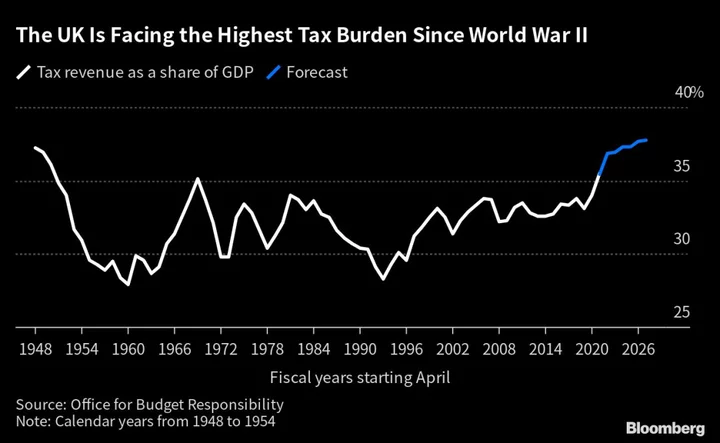

Rising interest rates and gilt yields have punched a £9 billion ($11.3 billion) hole in the UK government finances, jeopardizing both the Conservatives’ plans to cut taxes before the election and the opposition Labour Party’s ambition to spend billions on a green energy transition.

All else equal, the jump in annual borrowing costs would wipe out the headroom against both parties’ main fiscal rule – to get the national debt falling as a share of GDP within five years.

The analysis by Dan Hanson, senior UK economist at Bloomberg Economics, underscores this week’s warning from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development that Britain has “little fiscal space” for giveaways because the public finances are “significantly exposed to movements in interest rates.”

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt met his debt rule in the March budget with just £6.5 billion, or 0.2% of GDP, to spare, the Office for Budget Responsibility estimated at the time.

Even then, the budget watchdog warned that changes in market rates after closing its forecast “would precisely remove the Chancellor’s headroom.” Borrowing costs have since risen further, fueled by bets the Bank of England is not yet done in its battle to tame stubbornly high inflation.

Current market rates would add around £9 billion a year to the cost of servicing the UK’s £2.5 trillion public debt pile relative to the budget forecasts, Hanson calculated. Andrew Goodwin, chief UK economist at Oxford Economics, arrived at a similar figure.

Rates are not the only moving part. Growth has been stronger than expected and energy prices have dropped, which will help the public finances. Inflation has boosted VAT receipts and generated more tax from rising wages, while also pushing up the cost of serving bonds tied to the Retail Prices Index.

However, the analysis is likely to come as a blow to both parties. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s government, trailing far behind Labour in opinion polls, has made little secret of its desire to cut income taxes and extend business tax breaks before an election, due by January 2025 but widely expected to be held next year.

Labour has pledged to spend £28 billion a year on green energy but insists it will do so within its debt rule, which implies other investment will suffer as its has only limited plans to raise tax.

The party hopes to raise £3.2 billion annually by scrapping rules allowing those claiming “non-dom” status to avoid tax on their overseas earnings; £1.6 billion by introducing VAT on private school fees; and £1.1 billion by reversing pension changes criticized as a giveaway to the rich.

Rachel Reeves, who shadows Hunt for the Labour Party, earlier this year dampened speculation it will launch new levies on wealth by saying there were no plans to raise capital gains tax. Labour has proposed extending windfall taxes on North Sea oil producers but that will be harder to justify now energy prices have fallen.

The OECD forecast was overseen by chief economist Clare Lombardelli, who helped prepare Hunt’s budget as the Treasury’s chief economist and only left after the budget in March.