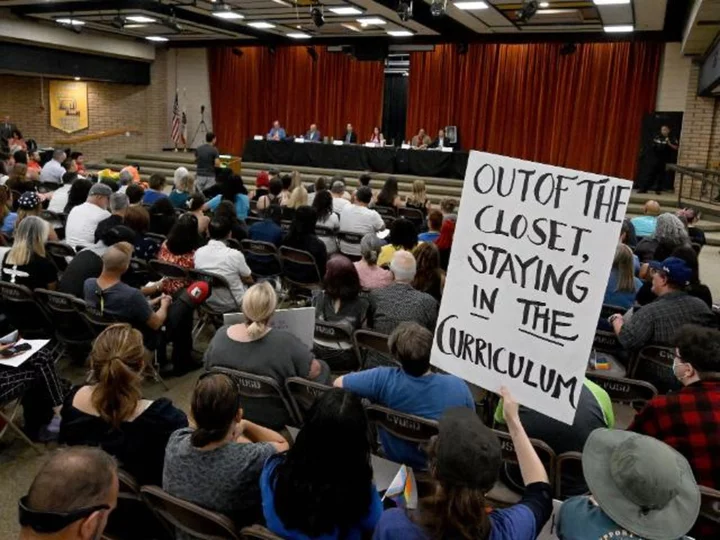

Politics outside the room won’t help the president, who as the chief protagonist of policy will bear the most responsibility.

Blaming the ECB for persistent inflation, faltering economies or high borrowing costs is likely to be a constant temptation before European Parliament elections in June.

In Italy it’s already normal discourse. Premier Giorgia Meloni did that on Oct. 17, complaining that higher rates are constraining her budget.

Political heat is ratcheting up elsewhere too. When finance ministers met in Spain after the Sept. 14 rate increase, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire declared: “enough is enough.”

Inside the gathering, and in the presence of Lagarde, he and his German counterpart, Christian Lindner, warned that cost-of-living worries could propel extremist parties.

Germany itself faces a pivotal year, with September elections in three eastern states where the populist Alternative for Germany may win. Inflation there peaked above 11% a year ago, but griping media led by tabloid Bild already targeted Lagarde as prices started to surge.

She knows only too well the political benefits of kicking the ECB. Former French President Nicolas Sarkozy repeatedly criticized its policies when in office, and even challenged its independence.

As his finance minister, Lagarde sometimes offered her own commentary. In December 2008, three months after Lehman Brothers collapsed, she said officials hadn’t “done badly,” though “on occasion we wished they had gone just a little quicker.” A few weeks later she observed that “I’m confident the ECB will appreciate inflation is under control and that growth is key.”

Lagarde was in another job, but that backstory gives her an understanding of the challenges faced by politicians, even if she is a different president from the technocrat class that led the ECB until now.

“A finance minister’s agenda is broad but quite shallow,” said Slovakian Governor Peter Kazimir, who like her, previously had that job. “It’s quite an adjustment when you then find yourself at a central bank where your focus is narrow but very, very deep.”

Officials describe how she plays to her strengths, power-broking, mediating, and keeping her eye on the bigger picture, while arming herself with enough economics to communicate the ECB’s message.

Lagarde was a senior lawyer before switching to politics and then leading the IMF, but colleagues respect the breadth of her experience.

“You can be an excellent economist and destroy an economy,” said Stournaras, another former finance minister. “Judgment is the No. 1 quality.”

One of Lagarde’s advantages described by officials is that her governmental background leads her to favor pragmatism over dogma. Yellen cites her “ability to build global coalitions around complex, but deeply meaningful goals.”

A fleet-footed approach to policy has helped her through past troubles. A stumble in 2020 — her remark that the ECB is “not here to close spreads,” prompting a blowout of Italian bond yields — offered an early lesson on the power of words. She then won support for an emergency asset-purchase program within days.

When signs of stress in Italian debt markets returned in 2022, Lagarde secured agreement to create a crisis tool that contained spreads and paved the way for 10 consecutive increases in borrowing costs.

Where the ECB has endured criticism is in its delay in raising rates, held back by Lane’s insistence that inflation pressures would be transitory, and by promises to keep policy loose.

In Marrakech, Lagarde confronted that, claiming that officials shifted stance as early as December 2021 by agreeing to dial down bond purchases, even if liftoff took another seven months to arrive.

Given the unfinished business of inflation, and mounting economic fallout, the ECB remains vulnerable. Lagarde declared in September that “the difficult times are now.”

That points to a challenge in communicating to citizens and politicians, all the while ensuring that investors stay convinced the ECB will see the job through.

It’s said to be a frustration to Lagarde, who believes perception matters almost as much as actions, that the market sometimes doesn’t understand her — or doesn’t want to.

The headache of satisfying fickle investors and grumpy voters, managing needy colleagues and being unable to focus on less intense topics, sometimes makes people close to her wonder: does she really want another four years?

A possible alternative would be Brussels, succeeding Ursula von der Leyen at the top of the European Commission if that position comes up next summer.

Lagarde herself has publicly committed to staying on to 2027. That will involve some hard and ultimately lonely decisions, including timing a shift in monetary policy, perhaps whether to bail out Italy, and other gyrations of what she describes as “an age of shifts and breaks.”

In Marrakech, when asked publicly how she copes with tough times, Lagarde replied that she holds her breath. Normal people last maybe 90 seconds but using a method called apnea, she can endure 3 1/2 minutes.

“It’s a way to control your breathing, to hold it — to feel your body responding to the stress,” she said.

--With assistance from Christopher Condon, William Horobin, Eric Martin, Jorge Valero, Alexander Weber and Rodrigo Orihuela.