Blood, guts and cheap cuts: We need an alternative to eating animals – and ‘ethical meat’ isn’t the answer

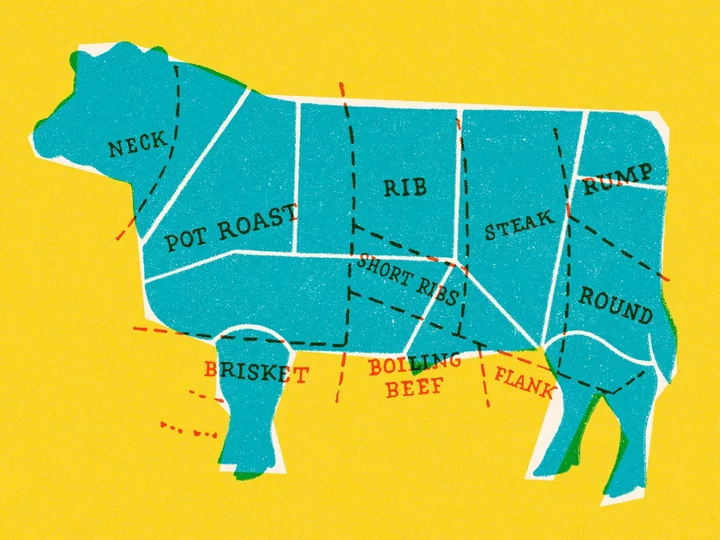

Amber Husain was cooking dinner for a friend when she suddenly realised the meat she was preparing was a corpse. She looked at the chicken in front of her and was overcome with a visceral sense of disgust. Instead of food, she saw “a carcass – plucked, beheaded, and fleshy”. Husain was 26 when she had this epiphany, and it served as a wake-up call not just for her stomach but her mind, too – as her personal tastes shifted away from meat products, her political outlook on the meat industry and food production more broadly also altered and expanded. Five years later, that moment of revulsion forms the opening of her new book, Meat Love, in which she scrutinises the idea of “ethical” meat consumption, and dares to ask how the contemporary middle classes have come to criticise “the worst violence against animals” while still happily feeding on their flesh. Why, for example, has well-heeled, middle-class London gone nuts for slurping bone marrow from the shin bones of baby cows? Why is offal on so many trendy menus? How has contemporary culture at large come to accept that factory farms are monstrous, but that if animals are cared for, cherished and loved while alive, we should feel better about killing them for our carnivorous pleasures? “For ages, I was one of those carnivores who felt mildly bad about eating meat but just turned that into this inane, self-consciously sadistic part of the pleasure of it all,” Husein tells me. “The more my diet started to revolve around stuff that wasn’t meat, the weirder meat started to feel. Interestingly, once my stomach had been radicalised, I found I had a much greater intellectual openness to thinking about the politics of meat.” Having freed herself from the conflict of eating meat but also feeling bad about it, she found she was able to go beyond those questions of morality – which she suggests can be “stifling” – and think politically. “Now that I have no desire to eat animals, there’s nothing to stop me reckoning with what it means that the meat industry [consists of] an underclass of both humans and animals who are exploited and – in the animals’ case – killed for pleasure and profit.” This is the essential crux of Husain’s argument, and it’s something often lacking in discussions around the “ethics” of meat consumption. For Husain, the question is not, “how can humans eat meat responsibly?” but “how are certain lives devalued to an extent that their suffering can be written off, in order to ‘make a killing’?” What she’s saying, in other words, is that whether the meat on the table has come from a factory farm or an organic farm, or whether you’re tucking in at Burger King or the River Cafe, the path to the plate is still paved with violence. And, while current cultural trends may claim it is better to love and respect an animal before killing and consuming it, perhaps what this cultivates is the ability to embrace exploitation “in a spirit of virtuous indulgence”. What does it really mean, for all living beings, if love is imagined as compatible with killing? “To slide your buttery hand between the flesh and skin of a thing that, if only for a moment, you have re-learnt to perceive as a corpse, is to give an invigorating massage to your sense of political possibility,” Husain writes in Meat Love. By the slim book’s end, her invigorated “sense of political possibility” has led to “a ravenous hunger – a desire for a different culture, a different society”; a new world “in which no one, neither animal, immigrant, worker, woman, or peasant, was considered a thing to be owned, controlled, killed, or left to die”. For many, the leap from a chicken breast on a plate to the exploitation of oppressed people around the globe might seem like a vast one. Yet, it certainly seems clear that there has been a marked shift in the way meat is conceived and consumed – among the middle classes, at least. Since the turn of the millennium, foodie figures like Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall have been promoting “seasonal, ethically produced food” as part of a broader commitment to caring for the environment. At the same time, a distinctly carnivorous spirit has taken hold – one that professes to be an “honest”, “grounded” and “down to earth” ethos. “Good food, good eating, is all about blood and organs, cruelty and decay,” Anthony Bourdain wrote at the start of the 1999 New Yorker article that would, eventually, catapult him into global foodie fame. I find it easy to laugh at Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall and people like that, but I’m not totally convinced that they’re really the bad guys Lewis Bassett Then there’s Fergus Henderson and St John – the illustrious London restaurant, born in 1994 on the premises of a former bacon smokehouse, which popularised “nose to tail” dining. This offal-centric “no waste” approach is neatly summed up in Henderson’s oft-quoted phrase: “If you’re going to kill the animal, it seems only polite to use the whole thing.” Traditionally “cheap cuts” are “elevated” from a source of sustenance for the working classes, to a source of virtue for the urban bourgeois. According to its own cookbook, St John dishes combine “high sophistication with peasant roughness” – that winning aesthetic formula that also sees middle-class urbanites flocking to farmers’ markets and chugging natural wine. In a sharp and searing piece for food and culture newsletter Vittles, writer Sheena Patel dubs this “Rich Person Peasantcore”, asking: “Why are these influencers pretending that they themselves till the land and eat like 17th-century French peasants when in fact their chopping boards cost more than most people’s rent?” In the face of swathes of small plates adorned with offal, and slices of ham served for upwards of £20, it seems like a pertinent question not just for influencers, but also for today’s trendiest restaurateurs and diners. Lewis Bassett is a chef and the host of The Full English podcast, which, over its two seasons, has dived into everything from the birth of “modern European” cuisine to high food prices, factory farms, and why Britain is in love with Greggs. “It’s interesting the way we create these fantastical worlds for us to eat within,” he says. “It is clearly a fantasy to imagine that you can have the rural experience of a peasant in France or Italy, in modern-day Britain.” Yet, he also says that this trend is far from new. The current “rustic” style – typified by “nose to tail eating” – is, he suggests, “intimately tied with what you could call a culinary and broader cultural movement that appears in the wake of countercultural movements in the Sixties, and eventually finds its way into food, especially as some of those countercultural people get a bit older and a bit more affluence”. Essentially, “it’s the same thing that manifested in places like Habitat,” he says, of the homewares and furnishings brand founded in 1964 by Terence Conran. Both design and dining were transformed, offering experiences to the middle classes that were both refined and casual at the same time. Alongside that cultural shift, and “that fashion for pared-down forms of eating out”, Bassett notes the arrival of a broader awareness of environmental and animal welfare concerns. “It’s obviously easy to ridicule these middle-class forms of culture,” he says, “but these concerns are ones I certainly share and I think should be considerations for everyone. I find it easy to laugh at Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall and people like that, but I’m not totally convinced that they’re really the bad guys.” So is there a danger that legitimate backlash to the “thrifty rural”, “nose to tail” trend – and bourgeois “peasantcore” more broadly – could spill over into an attack on all food industry attempts at sustainability? “I think people don’t want stuffy fine dining experiences,” Bassett says, “but at the same time, having the kind of pared-down, rustic, ‘peasant food’ – like, having ham served to you at St John costs you 20 quid – maybe people are slightly sick of that.” He quickly adds, though, that he is “not saying it can come any cheaper than 20 quid, because when you spend a lot of time and effort rearing animals properly, and paying chefs properly, and paying rents in your restaurants, that racks up”. It seems there is a tension, then, between practical and immediate ethical matters – such as paying food industry staff liveable wages or reducing food waste – and broader questions about what kind of society we wish to live in or create. Is the question of “ethical” meat consumption, as Husain suggested, “beyond morality” – a question of politics only? Or is it still, at heart, a moral dilemma, based on people’s personal sense of “right” and “wrong”? Summing up Husain’s attitude towards animals in Meat Love, Bassett suggests “she’s saying that, if you love them so much, why are you killing them? I suppose where Amber Husain and I would slightly disagree is that I’m not convinced that killing an animal is inherently wrong.” Away from the carnal appreciation and “peasantcore” of contemporary restaurant culture, meat-eating often seems to be conceived as either a “guilty pleasure” or a “grim necessity”. In all these cases, however, there appears to be an overriding sense that there is “no alternative” to a meat-eating status quo. The late cultural critic Mark Fisher famously used similar terms to define “capitalist realism”, meaning that capitalism is the only viable economic system, and thus there can be no imaginable alternative. Is it possible we’re also stuck in a kind of “carnivorous realism”? If so, it might be because the two are so interlinked. As Husain puts it, “meat is the inevitable outcome of an economic system that relies on cheap labour and cheap life. But that doesn’t mean meat is a necessity, it means a new economic order is a necessity.” Perhaps taking the leap from a vegetarian diet to full-scale social and economic revolution still seems unthinkable to many. But, in nasty, brutish and austere times, it has also perhaps never been more necessary to seriously consider who can eat, and who is made meat. “I think we need an avalanche of political will from within the food justice, land justice, climate justice and labour movements to radically transform society,” Husain says. With that as the goal, she believes it isn’t helpful “for us to be clinging to the idea of meat as a pleasure”: “If we can’t imagine something other than animal flesh to eat for dinner we might struggle to imagine an entirely different society.” ‘Meat Love: An Ideology of the Flesh’ by Amber Husain is out now Read More Between Brexit and Covid, London’s food scene has become a dog’s dinner – can it be saved? It’s time for booze bottles to have health warning labels Should I give up Diet Coke? With aspartame under suspicion, an addict speaks Food portion sizes on packaging are ‘unrealistic and confusing’, says Which? In Horto: Hearty, outdoorsy fare in a secret London Bridge garden Zero-fuss cooking: BBQ pork ribs and zingy Asian slaw

1970-01-01 08:00

Arda Guler sent home from Real Madrid pre-season tour with knee injury

Real Madrid attacking midfielder Arda Guler has been sent home from their pre-season tour of the United States due to a knee injury.

1970-01-01 08:00

Uber self-driving car test driver pleads guilty to endangerment in pedestrian death case

The Uber test driver behind the wheel of one of the company's self-driving cars, when it hit and killed a pedestrian in 2018, pleaded guilty to endangerment and was sentenced to three years of supervised probation Friday, according to officials.

1970-01-01 08:00

Vinicius Junior heaps praise on 'idol' Cristiano Ronaldo

Vinicius Junior explains why he idolises Cristiano Ronaldo after taking his Real Madrid shirt number.

1970-01-01 08:00

How Real Madrid plan to exploit loophole to register Jude Bellingham as EU player

Jude Bellingham is set to receive an Irish passport in order to be registered as an EU player at Real Madrid.

1970-01-01 08:00

Kenya cyber-attack: Why is eCitizen down?

A key government online platform has been down for several days and mobile money services are also affected.

1970-01-01 08:00

Food portion sizes on packaging are ‘unrealistic and confusing’, says Which?

Portion information on food packaging is too “confusing, inconsistent or unrealistic” for people to get a clear understanding of how much sugar, fat and salt they are consuming, according to new research. Which? surveyed more than 1,200 people on portion sizes and found that a large number of people could not estimate correctly how many servings popular supermarket foods contained. The consumer champion found that respondents often assumed portions were larger than the suggested serving sizes listed on the packaging, and labelled the latter “small” and “unrealistic”. For example, more than half of respondents thought a 225g pack of halloumi would cover two to four servings, but the package information suggests it should feed seven. More than a third of respondents thought a tub of Pringles contained two to four portions, but the packaging suggests it contains six to seven servings of around 13 crisps per person. The majority (79 per cent) of those who took part in the survey thought a supermarket meal deal was designed to serve one person, given they are typically purchased for a single person’s meal. However, Which? pointed out that while the sandwich is usually for one person, the drink and snack that are usually included in the deal may be designed for two. The research also found inconsistencies in portion sizes across pack sizes for popular products. Walkers Ready Salted Crisps come in three different individual pack sizes ranging from 25g per pack in a multipack to 45g in a grab bag, but these all count as one portion. Meanwhile, a 150g sharing bag suggests that a single portion is 30g. Other products that have similar inconsistencies include Cadbury’s Dairy Milk, which have recommended serving sizes ranging from 20g to 33.5g. Which? also found inconsistencies in serving size suggestions depending on the brand, even if the amount of product in a package is similar. A 300g back of Dell Ugo tomato and mozzarella tortellini states that it serves two people, but a near-identical version by Marks & Spencer that also weighs 300g says it contains three servings. Respondents also found it difficult to estimate an appropriate portion size for drinks, it was revealed, after 229 people were asked to pour themselves a glass of wine, juice or smoothie and measure how much they served themselves. Just under half (49 per cent) of white wine drinkers poured themselves more than the recommended 125ml, with the largest pour recorded rising to more than double that (275ml). Among red wine drinkers, almost two thirds (69 per cent) poured a much larger portion, which the largest pour reaching 250ml. More than half (54 per cent) of those who drank orange juice served themselves more than the recommended 150ml, with the largest pour measuring in at 400ml. Orange juice packages show the amount of calories and sugar in a 150ml serving, which is around 62 calories and 13g of sugar. However, a 400ml glass has 166 calories and 35g of sugar, more free sugar than an adult should have in a day according to the NHS. Which? said: “Although traffic light labelling is a useful guide to the nutritional value, for it to be effective it must be based on realistic portion sizes. Manufacturers and supermarkets should look to make improvements and provide clearer labelling on serving sizes so shoppers are not misled about the food they buy.” Customers are also advised to check packaging and to measure portion sizes at home to get a clearer idea of what they should consume looks like according to the packaging suggestions. Shefalee Loth, a nutritionist at Which?, said: “Which? found people can be confused by inconsistent and unrealistic serving sizes and that the way that manufacturers provide these can sometimes make it difficult to assess just how healthy a product is. “Nutrition labelling is really valuable for consumers, including front of pack traffic light labelling, but it needs to be based on meaningful and consistent portion sizes.” Read More Men have a problem – and it won’t be solved by either Andrew Tate or Caitlin Moran Elon Musk reacts to ex-wife Talulah Riley’s engagement to Thomas Brodie-Sangster Thomas Brodie-Sangster references Love Actually in sweet engagement announcement with Talulah Riley In Horto: Hearty, outdoorsy fare in a secret London Bridge garden Zero-fuss cooking: BBQ pork ribs and zingy Asian slaw Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie ‘set to try and resolve’ longrunning vineyard dispute

1970-01-01 08:00

In Horto: Hearty, outdoorsy fare in a secret London Bridge garden

Walking into In Horto feels like walking into someone’s garden after the green thumbed designers of Your Garden Made Perfect have had their way with it. Stylish yet homely, with thought put into making every corner feel like you’re stepping into someone’s al fresco dinner party – hexagonal red brick flooring, rattan lamp shades and roof, wooden dining tables and chairs, as well as rustic dishes and serving plates. Potted plants welcome you at the entrance and vines twirl around the edges of the restaurant, which gives it an even more cloistered feeling. Just a five minute walk from London Bridge, right next to Flat Iron Square, In Horto has a distinctly different vibe to its packed surroundings. There’s the Borough Market crowd, where inching behind tourists is only made worth it if you procure a sausage roll from the Ginger Pig (mmm, dreamy); while Flat Iron Square boasts a hipper, boozier clientele. In Horto offers a bit of an oasis from both – a quieter, calmer place to sit down and have a meal. In Horto is a venture by TVG Hospitality, also known as The Venue Group, which boasts Mumford and Sons member Ben Lovett as one of its backers. The group also operates Flat Iron Square, which it moved from its original location on the corner of Southwark Bridge Road and Union Street to its current home last year. So it makes sense that the company is trying to develop the area by providing more restaurants with different concepts – it also opened Carrubo next to In Horto, a Mediterranean-inspired “light bites” place. The clue to why the restaurant feels so much like a garden party is in the name; In Horto in Latin is “in the garden”. The cooking on display here is very much focused on outdoorsy, wood-fired cooking, with a beautiful large domed oven taking pride of place behind the counter. Almost every dish is baked, roasted or grilled in this hard-working piece of equipment, bar things like the charcuterie board or the burrata and caponata, but even that has a touch of fire with the addition of smoked white balsamic dressing. In Horto’s menu moves with the seasons, but some things that are a staple and absolutely worth having again and again. The confit potato chips, which have been described as an “uncanny” dupe of Quality Chop House’s own version, are very, very good – layers of nearly paper thin potatoes layered and cooked in a thick wedge, before being portioned into chunky batons and roasted so that they caramelise and crisp up on the outside, but retain a delicious softness on the inside. The heritage beetroot with vegan feta and sunflower and pumpkin seeds also went down a treat, with the earthy, gorgeously red and purple root vegetables allowed to shine. We were big fans of the ’nduja butter and burnt onion butter that can be ordered and slathered with relish on bread. Also enjoyed were tenderly shredded venison batons ensconced in crispy crumbs, and while I generally find padron peppers to be a bit… well, boring, In Horto’s were covered in a healthy sprinkling of Aleppo salt that gave the soft, slightly charred vegetables that much-needed crunch. The mains were hearty and great for sharing, although perhaps less exciting than the starters and sides. There’s only so many roasted vegetables you can eat before it starts to taste a little monotonous. Having said that, the slow roasted braised lamb was a triumph; tender and juicy, with a delicious amount of fat that melts on the tongue. The real joy of In Horto’s menu is that it is all made to be shared, which I love. There is something so comforting and communal about passing dishes to one another, making sure everyone tries a little bit of everything. After all that food, it’d make sense that there was little room for dessert. Except I’m nothing if not determined. We had to be sensible though – the tarte tatin with vanilla ice cream sounded bloody lovely, but would have been far too much and we would have had to be rolled home. Being the balanced and rational eaters we are, we opted to share the rich, luxurious chocolate mousse with honeycomb and salted caramel ice cream. Unwise? Perhaps, just a little. But I have no regrets. In Horto, 53b Southwark St, London, SE1 1RU | inhorto.co.uk | 020 3179 2909 Read More The Union Rye, review: Finally, a decent restaurant in this charming East Sussex town Forest Side: Heavenly Cumbrian produce elevated to Michelin-starred proportions I tried the food at Idris Elba’s restaurant – he should stick to wine

1970-01-01 08:00

Six players Real Madrid gave up on and sold too soon

Six players, including Arjen Robben and Mesur Ozil, that could have offered more to Real Madrid were they given the chance to stay at the club longer.

1970-01-01 08:00

Toni Kroos heaps praise on Real Madrid teenage starlet

Real Madrid midfielder Toni Kroos has showered the summer signing Arda Guler with praise for his start to life in Spain on and off the pitch.

1970-01-01 08:00

Chick-fil-A wants to send your drive-thru chicken on a conveyor belt and down a chute

Chick-fil-A is testing out two new restaurant concepts — a four-lane drive thru with a kitchen above and a walk-up store for digital orders — as it becomes the latest chain to try to get customers to skip the dining room.

1970-01-01 08:00

MLB Rumors: Eduardo Rodriguez race, Angels money quote, Dylan Cease

MLB Rumors: Are the White Sox taking calls on Dylan Cease?Dylan Cease isn't going anywhere.Yes, the Chicago White Sox are open for business, selling at the MLB trade deadline with an eye towards competing in 2024. But, they view Cease as part of that competitive plan.Cease is a former...

1970-01-01 08:00