Keir Starmer may well be the next UK prime minister if he can keep opinion polls where they are over the next 18 months. This week he took the knife to one of his Labour Party’s boldest pledges to remake the economy, following months of internal wrangling over whether it was sustainable.

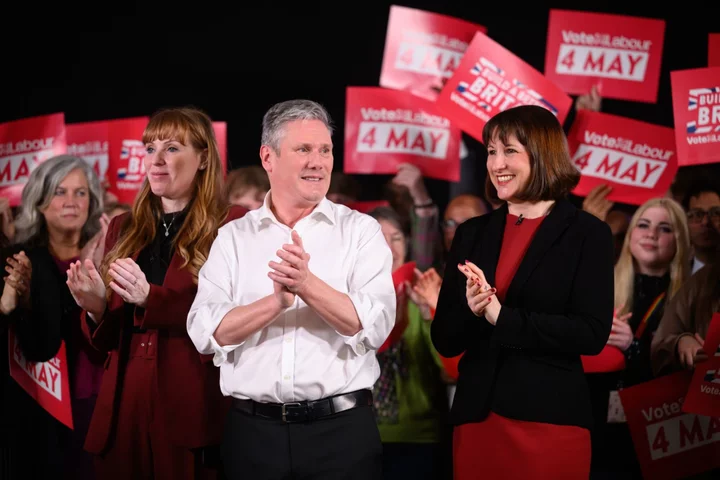

The decision to scale back a plan to invest £140 billion ($176 billion) over five years on a green energy transition, announced Friday by Labour’s shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves, is the type of political gamble Starmer is not known for. When it was first presented in September 2021, both saw it as a defining strategy to make green technology fundamental to growth and put daylight between Labour and the governing Conservatives in the minds of voters.

But the public finances have deteriorated dramatically in the interim, as the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine drove up inflation and the government’s borrowing costs. A Bloomberg analysis found rising interest rates and gilt yields have punched a £9 billion hole in the UK’s coffers — effectively wiping out any headroom against both major parties’ main fiscal rule to get the national debt falling as a share of GDP within five years.

For Starmer and his senior team, the dire economic outlook triggered intense discussions over whether to stick to Labour’s main spending commitment, at times putting the green plan’s architect Ed Miliband — himself a former Labour leader — at odds with senior colleagues, people familiar with the matter said. Those responsible for key departments, such as health and education, feared there would be little money left for them.

Read More: Labour Pushes Back £28 Billion Green Pledge Blaming UK Economy

What emerged Friday was not a full U-Turn: Labour still plans to spend £28 billion a year on its green agenda by the end of its first term, just not every year. Yet the message it sent was clear. Starmer sees the next election being fought on protecting the economy, and he’s not prepared to let his Conservative opponent, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, accuse him of profligacy. The £28 billion number had become an albatross, as one official put it.

Shadow ministers, opposition lawmakers and advisers who spoke on condition of anonymity said the decision is a pivotal moment in Starmer’s pitch for power. Supporters say it shows he and Reeves will do anything to convince voters the economy is safe in their hands, looking to close off a Conservative attack line that Labour means reckless spending and higher taxes.

That fear represents a hangover from Labour’s former left-wing leader Jeremy Corbyn, who led the party to an historic defeat in 2019, as well as the 2008 global financial crisis which the Tories typically link to the then Labour government. Yet the charge of economic mismanagement is much harder for Sunak to emulate, with Britons suffering through a cost-of-living crisis and a record tax burden after 13 years of Conservative rule.

“The one thing they don’t want people to think is they’re splashing the cash with gay abandon,” said Steven Fielding, emeritus professor of politics at Nottingham University. “At the moment they’re seen to be ahead on managing the economy. They don’t want to let that go.”

Reeves made clear Labour intends to try to turn the watered down plan to the party’s advantage, as she blamed the Tories for the deteriorating fiscal position that forced her hand. “I’ll never play fast and loose with the public finances and put people’s mortgages and their pensions in jeopardy in the way the Conservatives have,” she told the BBC.

Meanwhile spokespeople insisted Starmer, Reeves and Miliband are in lockstep and the green transition will be the cornerstone of Labour’s manifesto. It still represents a big dividing line with the Tories, a senior Labour official insisted.

Read More: Rising UK Rates Open £9 Billion Hole in Tory and Labour Plans

Yet some in the party said the question of where it leaves Labour and Starmer is more nuanced. Critics say watering down such a flagship policy risks making Labour look unambitious, while people familiar with the discussions on whether to stick with the £28 billion figure said the wrangling will leave a mark.

Some shadow ministers were frustrated Miliband had secured so much cash so far out from an election, according to one Labour official. Another suggested Miliband had more political nous than less experienced members and that he had taken advantage of a perceived policy vacuum to convince Starmer to commit to the cash. It was naive of Starmer to agree, they said.

Miliband fought hard to defend the policy and spending commitment, people familiar said. A supporter said scaling it back risked exacerbating the view that it’s not clear what Starmer stands for. Labour spokespeople denied any splits.

Another potential knock on Starmer will be how long it took to make the decision. Senior Labour figures, including advisers and lawmakers close to former premier Tony Blair, have been skeptical that the outlay was achievable while keeping to the pledge to tackle the nation’s debt burden.

They warned that the Tories would zero in on the £28 billion figure in an election campaign, and combine it with their own offer of tax cuts in a bid to scare middle-class voters away from Labour and the Liberal Democrats, who would be Labour’s most natural partner in any coalition government.

But the way some Conservatives continued to attack Labour’s scaled back spending plan on Friday illustrates the rationale for the decision, which was made at a series of meetings this week between Starmer, Reeves, Miliband, other key shadow ministers and Labour advisers.

Changing course now, people familiar with their thinking said, will allow Labour to hone its message along the lines of US President Joe Biden’s approach to green tech and economic growth, a theme which Reeves has been promoting in recent weeks with her references to “securonomics” and “Bidenomics.”

Advisers to Starmer and Reeves also want to expand the green investment focus from being mainly on climate change to a more patriotic effort to use energy security to stand up to Russia, and to regenerate pride in industrialized areas by promoting the steel industry and electric car batteries. Starmer will set out the plan later this month, two people familiar with the matter said.

Starmer has been personally irritated by criticism from colleagues that he doesn’t have the killer political instinct necessary to win, one of the people said, adding it’s far harder to argue that now.

--With assistance from Kitty Donaldson and Todd Gillespie.

Author: Alex Wickham, Joe Mayes and Emily Ashton