Giorgia Meloni’s economic policy has just taken a sharply populist turn, launching an assault on bank profits and vying to tighten its grip over corporate Italy.

The prime minister’s nine-month-old far-right coalition government is doubling down on a state-led approach to managing prosperity with a program unveiled on Monday that unsettled investors and threatened to overshadow relations with China.

Italian bank stocks plunged in the wake of the late-night decree whose 40% tax on lenders’ profits was just the most eye-catching item in a whole raft of measures.

Ministers also backed limits on transfers of technology and the creation of a new special commissioner for large foreign investments.

The package extends the Meloni alliance’s attempt at wielding power over the economy, after already instituting a changing of the guard in its own image at the Treasury, several state-owned companies and even the central bank.

It shows her determination to expand its populist agenda in the third-biggest member of the euro zone and appease the US — which she visited just last month — even at the expense of real or potential international fallout.

“In terms of popularity, I think it’s a good move,” said Wolfgango Piccoli, research director at political risk advisory Teneo in London. “It’ll fly well, especially with the constituency of the ruling coalition.”

Piccoli referred in particular to the windfall tax on banks, which wiped out about $10 billion from the market value of the country’s lenders. The decree could cost banks more than €3 billion ($3.3 billion) in taxes, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

Salvini’s Role

That the package was unveiled in public by Deputy Premier and League Leader Matteo Salvini, the most overtly populist member of the coalition, was a likely signal of messaging the government’s intent.

Politicians are prioritizing “short-term fiscal gains” over the “longer-term cost of equity for the banking sector,” Filippo Maria Alloatti, head of financials at Federated Hermes, told Bloomberg Television. “It’s not the first time and neither won’t be the last time.”

The government’s package included a measure to exercise special “golden share” powers to block technology transfers abroad in strategic sectors including artificial intelligence, production of semiconductors, cybersecurity, aerospace, and energy.

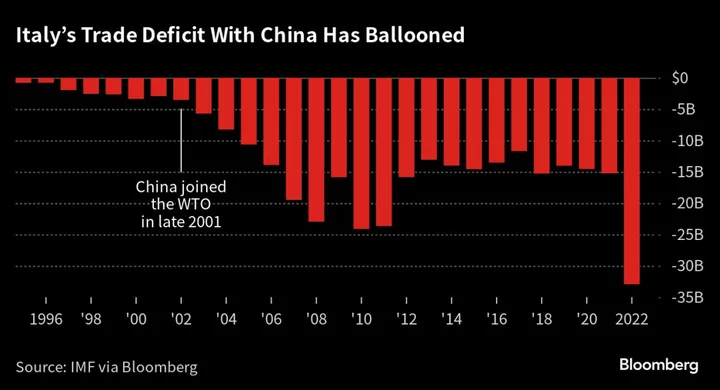

That may be a jab at China, and is in line with US pressure on Italy to move away from its Belt and Road Initiative and commercial ties with the country.

“It’s about China without mentioning China,” said Julian Ringhof, a policy fellow at the European Council for Foreign Relations in Brussels. “China realizes the mood is changing in European member states.”

Such laws exist in the US with a clear focus on stopping transfer to countries like China. The EU recently released its European Security Strategy as a new tool that also deters interaction with that nation in certain sectors, though never actually mentioning it by name.

For example, the EU urges member states to tighten export controls on technology that could be exploited by rivals and cautions not to share information with “countries of concern” that could harness AI and quantum computing for military use.

Piccoli of Teneo agreed that it’s possible to speculate that the new move reflects China concern.

“Symbolically, it’s an important exit,” he said. “In reality, not much is going to change in terms of the Italy and China relations.”

The government’s surprise legislative onslaught hit Italians at an awkward moment, with much of the country on vacation in advance of the Aug. 15 national holiday.

Even so, it still marks gear shift in the Meloni coalition’s engagement with its guardians of prosperity, after a three-stage changeover of the economic elite as the coalition took advantage of opportune timing of several job terms ending concurrently.

That began with the installation of new Treasury officials earlier this year and continued with selections of state enterprise chiefs in recent months. Then in June, the government picked ECB Executive Board member Fabio Panetta as the next chief of the Bank of Italy.

By confronting the country’s lenders however, the possibility of more impact — and the corresponding risk of damage — is greater than the government’s prior moves to remodel Italy, not least at a time when the economy has begun to contract.

“In theory they could say, OK you know what, we’re going to lend less to the real economy,” said Alloatti of Federated Hermes. “This, I think, is a possibility, in order to retain more earnings.”