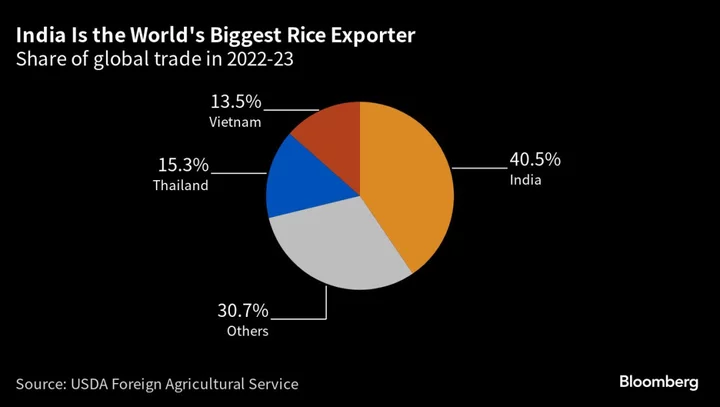

Rice prices are set to surge after top exporter India banned a large chunk of shipments, adding to stresses on global food markets that have already been roiled by bad weather and the worsening conflict in Ukraine.

“In the short term, the price is definitely going up, it’s just a question of how high up it will go,” said Chookiat Ophaswongse, honorary president of the Thai Rice Exporters Association, one of the world’s biggest shippers of the grain. “And it will be a spike, it’s not going to be increasing incrementally.”

Rice is vital to the diets of billions in Asia and Africa, and a surge in prices would add to inflationary pressures and jack up the import bills for buyers. India’s restriction, which applies to shipments of non-basmati white rice, is aimed at controlling domestic prices. The move comes as concerns escalate about the impact on farm supplies of the El Niño weather pattern, soaring temperatures in Europe, and Russian attacks against Ukrainian export facilities.

“India’s export ban needs to be seen in the light of this ominous setting,” said Peter Timmer, Professor Emeritus at Harvard University, who’s studied food security for decades. “There is considerably more reason for concern now that rice prices in Asia could spiral out of control pretty quickly.”

With Vietnam, another major rice shipper, already quoting supplies at $600 a ton for 5% white rice, Thailand may follow that, Chookiat said in an interview. A jump to that level would push Thai prices to the highest since 2012, and compares with the current level of $534 a ton, near a two-year high.

India’s latest restriction, plus an earlier curb on broken rice, affect 30% to 40% of the nation’s total shipments, although Nomura Holdings Inc. warned restrictions could be extended to cover other categories in the event of uneven rainfall and rising domestic inflation. As it stands, the rules could impact flows to China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, and a host of African nations.

Still, outbound shipments could still be permitted on the basis of permission from India to other countries to meet their food-security needs, depending on requests from their governments. In addition, exports of non-basmati parboiled rice and basmati rice are still allowed and that could soften the blow.

The extent to which Asian and African imports will be affected by India’s ban depends on the duration of the prohibition, and the extent to which these countries can arrange purchases through diplomatic channels, said Shirley Mustafa, an economist at the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

Importers could also diversify their origin of their purchases, provided that the export restrictions don’t result in price hikes from these places that could depress demand, especially for price-sensitive buyers, said Mustafa. “This is in fact where the concerns lie,” she said.