The world’s largest agriculture producers are pushing back against new European Union rules that require proof that crops weren’t grown on deforested land, which producers say will add to the cost of making food.

The latest example of the backlash comes from Brazil, the biggest global exporter of coffee and soybeans. Just this week, the nation’s agriculture minister, Carlos Fávaro, lashed out against the ban, casting doubt on whether it complies with the principles of the World Trade Organization. He added that Brazil is seeking to boost trade with others outside of the EU, including within the five-nation BRICS bloc that also includes Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Brazil is already a steward of the environment, Fávaro said. “If Europe does not want to understand that, there are others that recognize what Brazil does,” he said.

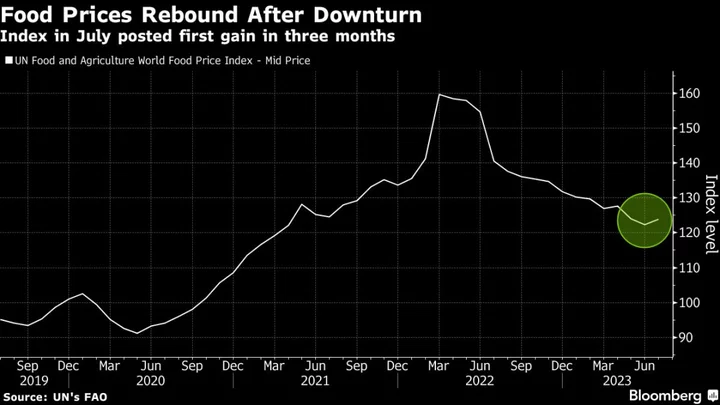

Complying with the new rules will involve implementing full traceability to complex production chains — a task that’s likely to be complicated and expensive. The requirement will apply to a wide range of products, from meat to palm oil, and that will add to agricultural costs at a time when food inflation is once again starting to pick up.

Higher prices won’t just impact buyers in Europe. Since the market is so large, growers will likely need to adopt the new practices quite broadly. Consumers around the globe could end up footing the bill as producers pass on the new costs.

‘Set the Bar High’

Even as producers are decrying the rules, companies and farmers around the world are already taking steps to adjust to them and make sure they have continued access to the important European markets.

Major trading companies will need to adjust their procedures all around the globe, said Paulo Sousa, the head of operations in Brazil for Cargill Inc., one of the world’s top agricultural companies.

Meeting the rules will bring additional costs, but it also “brings us the certainty that customers will be served,” he said. “We have to set the bar high.”

The rules are intended to help fight climate change and biodiversity loss, according a spokesperson from the European Commission. The regulation applies “to commodities, not countries and is neither punitive nor protectionist, but creates a level playing field,” the spokesperson said, adding that the requirements were designed to be WTO compliant.

The deforestation legislation that came into force on June 29 gives suppliers 18 to 24 months to adjust. That’s not much time when taking into account the varying levels of traceability in place now. There’s concern that the time line and rules will end up favoring those in more developed regions that already have more advanced technologies and practices in place, while leaving smaller, more vulnerable producers behind.

“Who is going to pay for this? It cannot be the producers,” said Vanusia Nogueira, the president of the International Coffee Organization.

Cocoa Prices

Ivory Coast and Ghana, which together account for about two-thirds of global output of cocoa, are studying a new pricing mechanism to account for the added costs. That would be in addition to the so-called Living-Income Differential, a surcharge of $400 per ton that was implemented to improve farmer pay.

“You can’t add to the production cost without reflecting that in the price,” said Yves Kone, who heads Conseil Cafe-Cacao, Ivory Coast’s cocoa regulator.

It’s a similar story for beef. The legislation requires tracking all cattle from its birthplace, a challenge for top exporter Brazil, where an animal lives in different places over the many phases of its life.

Since 2009, shipments to Europe have already been controlled by a specific system that requires individual animal tracking. But now there’s the need to expand the mechanism from the current 90 days of tracking prior to slaughter to a much longer period that starts from the animal’s birth, said Fernando Sampaio, an executive at industry group Abiec.

“We’ll work with farms that are approved and bring their suppliers into the system, but Europeans are aware that costs will be passed ahead to importers,” he said.

In Vietnam, the world’s second-biggest coffee exporter, beans are grown mainly by small-household farms. A great number of the farms are smaller than 0.5 hectares (1.2 acres), according to the coffee association.

“It’s tough to trace products’ origin to the exact location of each farm,” said Nguyen Nam Hai, the chair of Vietnam Coffee Cocoa Association.

--With assistance from Yinka Ibukun and John Ainger.

Author: Dayanne Sousa, Anuradha Raghu and Mai Ngoc Chau