From the building of a new metro line to buzzing cafes and tavernas and tourists milling around the squares where rioters once clashed with police, Greece’s return from the depths of its economic crisis is impossible to miss in Athens.

The challenge for Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis as he heads into a tight election this weekend is to convince enough Greeks that they aren’t being left behind on that journey from what he calls “old Greece” to the new.

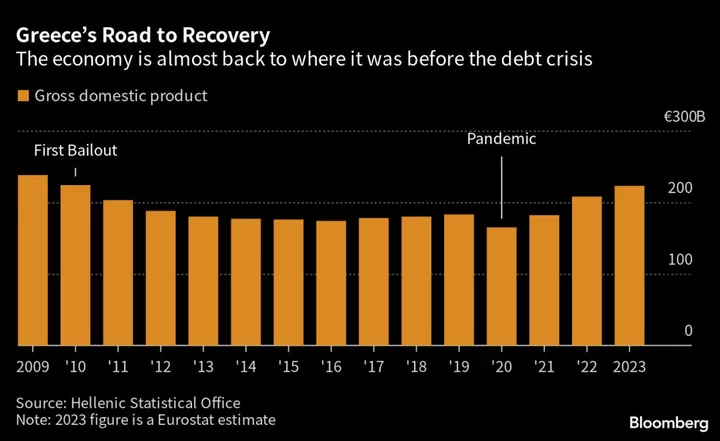

The rebound in the economy has set the nation on track to recover its investment-grade status after 13 years. Gross domestic product is just about where it was when Greece defaulted on its debt in 2010 and it sank by more than a fifth. Unemployment has more than halved from its peak of 28%. Controls to stop the exodus of euros were lifted more than three years ago. Greek stocks and bonds have soared.

But the burden of that recovery is still weighing on an electorate struggling like the rest of the continent. The legacy of the coronavirus pandemic and a cost-of-living crisis driven by food and energy bills is having an outsized effect on households whose income was already squeezed by the years of austerity designed to get Greece back on track.

Mitsotakis and his New Democracy party and rival former premier Alexis Tsipras, whose time in office saw him stand up to those measures ordered by Greece’s creditors until he backed down and secured another bailout, are the main contenders. A change in the electoral system, though, makes a rerun of the vote in the summer highly likely.

Sandwiched between critical votes in Turkey next door, the Greek election may not command the same global attention. Yet at stake is whether Greece can avoid another period of political drama and maintain a trajectory that’s improved its international standing and made the country a place where investors want to do business again.

“The main thing from an outsider’s view point would be that Greece won’t become a crisis point again,” said Nikos Vettas, general director of the Foundation of Economic and Industrial Research in Athens. “In other words, that it will manage to do two things: to service normally its external debt and that it’ll maintain fairly robust growth rates.”

QuicktakeWhy Greece’s Fractured Politics Weigh on Its Recovery

Mitsotakis — whose father served as prime minister in the early 1990s and whose sister was foreign minister in the 2000s — has overseen the next stage of Greece’s transformation, albeit overshadowed by a horrific train crash earlier this year and a spying scandal that implicated his government.

In 2022, Greece managed to reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio faster than any other European country. The risk premium on Greek government bonds compared with Germany’s has fallen by about a third over the past year. They trade with a similar yield to Italian bonds, which hold an investment grade.

Greece’s debt ratio, though, still remains the highest of any in the euro region, while the nation has a way to go to make up for the lost era of its debt crisis.

The economy is expected to reach €223 billion ($243 billion) this year, roughly what it was in 2010, estimates from Eurostat show. Yet per-capita GDP of €21,200 is about 29% less than in the Czech Republic, a country with a similar sized population in Europe’s less affluent former Eastern Bloc. Before the crisis, Greece’s was about 37% higher than that of the Czechs.

The Attica region, which includes the sprawling capital that’s home to more than a third of the country’s 10.6 million people, will ultimately decide who governs Greece.

In the area of Veikou Park in the north of the city, a stadium built for the Olympics in 2004 — Greece’s high water mark — was among those deployed to house asylum seekers in 2015 as the country grappled with a refugee crisis as well as its financial meltdown. Work is now underway on a multibillion-euro metro line that will connect the area with the heart of the Greek capital.

For Ioanna Katrakouli, who works as a cleaner in the park, there’s been no comeback. “You can’t work for so many years while only getting crumbs,” said Katrakouli, 57. Tsipras and his Coalition of the Radical Left, or Syriza, is best placed to make the needed fixes Greece now needs, she said. “They must look at the people, the human being, the average Greek who struggles from morning to night,” she said.

Yiorgos Vafeiadis, 26-year-old gym instructor in the Attica region, remembers well the bad days of the recent past and doesn’t expect “miracles” from any new government. “While a teenager, I can remember capital controls and Tsipras ignoring the result of a referendum he set up on bailout conditions, so for sure I won’t be voting for him,” he said.

Among his circle of peers, the economy is the main issue. He reckons those who earn around €800 a month, just marginally higher than the minimum wage, are planning to vote for Syriza or a smaller party. Those who have a higher monthly salary intend to vote for New Democracy, he said.

Others are keen for Mitsotakis to get re-elected to continue the improvements in the state machine whose unwieldiness defined Greece for decades.

Nafsika Kastana, a 43-year-old veterinarian, likes how the digitalization of government services has made the interaction between citizens and the state easier, she said. “He has managed the economy well, is strong on security and has improved Greece’s image abroad,” said Kastana.

As ever, the main political leaders are trying to convince voters that each of them has the best plan to transport Greece to the future and shed its legacy. The train crash that killed 57 people in February was ultimately blamed on cronyism and chronic underinvestment in the railway system by successive administrations.

Both Mitsotakis and Tsipras have focused on incomes. The incumbent has promised to raise the minimum wage to €950 a month from €780 during the next four-year parliament while his opponent has pledged €880 in his first 50 days in power. In 2010, before the crisis, it was €740.

“Citizens are being asked to decide whether we move forward or return to a past that I think we want to forget,” Mitsotakis, 55, said during a televised debate among all parliamentary party leaders on May 10.

Tsipras, 48, meanwhile, said inequalities mean whole echelons of society are being hollowed out. “If we don’t decide to make big changes, four years from now there won’t be a middle class,” he responded.

But given the metrics of the new voting system — the winner no longer gets 50 bonus seats in the 300-seat parliament to ease its way into power — many Greeks are expected to defect from the two main parties in protest. Should there be another election, expected in July, the rules will change to help produce a clearer result.

What the electorate is looking for is a path to living standards that at least match the average in the euro region, said Vettas at the think tank in Athens.

The politicians in the big parties “are the ones who put us into the bailouts and even now they’re still waving their fingers at us, telling us what to do,” said Yiorgos Krabokoukis, a 65-year-old pensioner sitting in Veikou Park. “Greece has no future with them.”

--With assistance from Aline Oyamada.

(Removes reference to opinion polls in fifth paragraph)