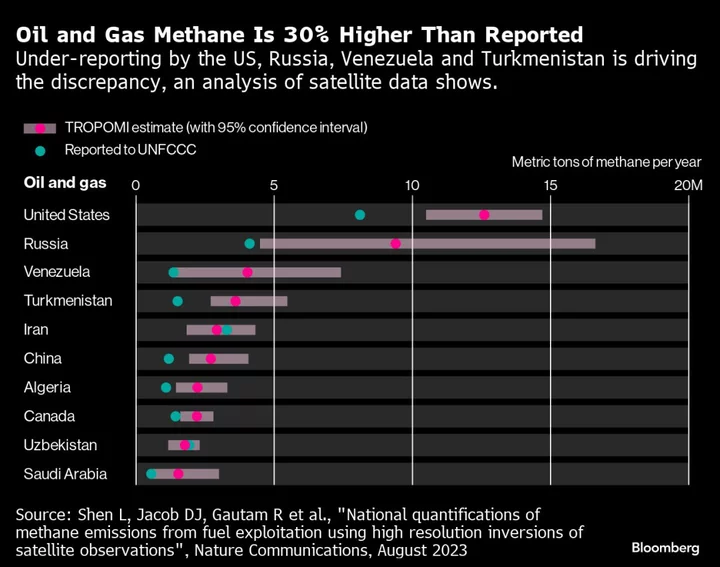

China’s reliance on coal — and how to reduce it — was a key topic of discussion at an international group this week as nations work to solve one of the thornier global climate issues, Canadian Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault said.

China uses more coal for electricity generation than all other countries combined and is allowing construction of a fleet of new plants fired by the fuel. In an interview, Guilbeault acknowledged that the nation’s policies to cut dependence on coal are still in development.

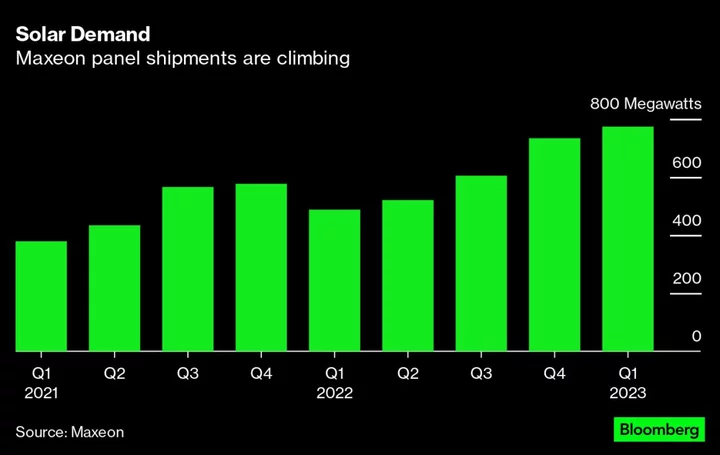

“We understand that the way they can reduce their dependency on coal is obviously through more renewables, storage efficiency,” Guilbeault said by phone from China, where he attended this week’s meeting of the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development.

“But the purpose of the work we will be doing next year is exploring specifically what does that mean?” Guilbeault added. “What does that concretely look like?” He’s vice chair of the council, a body founded in 1992 with support from Canada, which has been its biggest international donor.

Canada has been reducing its coal-fired electricity, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has pledged to end thermal coal exports by 2030. In the meantime, Canada exported C$7.7 billion ($5.7 billion) of coal in 2021, according to government statistics that also include metallurgical coal for steel production. Nearly half of Canada’s coal exports go to China.

Read More: China’s Coal Build-Out Raises Questions on Future Power Plans

Asked whether he sees Canadian natural gas helping China transition away from coal, Guilbeault said Canada will have multiple LNG terminals coming online on its west coast in the next few years. But he also sounded a cautionary note.

“Governments won’t decide where where the LNG goes, the markets will,” he said. “We want to be mindful of the role that LNG can play, but in the long term, we also need to reduce our dependency on all fossil fuels, and that includes LNG.”

Guilbeault’s trip this week created significant controversy at home due to a series of diplomatic crises between Canada and China.

The biggest conflict began in 2018 after Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s chief financial officer, was arrested in Vancouver on a US extradition request. Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor were detained within days of Meng’s arrest and held until all three were freed in September 2021.

More recently, Trudeau’s government has been under fire for how it responded to intelligence reports that China has interfered in Canadian elections in an attempt to elect Beijing-friendly politicians. Trudeau is widely expected to call a judicial inquiry into the matter in the coming weeks.

Still, Guilbeault defended his role with the council. He pointed out that while Canada’s Indo-Pacific strategy — which was published last year — aims to counter Chinese influence in the region, it also promises to work with China on climate policy. Western allies including the US and UK also have been engaging with China on climate change.

The council has experts and government representatives from all over the world, and international involvement makes it easier to debate “sensitive” topics such as coal consumption, he said.

“It’s a more neutral forum where we can talk about these things and it’s not as controversial, it makes it less politically sensitive,” he said.