(Bloomberg) --

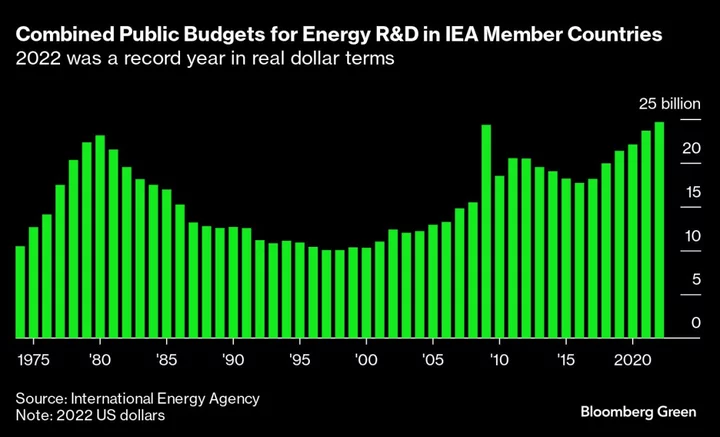

Since the International Energy Agency was founded five decades ago, it has compiled data on the government research and development budgets devoted to energy in its 31 member countries. This lets us take a detailed look at how energy-conscious developed countries have prioritized research over time.

The IEA’s data series begins in 1974, during the first oil price shock. The numbers show energy R&D doubling from 1974 to 1980 and then falling steadily for more than a decade as oil prices tumbled and remained low. R&D begins rising again after the year 2000. And at that point, a couple of factors take hold.

The first is not just rising oil prices, but rising energy and commodity prices in general, spiking just before the global financial crisis in 2008. The second is renewed government interest in sponsoring energy research and innovation, both during the recovery from the Great Recession and again during the later 2010s and into the 2020s. In real dollar terms, IEA member countries now allocate more money to energy R&D than they have at any point in the past 50 years.

(If you’re wondering why 2009 is such a distinct outlier in the chart above, it’s the year the US government devoted $16 billion to public energy R&D as part of the American Recovery and Re-investment Act. Needless to say, that outlay has not been repeated since.)

Just as important as the topline figures are the changes in R&D budgets for specific technologies or groups of technologies over time.

For almost the entire period covered by the data set, nuclear energy has received the most R&D budget of any technology. It began with nearly $8 billion of annual public R&D in the mid-1970s, a figure that would rise by more than half again through the early 1980s. Since then, however, the nuclear budget has fallen significantly, back into the range of $4 billion to $5 billion from the mid-1990s onward. Its budget is increasing again, but still well below where it was almost 50 years ago.

Renewable energy, like nuclear power, saw growing research budgets through the 1970s and a similar peak in the early 1980s. The total then fell back below $1 billion in 1986 and only twice exceeded $1 billion until 2002. It then rose steadily before receiving a huge boost in 2009, thanks to the US, and has remained in the range of $3 billion since 2014.

Energy efficiency, which received all of $300 million in public research and development funding in 1973, follows a different pattern. Unlike nuclear or renewables, its budget has grown steadily almost every year, though it too experienced a mid-1980s lull. Having tripled from less than $2 billion at the start of the century to $6 billion in 2021, efficiency is now the single largest recipient of IEA member countries’ energy R&D budgets.

There are a few other patterns worth noting in the data. The first is fossil fuel R&D funding, which like nuclear peaked in the 1970s (with the exception, again, of that spike in 2009). This budget includes research into carbon capture and storage, so it will be worth watching how this figure changes over time with new government commitments to CCS.

The second is R&D into “cross-cutting technologies” that combine efforts in more than one sector. This group received $985 million (9% of the total budget) in 1974, and almost $3.9 billion (or 15% of the total) last year.

Finally, there is hydrogen. It doesn’t even show up as an IEA member-state line item until 2002, when it received just $57 million. Funding is growing in leaps, though: It reached $1 billion in 2005, slowly declined to less than $500 million in 2015 and then reached almost $1.4 billion in 2021 and $3.1 billion in 2022. At that level, hydrogen research and development is not far behind renewable energy R&D spending. Given that global subsidies to hydrogen have quadrupled in two years, to $280 billion , it seems probable that public investment in hydrogen R&D will continue to rise.

Of all these numbers, the most important one is the most basic: $24.7 billion, the total public-sector spend by 31 IEA members on energy R&D last year. The sector composition of those dollars is worth noting, and watching, as it reflects country priorities for energy technology development and security. But it is the full volume that is most important. Every dollar devoted to fundamental research matters. Just imagine how global energy could have evolved if the research dollars of the early 1980s had continued to flow at the same level, or even higher, in the decades since.