The National Health Service is “hopeless” and needs a “complete restructuring,” says the woman behind one of its few major successes in recent years. But Kate Bingham — mastermind of the Covid vaccine roll out during Boris Johnson’s premiership — doesn’t think a Conservative government can fix the record waiting lists, chronic staff shortages and frequent strikes.

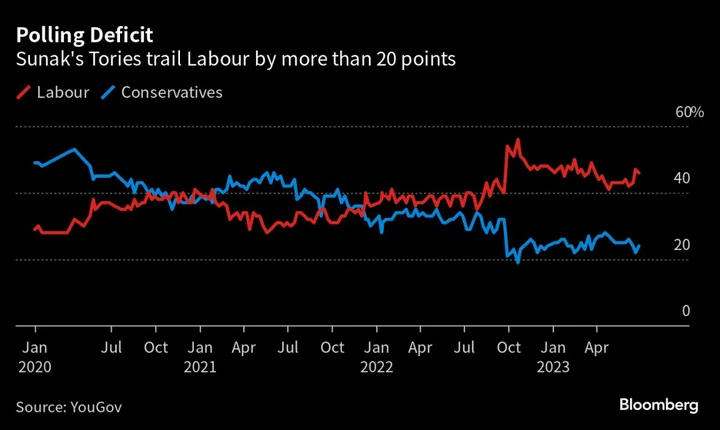

“That’s only going to happen with Labour,” says Bingham during an interview at the head office of the investment fund she runs, SV Health Investors LLP, in London. Public opinion has turned against Britain’s ruling party, she says, making reform of the NHS impossible. “If the Tories do it they’ll say they’re all privatizing it and they’re doing it to line their own pockets. That would be the mantra.”

Since Covid, Bingham, 57, has become something of an unwilling expert in the court of public opinion. An investor in life sciences for more than 30 years, she was thrown into the spotlight by a spell as head of the UK’s Vaccine Taskforce. Bingham — who is married to Conservative Member of Parliament Jesse Norman — was accused of being the face of Tory chumocracy after she was handpicked by Johnson to fill the unpaid role without an interview.

“It was miserable,” say Bingham, of the ordeal. “If you’re in the private sector, you’re not used to people taking potshots at you based on some newspaper report.” The “punchline,” says Bingham, is that “we did a really good job.”

References to Norman, who was a couple of years ahead of Johnson at Eton — Britain’s most exclusive private school — are peppered throughout our interview. On the table in front of Bingham is a birthday present for her husband — a statue of Edmund Burke that she picked up for £5,000 ($6,324) at a recent auction. “He’s a real Burke scholar,” she says.

The negative headlines were muted once it emerged that Bingham and her team had negotiated a string of deals with pharmaceutical companies — with Britain becoming the first company to approve the Pfizer Inc.-BioNTech SE jab. A framed copy of the Daily Star of Scotland, with the headline “Champagne Super Nova” sits next to her desk in London’s Holborn district. It’s in reference to Bingham’s decision to celebrate good results from a trial into Novavax Inc.’s vaccine by giving up Dry January early in 2021.

Although Bingham is now back at her day job, where she invests in companies such as Bicycle Therapeutics Plc, a $780 million biotech company listed on Nasdaq, she has continued to use her platform to push for change in Whitehall.

Funding Science

The government announced a £650 million package of measures last month to boost Britain’s life sciences sector, as part of a bid by Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt to spur economic growth. For Bingham, who’d previously argued there was a “deliberate government policy” not to support life sciences in the UK, this is a sign that ministers are “actually paying attention.”

However, problems remain. “We’ve got a wonderful science and technology department led by non-scientists,” says Bingham. “There’s no industry expert from life sciences in government, and that’s what you need.”

The UK has lost its lead after gaining ground in the early months of the pandemic, Bingham says. John Bell, regius professor of medicine at Oxford University and a government adviser, told MPs in November that the UK’s clinical research capability was “actually much much worse than it’s ever been in my living memory”.

At the same time, pharma companies are increasingly agitated by the UK’s determination to curb spending on drugs. Pascal Soriot, the head of AstraZeneca Plc, and GSK Plc chief executive officer Emma Walmsley were among bosses calling for an urgent resolution to a row over the government’s pricing system.

“We are absolutely at the bottom end of drugs budgets and there is no doubt a mentality that we need to save money at all times,” says Bingham.

AstraZeneca is building a new manufacturing plant in Ireland instead of the UK, a decision which Soriot put down to the tax regime. Bingham says Astra felt “unloved” by the government which failed to defend the Cambridge-based drug maker when it was being “beaten up” in Europe over its Covid jab.

“If I was the government, I would have my arms round them with super-glue, basically saying, ‘you are incredibly important to us, and how can we help you build your business and make it the success it can and should be’,” she says.

Oxford and Harvard

Bingham is the only daughter of the late Tom Bingham, the former lord chief justice. She was educated at the independent St. Paul’s girls’ school in west London, before reading biochemistry at Oxford. She later studied at Harvard business school, and worked at Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. and the strategy consulting firm Monitor before joining Schroder Ventures Life Sciences, then part of the larger investment fund. In 2001, the company became independent from Schroders.

A target for blame is the UK pension industry, which Bingham says is “pretty shite.” The UK is a “financial center of the world” yet pushes much of its pensions cash into bonds rather than taking on riskier equities. “We never want to pay any money for anybody ever,” she says.

Discounting strategic investors, less than 5% of the shareholders in Bingham’s funds or the companies she invests in are from the UK — most are from the US or continental Europe. “Now that’s a terrible place to be,” she says. “The other guys have got much bigger and we haven’t.”

Covid Controversies

The UK is still in the midst of an inquiry into the Covid pandemic, which has triggered a political storm — partly over the question of whether WhatsApp messages between government officials and ministers should be treated as private, or open to scrutiny. Bingham can finally see the funny side.

“Well I think Matt Hancock gave us a lot of transparency,” she says with a chuckle, in reference to the former health secretary and a stream of his Whatsapp messages leaked to the Daily Telegraph. She has just finished listening to a book about Johnson’s time in Downing Street, which came to be dominated by the pandemic. “I was shocked. I knew it was chaotic, but I didn’t know it was as bad as that.”

On top of the political fallout, the NHS is still suffering from the impact of Covid. Waiting lists that built up during the pandemic are getting worse each time front-line workers strike — this week, junior doctors are holding their latest walkout, with unions and activists railing against pay restraint and the outsourcing of services to private companies.

When the NHS marks its 75th birthday in under three weeks’ time, many Britons will not be celebrating. And many, as Bingham fears, will keep blaming the Conservative government for the state that the famous health system finds itself in.