Singapore’s luxury housing deals are drying up as one of the nation’s largest-ever money laundering scandals weighs on the market.

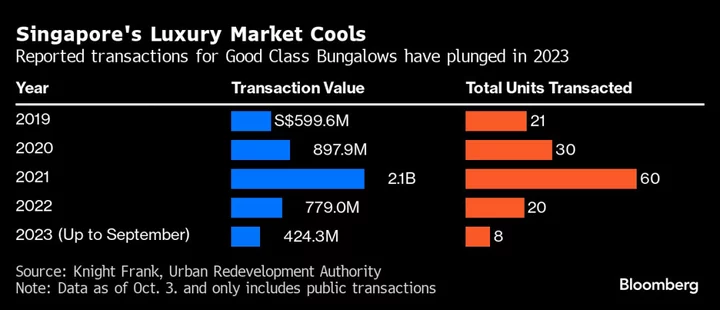

High-end bungalow sales are set for their worst year in nearly a decade with just eight sold as of the end of September, according to data compiled by Knight Frank. Realstar Premier Group Pte — an agency specializing in landed homes — says that for September, it sold fewer than half of the 10 properties it usually brokers a month.

The transaction drought follows money laundering investigations into a group of people of Chinese origin, significant tax hikes on foreign buyers and rising interest rates. Rental demand for mansions that once hit S$150,000 ($110,000) a month has also cooled as the wealthy think twice about flashy homes in the city-state.

“The recent anti-money laundering blitz by the Singapore police force has tainted the luxury property market,” said Lewis Cha, executive director for List Sotheby’s International Realty. “It will take a while for the dust to settle and the market to forget this negative image of luxury real estate.”

Knight Frank figures don’t include undisclosed deals, but the eight mansions sold compare with 20 last year. That’s a fraction of the 60 units transacted in 2021, representing an 80% drop from that year’s S$2.1 billion in sales. Figures that low have not been seen since 2014, when S$431 million worth of such assets were purchased.

Sellers, landlords and agents are turning cautious and employing more rigorous background checks — and in some cases have actively turned down deals from prospective clients.

The owner of a so-called good class bungalow rejected a potential tenant from China’s Fujian province despite the person’s offer to pay for five years of rent upfront on the S$100,000-a-month home, said a person familiar with the matter, asking not to be named discussing private information. Authorities have revealed that most of the suspects arrested in the money laundering case hail from Fujian.

While Singapore’s Council for Estate Agencies advises against placing ads that are discriminatory or stereotyped in nature against any race or group and warns of disciplinary action against property agents who flout the guidelines, there are no laws specifically penalizing landlords for refusing rental on such grounds. The CEA did not respond to a request for comment.

Potential buyers are also “taking a wait-and-see attitude on how the market goes in terms of pricing and the full extent of the investigations and punishment to be meted out,” said Jennifer Chia, a partner at TSMP Law Corp. who heads the firm’s corporate real estate, banking and finance practices.

A reserve for the uber-rich, good class bungalows refer to mansions that have plot sizes of at least 1,400 square meters (15,100 square feet), often situated in the most exclusive neighborhoods. At least half of the 10 arrested took up such dwellings. Among them, Su Baolin stayed in a mansion at Nassim Road, an ultra-exclusive area that’s home to several embassies.

Another accused, Vang Shuiming, lived in a villa with a large rooftop pool and gym, located in a leafy enclave called Bishopsgate near Singapore’s premier shopping belt. Rental data released by the government shows he paid at least S$150,000 a month in November 2020 to live in the property, a record at the time.

After the laundering case, “it’s not easy to find anyone to spend over S$100,000 a month,” said Julian Yip, managing director at Realstar.

Interest rates, rising costs and tax hikes have also curbed buyer interest. Good class bungalows are generally restricted to local buyers — unless the government provides special approval — meaning foreigners often pay exorbitant rents for such property.

“With increased interest rates and uncertainty, buyers have become more circumspect,” said Leonard Tay, head of research at Knight Frank Singapore. “Overall price increases from 2020 have also made it more costly to acquire these luxury landed properties.”

--With assistance from Kevin Varley.