Britain’s steel exports to the European Union risk being hit with a climate surcharge after the government made it cheaper for companies to emit carbon dioxide, potentially erecting another post-Brexit trade barrier with the bloc.

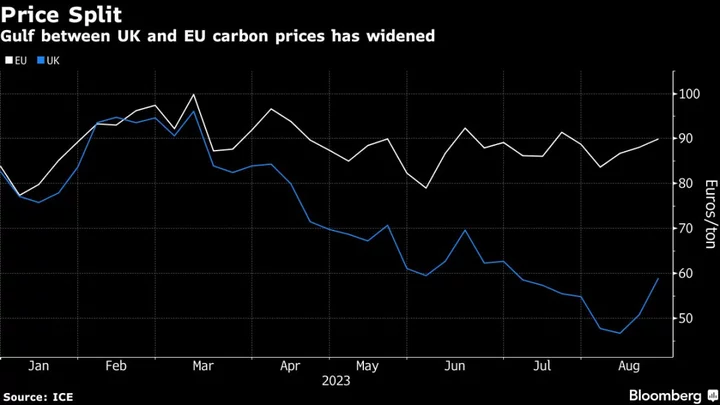

Under the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or CBAM, fees will be added to imports of emissions-intensive goods such as steel and cement from countries deemed to have weaker carbon markets. That may include the UK, whose own pollution rights plunged to an all-time low earlier this month after the government overhauled its emissions trading system.

While such a levy is likely to be relatively small, it’s still a bitter prospect for the UK after having touted the trade benefits that leaving the EU would bring. The CBAM — designed to keep companies from moving to places with looser climate policies — also brings a host of red tape for importers that wouldn’t have been needed if Britain was still a member of the bloc.

“If the main export market of UK steel is the EU, the government might be making a very big mistake,” said Candido Garcia Molyneux, a Brussels-based attorney at the law firm Covington & Burling.

The UK shipped about £5.6 billion ($7.2 billion) of steel to the EU in 2022, or three quarters of its total export volume of the metal.

How EU Will Charge for Emissions Outside Its Borders: QuickTake

BloombergNEF estimates that an EU carbon tariff would rise to about €166 million ($181 million) a year once CBAM is fully implemented, based on a UK carbon price about 20% below the EU’s. It’s currently almost 35% weaker, with UK benchmark emission futures trading at about £49 a ton. Citigroup Inc. said earlier this month the permits may eventually decline toward £22.

The steep drop in UK carbon, which traded on a par with EU permits at the start of the year, comes amid the government’s decision to release about 54 million carbon allowances from 2024 to 2027 — effectively making it less punitive for industry to pollute.

Britain maintains the proposed market reform underpins its net zero emissions goals. Though more allowances will be circulated over the next few years to ease the climate burden on industry, the measure will reduce the total amount of available rights through 2030 by about 30%.

“We want to ensure a smooth transition to the net zero cap allowing the market and participants time to adapt,” a spokesperson for the UK’s Department for Energy Security and Net Zero spokesperson said by email.

The EU is set to phase in the CBAM in 2026 through 2034, but importers will have to begin reporting information about volumes and emissions from October this year. Until recently, the UK didn’t have to worry as its emissions market broadly tracked the EU’s, meaning much of the fee would be waived.

The UK “is not exempted from the CBAM,” a spokesperson for the EU said in response to questions. “Its carbon market is not a part of the EU Emissions Trading System nor is it linked.”

CBAM is still a worry for the steel industry. Importers of British steel will have to show they’re complying with the mechanism, regardless of whether the fee is waived or not.

“If there was a financial barrier as well as an administrative barrier, that would be concerning to us,” said Frank Aaskov, the energy and climate change policy manager at lobby group UK Steel. The fall in carbon prices is “just something that is happening at moment, we don’t know where carbon markets will be in three years time.”

--With assistance from Eddie Spence.