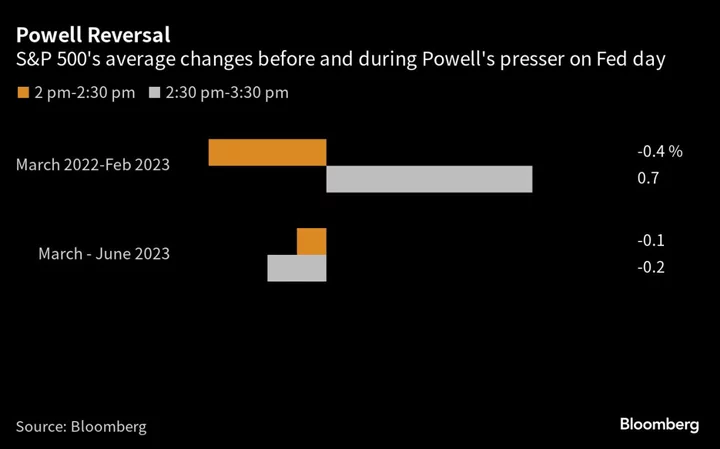

In what was a brutal 2022 for investors, there was at least one sure-fire, money-making proposition for much of the year. All they had to do was buy stocks and bonds seconds before Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell began speaking at his post-FOMC press conference and dump them as he was wrapping up.

That March, when the Fed began hiking interest rates, the stock market’s gains during this 60-minute window were spectacular: 1.6%. And then they just kept coming: 2% at the May meeting, 2% in June and 1.6% in July. Whatever Powell said, traders took it as dovish, or at least less hawkish than the FOMC statement they had just read. In February, the frenzy suddenly re-appeared. Another 1.6% stock surge. Bond gains looked similar, albeit smaller.

Now, those easy-money FOMC days appear to be over.

Strip out that February pop, and Powell’s press conferences are mostly delivering small losses of late. That’s bad news for the rapid-fire, quant-heavy shops that analysts suspect were most deftly mining the trade.

But there’s a bigger, more important message here: The wild volatility that erupted across markets at the outset of the hiking cycle is slowly disappearing. With inflation now cooling, the economy normalizing and the Fed close to ending its hikes — a quarter-point increase today and maybe another in coming months — the predictability of future rates is much greater than it was when Powell was urgently orchestrating the largest increases in decades. There’s simply less room for traders to misinterpret his comments.

“The hikes most likely are coming to an end,” said Ed Al-Hussainy, global rates strategist at Columbia Threadneedle. “So do you want to use the playbook from 2022? I wouldn’t do it. I would take my profits and hang onto them and go do something else.”

Some Theories

Plenty of criticism has been pointed at Powell for failing to clearly communicate at times the Fed’s determination to snuff out inflation. But no one really knows why traders kept bidding up assets as he spoke. Theories abound, many of them interrelated.

One has it that Powell is more dovish than the broader 12-member committee that sets rates. (Powell actually ranks as a centrist, according to a new Bloomberg survey of economists.) Or that he was framing his answers to appease the doves in the committee and keep them on his side. Another states that Powell, prompted by certain sorts of questions from reporters, kept using words — like disinflation and financial conditions — that triggered buy orders from algos.

The most popular explanation, though, is that investors simply chose to hear what they wanted to hear.

Many of them made fortunes during the bull market in stocks and bonds over the past two decades, and they long for a return to the rock-bottom interest rates that fueled those gains. So they latched onto any words, however tangential, that seemed to indicate the hiking cycle was almost over (and that rate cuts were just around the corner) even if Powell hadn’t meant to signal that at all.

“That’s some kind of confirmation bias,” said Tim Duy, chief US economist at SGH Macro Advisors. “Market participants would like this to be over. And they want to tell a dovish story to get to that point.”

The Fed is slated to release its rates decision at 2 p.m. in Washington today. Powell will take the podium a half hour later.

--With assistance from Oliver Woolf and Kosuma Kornkanitnan.