On the surface, Ford Motor Co. would seem an unlikely party to be on the receiving end of the largest loan that an office within the US Department of Energy has ever doled out.

Just last month, the automaker touted the almost $29 billion of cash on its balance sheet and the more than $46 billion worth of total liquidity at its disposal. The Energy Department nevertheless added to that on Thursday, announcing a loan of as much as $9.2 billion to BlueOval SK, a venture constructing three plants that will produce batteries for Ford’s future electric vehicles.

So how did we get here — where one of the largest corporate borrowers in the US went to the government for so much money, instead of the private sector?

Consider two factors: The vast amount of money Ford is going to be spending in the coming years to go electric, and the skepticism of some on Wall Street that all this will go smoothly.

Ford told investors early last year that it would plow $50 billion into its EV-making efforts by 2026, an enormous sum even for a company its size. When Ford hosted its capital markets day last month, Morgan Stanley analyst Adam Jonas posited that many in the room believe that taking on Tesla Inc. and the Chinese carmakers that have dominated the early electric age amounts to “a pretty easy way to destroy billions and billions of capital.”

“Has the management team and the family considered funding the EV investments in any other way?” Jonas asked.

“Not as of yet,” Ford Chief Executive Officer Jim Farley replied. While he said management was “really confident about our approach,” the line of questioning spoke to the apprehension of some investors about the risks involved in trying to revolutionize a 120-year-old company.

Ford is expecting its EV business to lose $3 billion this year, with much of that deficit having to do with its investment toward a planned 15-fold production increase in very short order. By the end of 2026, the company wants to be able to make 2 million EVs a year.

The Energy Department’s loan will cover much of that near-term expense. It may cover close to the entire battery plant portion of the $11.4 billion that Ford and its joint venture partner SK On have said they’ll spend on three cell factories and one pickup assembly in Kentucky and Tennessee, since the truck facility included within that total isn’t a recipient of the loan.

While neither Ford nor the Energy Department divulged details on the terms of the loan, both have at least offered hints.

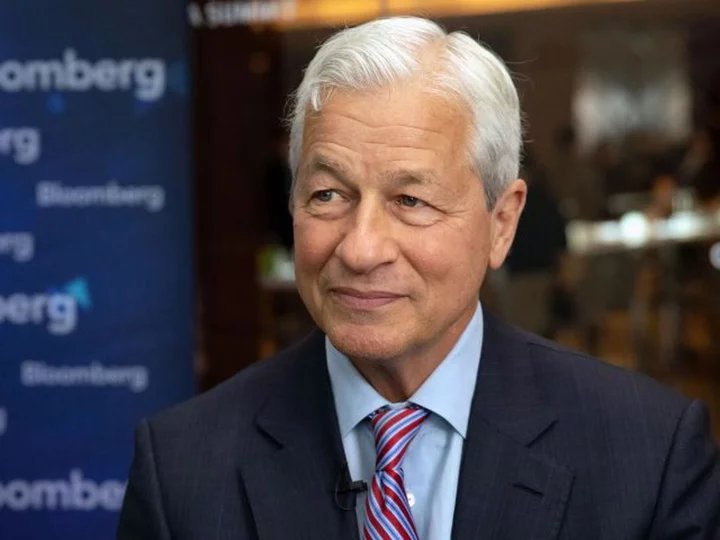

“You can imagine if they did it purely on Wall Street, without using our program, the terms may have been quite a bit less favorable,” Jigar Shah, the director of the Energy Department’s Loan Programs Office, told Bloomberg Green’s Zero podcast.

When reporting quarterly earnings in October of last year, Ford mentioned that “low-cost” Energy Department loans were among the many potential benefits of the just-passed Inflation Reduction Act.

If history is any guide, Ford and SK On will have plenty of time to settle up with the government. Ford borrowed $5.9 billion from the same loan program in 2009 and paid it off in 2022 — 13 years later.

Winning over Wall Street may be a tougher task. Two days of driving, dining and discussion at its Dearborn, Michigan, headquarters last month wasn’t enough to sway some skeptics.

“For a lot of years, Ford has disappointed,” said David Whiston, an analyst with Morningstar. To achieve its EV goals, “there’s a massive amount of improvement that needs to come, particularly from volume. That’s where the skepticism comes from.”